|

Posted 11/23/20

FIX THOSE NEIGHBORHOODS!

Creating safe places calls for a comprehensive, organic approach

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. While campaigning in Charlotte four years ago, candidate Trump promised that he would place the nation’s impoverished communities on the path to prosperity with major investments in infrastructure, job development and education. He would also fight the disorder that bedevils poor areas and assure that justice was dispensed equally to all. While some Black voices were skeptical about the sincerity of Trump’s “New Deal for Black America,” others applauded his apparent enthusiasm for reform. Even after eight years of Democratic rule, poverty and crime still beset the inner cities. So give him a chance!

And for a single term, America did. According to the Fed’s most recent (2019) survey, the economy performed well, with the gross domestic product going up unemployment going down. And until the ravages of the pandemic and urban disorder, violence was also on the way down. According to FBI figures, the violent crime rate dropped one percent during 2018-2019 and property crime fell four and one-half percent.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

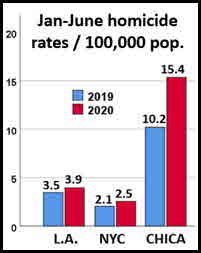

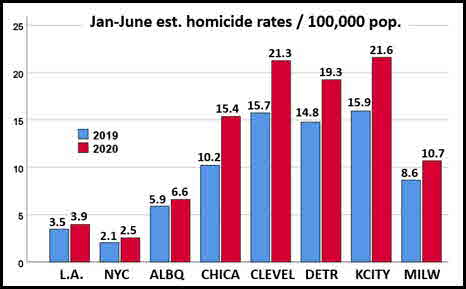

Yet not everyone benefited. As the Fed noted, income distribution has hardly budged in the last three decades, with the top one-third enjoying about a third of the nation’s wealth while the bottom half seems consigned to a measly two percent. Federal crime statistics demonstrate marked disparities as to place. Detroit closed out 2015 with 295 murders; New York City had 319. Once their populations are taken into account, the Motor City’s homicide rate – 43.8 per 100,000 pop. – was more than ten times the Big Apple’s measly 4.1. Four years later the results proved much the same, with Detroit’s 492 murders yielding a 41.4 rate while New York City’s 319 homicides delivered a far gentler 3.8, even better than the nation’s 5.0.

Considering New York City’s seemingly benign crime numbers it seems to make perfect sense that Mayor Bill de Blasio calls it the “safest big city in America.” Only problem is, “New York City” is a place name. People live, work and play in neighborhoods. And during a career fighting crime, and another trying to figure out where it comes from, your blogger discovered that focusing on tangible places can prove illuminating in ways that yakking about wholes obscures.

Politicians know that. Mayor de Blasio counts on a profusion of prosperous neighborhoods to produce low citywide crime numbers. Consider the Upper East Side. With a population of 220,000 and a poverty rate of only 7.2 percent (versus the city’s twenty), its police precinct, the 19th., posted zero murders in 2017, one in 2018, and zero again in 2019. And while 2020 has supposedly brought everyone major grief crime-wise, as of November 15 the 19th. has recorded just one killing.

Contrast that with the Big Apple’s downtrodden Brownsville district. Burdened with a 29.4 percent poverty rate, its 86,000 residents have historically endured an abysmal level of violence. Brownsville’s police precinct, the 73rd., logged nine murders in 2017, thirteen in 2018 and eleven in 2019. That produced a murder rate (per 100,000 pop.) more than three times New York City’s overall rate and about thirteen times that of the Upper East Side. Then consider what happened this year. As of November 15 the poverty-stricken 73rd. logged an astounding 25 murders, more than twice its merely deplorable 2019 figure.

Upper East Siders managed to shake off the pandemic and George Floyd. Clearly not the Brownsvillians. Note to Hizzoner: they’re both your denizens.

Switch shores. Los Angeles Police Department’s West Los Angeles station serves an affluent area of 228,000 inhabitants. Its primary ZIP, 90025, boasts a poverty rate of 11.25 percent. West L.A. Division reported two murders between January 1 and November 14, 2018, one between those dates in 2019, and four this year. In comparison, the 77th. Street station tends to a score of impoverished neighborhoods. Its primary Zip code, 90003, suffers from a poverty rate of 30.7 percent. Although the 77th. serves a substantially smaller population of about 175,000, it endured far, far more murders (39, 35 and 48) than West L.A. Division during the same periods. And while murder did increase in both areas between 2019 and 2020, check out the leap in the 77th.

Indeed, things in the poor parts of L.A. have deteriorated so markedly this year that four killings last night in South Los Angeles caused the city to reach that 300-murder milestone it successfully avoided for a decade. Shades of Brownsville!

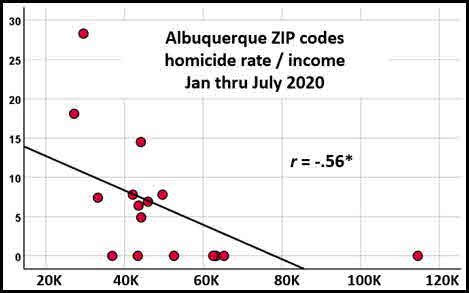

So, crime-wise, is there really a “New York City”? An “L.A.”? During the last decade posts in our “Neighborhoods” special section reported similar disparities within cities across the U.S. For example, consider Minneapolis, that usually tranquil place where the death at the hands of police of Mr. George Floyd set off national waves of protest that have yet to subside. Coding its eighty-five neighborhoods for violent crimes per 100,000 pop., we recently compared the four least violent (mean rate 0.7) with the four most brutish (mean rate 35.6). That exposed a huge disparity in mean family income: $106,347 for the calm areas, $45,678 in the not-so-peaceful.

So is there only one Minneapolis? No more so than one Portland! Our national capital of dissent has at least 87 neighborhoods. Comparing the ten neighborhoods with the lowest violence rates (mean=1.5) against the ten with the highest (mean=9.0) revealed that only nine percent of the former were in poverty versus 21.4 percent of the latter. Ditto Baltimore, South Bend, Chicago and elsewhere. (Click here, here and here.)

It’s hardly a secret that poverty and violence are locked in an embrace. Years ago your blogger and his ATF colleagues discreetly trailed along as traffickers hauled freshly-bought handguns into distressed neighborhoods for resale to local peddlers. Alas, a gun from one of the loads we missed was used to murder a police officer. That tragedy, which haunts me to this day, furnished the inspiration for “Sources of Crime Guns in Los Angeles, California,” a journal article I wrote while transitioning into academia.

When yours truly arrived on campus he discovered that the criminal justice educational community was not much interested in neighborhoods. That lack of attention has apparently continued. But ignoring place can easily lead us astray. A recent study of Chicago’s move to facilitate pre-trial release approvingly notes that defendants let go after the relaxation were no more apt to reoffend (17 percent) than those released under the older guidelines. To be sure, more crimes did happen. (A news account estimated 200-300 more per year.) But as the authors emphasized, a six-month increase in releases from 8,700 under the old guidelines to 9,200 under the new (5.7 percent) didn’t significantly affect crime citywide. Given Chicagoland’s formidable crime problem, that’s hardly surprising. But set the whole aside. What about the poverty-stricken Chicago neighborhoods where most releasees inevitably wind up? Did their residents notice a change? Was it for the better or worse?

Yet no matter how well it’s done, policing is clearly not the ultimate solution. Preventing violence is a task for society. As we’ve repeatedly pitched, a concerted effort to provide poverty-stricken individuals and families with child care, tutoring, educational opportunities, language skills, job training, summer jobs, apprenticeships, health services and – yes – adequate housing could yield vast benefits.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

That notion, which the Urban Institute and others have long championed, is nothing new. And while there are some promising nonprofit initiatives – say, Habitat for Humanity’s neighborhood revitalization program – most efforts at urban renewal focus on rehabilitating physical space and helping industries and businesses grow. In today’s Washington Post, mayors representing cities in Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia and Kentucky peddled a “Marshall Plan” for Middle America that would create jobs through major investments in renewable power. While that could ostensibly yield great benefits, it hardly addresses the needs of the scores of unskilled, under-educated, poorly-served denizens of our inner cities. That, however, is the goal of Jobs-Plus, a long-standing HUD program that offers employment and educational services to the residents of public housing in designated areas. Its budget? A measly $15 million. Nationwide.

Meanwhile impoverished communities continue to reel from crime and disorder. So here’s a hint for Mr. Biden, who absent a coup, will assume the throne in January. Your predecessor talked up a good idea. Alas, it was just that: “talk.” America urgently needs to invest in its impoverished neighborhoods. A comprehensive “Marshall Plan” that would raise the educational and skill levels and improve the job prospects, lives and health of the inhabitants of these chronically distressed places seems the logical place to start.

UPDATES (scroll)

5/19/25 “[When] folks know that you're watching, they go somewhere else.” That, according to the leader of a Detroit citizen’s radio patrol program, is what accounts for his area’s steep reduction in burglaries. And for an observable drop in gang activity, prostitution and drug sales as well. Since the pandemic, though, the number of Detroit areas festooned with citizen patrollers is substantially down. But in the Greenacres-Woodward neighborhood, they remain a strong presence.

12/13/23 DOJ’s just-released “Violent Crime Reduction Roadmap” urges that cities adopt the Council on Criminal Justice’s “ten steps” for reducing violence. Step #5 urges “a combination of place-based policing and investment.” For the latter, it suggests “targeted investments and deployment of resources [to] improve education, employment, healthcare, housing, transportation, and other socioeconomic factors that can give rise to crime and violence in the first place”.

11/27/23 Chicago CRED provides youths who live in the city’s most highly violence-impacted neighborhoods “with a modest stipend, a life coach, trauma treatment, education and job training.” According to a recent study, young men who complete the two-year program are significantly less likely to be subsequently arrested for a violent crime. But their victimization rate is not yet provably affected. CRED website Study

11/14/23 “An Unlikely Partnership.” That’s how BJA describes its Community Based Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative. It has funded eighty-six programs in crime-beset inner-city neighborhoods that partner police, affected residents and gang members in collaborations that “prevent violence, strengthen community resilience, and build social capital”. As part of this approach, former inmates are provided job opportunities and involved in “intensive, long-term programs designed to change their behavior.”

12/15/22 In late 2015 Hesperia, Calif. adopted a “crime-free” program that directed property owners to clear prospective tenants of rental homes and apartments with the Sheriff’s Dept. and deny housing to those deemed unsuitable because of present or past misdeeds. In July the Dept. of Justice sued to halt this practice for illegally discriminating against Blacks and Hispanics. Hesperia recently settled the suit by discontinuing the program and paying damages to those who were unlawfully displaced.

12/9/22 A study reveals that Chicago’s needy neighborhoods receive only a small fraction of investments. During 2010-2020 those whose inhabitants were more than 80 percent White received $32,707 per household, 3 1/2 times the amount ($9,372) allocated to neighborhoods where fewer than twenty percent were White. Public funds and charities can’t make up the difference. While they “poured” $9 billion into neighborhoods, private investors spent “nearly $200 billion” elsewhere. Urban Institute

11/22/22 “Reducing Racial Inequality in Crime and Justice,” a massive new report by the National Academy of Sciences, proposes that reducing the number of police stops and searches, cutting back on “jail detention, prison admission, and long sentences,” and improving the socioeconomic conditions of neighborhoods can ease the pronounced racial and ethnic disparities produced by America’s criminal justice system.

11/16/22 Thirty-two members of the rival WOOO and CHOO street gangs, which beset housing developments in New York City’s embattled Brownsville neighborhood, have been indicted for crimes ranging from weapons possession and reckless endangerment to murder. According to the Brooklyn D.A., these charges reflect twenty-seven episodes of inter-gang warfare over a two and-one-year period. And as they exchanged gunfire, innocent citizens also got hurt. “There’s no thinking about the terrible consequences that this behavior is causing in their community,” said D.A. Eric Gonzalez.

10/11/22 NIJ’s brand-new release, “Criminal Victimization, 2021,” reports a profound decline in the rate of violent victimization since the early nineties. However, urban areas experienced a significant uptick during 2020-2021. Persons in lower-income brackets were by far the most affected. For example, in 2021 residents at the bottom of the earnings scale suffered violent crime victimization rates of 29.6 per 1,000, while the rates for the wealthiest was a far lower 9.7.

10/6/22 DOJ is distributing nearly $100 million in grants to State, local and tribal governments and non-profits who provide housing, educational, employment and other services to formerly incarcerated persons to facilitate re-entry and prevent recidivism. In a related effort, DOJ has partnered with the Dept. of Education to fund post-secondary education for imprisoned persons through the Pell program.

9/17/22 In two beset Tulsa neighborhoods, a public-private partnership that enhanced the police presence, “shifted high-risk individuals away” through eviction and provided enhanced security and surveillance significantly reduced total crime. But there was no significant reduction of disorderliness, and assaults only fell significantly in one location.

2/26/22 A city-funded “basic income plan” that provides 500 low-income Chicago households with $500 each month for one year kicks off in April. Households must have been financially impacted by the pandemic and their income must be less than 250% of the poverty level. For example, a three-member household’s present yearly income cannot exceed $57,575. Chicago also offers one-time awards of $500 to domestic workers and to persons, including illegal immigrants, who cannot obtain Federal payments.

12/21/21 DOJ is awarding $1.6 billion in grants to police, prosecutors and community organizations to support violence reduction programs, including evidence-based law enforcement strategies, crisis intervention for drug abusers and the mentally ill, and assistance for releasees transitioning to society.

12/14/21 A new academic study that analyzed the effects of “racial and economic segregation” in thirteen cities during the pandemic concluded that in 2020 gun violence, aggravated assault and homicide were at significantly higher levels in “marginalized” ZIP codes, and that the disparity between privileged and unprivileged areas had increased since 2018.

11/11/21 To help the “more than 8,500 people who leave its prisons every year...with only a bus pass and a small sack of belongings,” Colorado is spending nearly a million dollars to develop a list of employers who will hire newly-released inmates. Smaller amounts are going to private organizations that assist new releasees.

10/30/21 While the details are still to be worked out, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s proposal to grant $500 monthly payments for a year to 5,000 households comprised of “very low-income residents who have been economically hard-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic” is in her city’s newly-passed budget. Critics worry that these “handouts” will remove the incentive to work and be misused. But a former Stockton, Calif. mayor says that a similar program in his city worked well (see 7/9/21 update.)

10/25/21 With $10 million in state subsidies and millions more from private donors, a charitable organization is erecting two single-family residences in Chicago’s impoverished North Lawndale neighborhood. Fifty more are planned. It’s intended that the homes be purchased by low-income families, who will hopefully benefit from zero-interest and other financial incentives that are in the works.

10/11/21 In Philadelphia, up to 29-percent reductions in violence were experienced in the poverty-stricken blocks surrounding vacant parcels that got either a thorough cleanup or a major “clean and green” intervention. In a second study, a “full remediation” of abandoned homes led to “a clear reduction in weapons violations, gun assaults and shootings” in nearby areas. According to the authors, such findings suggest that high-need locations “may benefit the most from place-based investment.”

10/4/21 Five Chicago neighborhoods beset by gangs and gun violence will be getting special attention. It’s a carryover from a summer program that selects up to six neighborhoods for a mix of concentrated policing and social services. Officers will focus on problematic persons and locations, while residents will be helped to “find jobs, fight drug addiction and connect with assistance programs.”

9/22/21 Organized as the “Watch Guard,” adult male residents of Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood patrol their neighborhood in private vehicles each night, monitoring police radio traffic and using cell apps to communicate. “We watch anything that may be strange going on,” said its founder, a martial artist, “and do our best to de-escalate things, report and document. Their creed: “Black people are valuable and worthy of protection and compassion.” Their mission: “Rebuilding and reconnecting the village through service to our people.”

8/23/21 Police shot and killed Octavia Mitchell’s 18-year old son in 2010. Three years later, a street shooting took the life of Dedra Morris’s son. Both channeled their grief into “Warrior Moms,” a group that organizes events for children who live in Chicago’s most violent neighborhoods. On this occasion they were taking fifty youngsters by bus to Six Flags theme park. Mitchell is convinced that such experiences can make a difference. “To see their eyes light up and enjoy themselves in peace was priceless.”

8/20/21 Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood is getting the city’s first “Community Safety Coordination Center.” Mayor Lori Lightfoot said it would use a “whole-of-government approach” to combat violence by bringing residents and officials together to tackle “systemic inequities” including “quality housing, health care and social services.” Current initiatives that address “community safety, health and well-being, and violence interruption” will also be housed at the centers.

7/26/21 According to Washington D.C, police, over forty percent of gunfire occurs in a beset region that comprises only two percent of the District. Crime scene technicians found nearly 2,800 bullet casings within a square-mile stretch of that area in three years. Killings are so commonplace that a local mentor stopped going to funerals and now works with young people in Virginia: “I’m tired of praying over a person in a casket that I played pee-wee football with.” In 2020 murders in D.C. “reached a 16-year high,” leading its Democratic mayor, Muriel E. Bowser, to declare “a public health crisis.”

7/18/21 With 102 murders in Washington D.C. so far this year, same as in 2020 and a sixteen-year high, the Nation’s capital reels from the death of its latest victim, a six-year old girl who was gunned down in a drive-by that wounded five others, including her mother. Meanwhile the city announced a new program, Building Blocks DC, “that concentrates police and health programs on the 151 blocks where gun violence is most common.”

7/13/21 At a White House meeting with political leaders and police chiefs, President Biden urged a multi-pronged approach against crime. It would include a crackdown on rogue gun dealers, hiring more cops, and funding community policing, housing, mental health and job training programs. “Support young people to pick up a paycheck instead of a pistol,” he implored. Memphis police chief C.J. Davis agrees. Noting that “Black and Brown communities are being terrorized from gun violence,” he’s convinced that more than policing is needed. “We have to find balance. We can’t continue to arrest crime away.”

Similar sentiments were voiced in a major Chicago Tribune editorial about the violence-beset city. Community members emphasized addressing “root causes” including “poverty and inequity, low employment opportunities in under-resourced neighborhoods, high dropout rates in education, and the long-standing tension between law enforcement and the community.” One, who warned that defunding police is “stupid,” urged that cops could best be helped by paying everyone who works “a living wage.”

7/9/21 Long Beach is planning to supplement the income of 500 of its poorest families with a monthly stipend of $500 for a year. Childcare, work training and transportation will also be furnished. Its effort follows on “universal basic income” successes elsewhere. For example, Stockton, whose program began in 2019, reports that recipients are “healthier, showing less depression and anxiety and enhanced well-being” and more likely to find a good job.

7/8/21 President Biden’s “American Families Plan” would offer a variety of benefits, and particularly to lower-income families. These would include universal pre-school, free childcare, paid family and medical leave, “healthy” home and school meals, special tax credits, and mentoring, free college education and direct monetary assistance to financially struggling students.

6/29/21 An outreach initiative aimed at “men most likely to experience gun violence,” READI Chicago offers intensive individualized services including cognitive therapy, job training and placement, education and health care. Proponents argue that its cost, $20,000 per year, is a lot cheaper than prison, and its results have impressed President Biden, who referred to the program in a recent speech.

6/23/21 California legislators have tentatively agreed to use Federal COVID funds to cover the full amount of unpaid rent accumulated by low-income persons during the pandemic. Assistance with utility bills would also be provided. Another program would be available to families with earnings less than eighty percent of the local median.

5/13/21 California Governor Gavin Newsom’s plate of education initiatives includes an initial $1 billion outlay, which would eventually increase five-fold, to fund after-school and summer enrichment and tutoring programs in “low-income communities.”

12/26/20 Court injunctions that forbid persons identified by police as gang members from congregating have been issued throughout California since the violence-wracked 1980s. About 8,600 residents of Los Angeles are included. But litigation by the ACLU has led to a settlement which forbids LAPD from arresting alleged violators of gang injunctions unless their membership has been proven in court.

12/23/20 L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti rejected the City Council’s proposal to use reallocated police funds for “park improvements, street and alley resurfacing, tree trimming” and other physical repairs. Instead, he wants to direct the funds for social purposes, including avoiding the layoff of city workers, “antiviolence initiatives,” and a program that has mental health specialists respond to nonviolent calls.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Special topic: Neighborhoods

More Poverty, Less Trust Is Crime Really Down? It Depends... Shutting the Barn Door

America’s Violence-Beset Capital City See No Evil - Hear No Evil Watching the Watchers

Good News/Bad News Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job (I) (II) Does Race Drive Policing?

Race and Ethnicity Aren’t Pass/Fail Hard Times in “The Big Easy” Massacres, in Slow-Mo

What’s Up? Violence “Woke” up, America! Let’s Stop Pretending Four Weeks, Six Massacres

Cop? Terrorist? Both? Don’t “Divest” - Invest! Place Matters Repeat After Us Human Renewal

Mission Impossible? Scapegoat (I) (II) Location, Location, Location Is Trump Right?

RELATED ARTICLES AND REPORTS

Sources of Crime Guns in Los Angeles, California

Urban Institute: Exploring Capital Flows in Chicago (2022)

Tackling Persistent Poverty in Distressed Urban Neighborhoods (2014)

John Jay: Memo to Joe Biden: Focus on Neighborhood Safety (The Crime Report, Dec. 7, 2020)

Mayor’s Plan for Neighborhood Safety (2019) Reducing Violence Without Police (2020)

HUD: Jobs-Plus Neighborhoods and Violent Crime (2016)

Posted 11/11/20, edited 11/21/21

WHEN MUST COPS SHOOT? (PART II)

“An ounce of prevention…” (Ben Franklin, 1736)

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Part I described four problematic encounters that officers ultimately resolved by gunning someone down. Each citizen had presented a substantial threat: two flaunted knives, one went for a gun, and another reportedly used a vehicle as a weapon. Yet no one had been hurt before authorities stepped in. Might better police work – or perhaps, none at all – have led to better outcomes?

Let’s start with a brief recap:

- Los Angeles: A 9-1-1 call led four officers to confront a “highly agitated” 34-year old man running around with a knife. A Taser shot apparently had no effect, and when he advanced on a cop the officer shot him dead.

- Philadelphia: A knife-wielding “screaming man” whose outbursts led to repeated police visits to his mother’s residence chased two officers into the street. As in L.A., he refused to drop the weapon, and when he moved on a cop the officer fired.

- San Bernardino, California: A lone officer confronted a large man who was reportedly waving a gun and jumping on parked cars. He refused to cooperate and a violent struggle ensued. During the fight the man reached for a gun. So the cop shot him dead.

- Waukegan, Illinois: A woman suddenly drove off when a cop tried to arrest her passenger/boyfriend on a warrant. (See 10/14/24 update) Another cop chased the car, and when it ran off the road the officer approached on foot. He quickly opened fire, supposedly because the car backed up at him. Its driver was wounded and her passenger was killed.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

Consider the first two instances. Agitated, mentally disturbed men went at cops with knives. Might a Taser strike have stopped them in their tracks? A decade ago, when Tasers were an up-and-coming tool, their prospects seemed limitless. Don’t physically tangle with an evil-doer. Don’t beat them with a club. Zap them instead! But as we discussed in a two-parter (“Policing is a Contact Sport,” I and II) that enthusiasm was soon tempered. Some citizens proved highly vulnerable to being zapped, and a substantial number died.

Other issues surfaced. A 2019 in-depth report, “When Tasers Fail,” paints a decidedly gloomy picture. Recounting a series of episodes in which Tasers failed to stop assailants, including some armed with knives, it concluded that Tasers – and particularly its newest versions – was far less reliable than what its manufacturer claimed. For the relatively clumsy and uncertain tool to be effective its pair of darts must pierce the skin (or come exceedingly close) and be separated by at least one foot. That requires an accurate shot from a moderate distance. Even then, darts can be pulled out, and officers usually get only two shots before having to replace the cartridges. Even when darts are accurately placed, some persons are unfazed when struck while others become even more violent. A use-of-force expert adept with Tasers conveyed his colleagues’ change of heart:

When electronic defense weapons first came on the market, the idea was that they would be used to replace lethal force. I think that was sort of a misnomer.

Tasers were never meant to keep cops from being killed. That’s always been a job for firearms. Even then, nothing’s guaranteed. When an angry someone armed with a knife is only a few feet away (supposedly, less than 21 feet) a cop may have insufficient time to unholster his weapon and shoot. Even with a gun in hand, firing under pressure often proves inaccurate. Bottom line: when facing a deadly threat, drawing one’s pistol well in advance, per the officers in Los Angeles and Philadelphia, is essential.

Yet Los Angeles, which deploys two-officer units, had four cops on hand. Couldn’t they have effectively deployed a Taser before the suspect closed in? Actually, during the chase one cop apparently tried, but the suspect was running, and there was no apparent effect. LAPD’s overseers at the Police Commission ultimately ruled that the shooting was appropriate. But they nonetheless criticized the officers for improperly staging the encounter. Police Chief Michel Moore agreed. In his view, the sergeant should have organized the response so that one officer was the “point,” another the “cover,” and another in charge of less-than-lethal weapons. Chief Moore was referring to a well-known strategy, “slowing down.” Instead of quickly intervening, cops are encouraged to take the time to organize their response and allow backup officers, supervisors and crisis intervention teams to arrive.

Might “slowing down” have helped to defuse what happened in San Bernardino or Waukegan?

- As San Bernardino’s 9-1-1 caller reported, the bad guy was indeed armed with a gun. He also vastly outsized the officer and the struggle could have easily gone the other way (click here for the bystander video.)

That the cop didn’t “slow down” probably reflected his worry about the persons in the liquor store where the suspect was headed. Waiting for backup would have risked their safety. So for that we commend him. Still, it’s concerning that he was left to fend for himself. Cities that deploy single-officer cars – and these are in the clear majority – normally dispatch multiple units on risky calls. Lacking San Bernardino’s log we assume that other officers were tied up. There’s no indication that the actual struggle was called in, so dispatch might have “assumed” that all was O.K. Really, for such circumstances there’s no ready tactical or management fix. Assuring officer and citizen safety may require more cops. And at times like the present, when taking money from the cops is all the rage, good luck with that.

- Waukegan was different. Neither of the vehicle’s occupants posed a risk to innocent citizens. But the officer who originally encountered the couple tried to do everything, including arresting the passenger, on his own. That complete self-reliance was duplicated by the cop who chased down the car. His lone, foot approach was unfathomably risky. Additional units could have provided cover, a visible deterrent and a means of physical containment. After all, the first officer was apparently still available. But the second cop didn’t wait, and the consequences of that decision have resonated throughout the land. No doubt, “slowing down” would have been a good idea. (See 9/28/22 and 10/14/24 updates)

Could the L.A. and Philadelphia cops have waited things out? Watch the videos (click here for L.A. and here for Philly.) Both situations posed a clear, immediate risk to innocent persons. Agitated suspects who move quickly and impulsively can defeat even the best laid plans and create a situation where it’s indeed “every officer for themselves.” Worse yet, should a bad guy or girl advance on a cop before they can be “zapped,” other officers may have to hold their fire, as discharging guns or Tasers in close quarters can easily injure or kill a colleague. And such things do happen.

So what about doing…nothing? In Waukegan there was really no rush. Waiting for another day might have easily prevented a lethal outcome and the rioting that followed. That, in effect, is the “solution” we peddled long ago in “First, Do no Harm.” Here’s how that post began:

It’s noon on Martin Luther King day, January 17, 2011. While on routine patrol you observe a man sleeping on the sidewalk of a commercial park…in front of offices that are closed for the holiday. A Papa John’s pizza box is next to him. Do you: (a) wake him up, (b) call for backup, then wake him, (c) quietly check if there’s a slice left, or (d) take no action.

To be sure, that gentleman was threatening no one and seemed unarmed. So the medical tenet primum non nocere – first, do no harm – is the obvious approach. But police in Aurora, Colorado have substantially extended its application. Here’s how CBS News described what happened in the Denver suburb on two consecutive days in early September:

…Aurora police officers twice walked away from arresting a 47-year-old man who was terrorizing residents of an apartment complex, even after the man allegedly exposed himself to kids, threw a rock through one resident’s sliding glass door, was delusional, was tasered by police and forced the rescue of two other residents from a second floor room in an apartment he had ransacked.

According to a deputy chief, backing off was appropriate and prevented injuring the suspect or the cops. After all, officers ultimately went back and took the man into custody without incident. Yet as a Denver PD lieutenant/CJ professor pointed out, innocent citizens were twice abandoned and left at risk. “It was a serious call to begin with since it involved a child...I would not have left the guy two successive days, probably not even after the first call.”

Aurora’s laid-back approach remained in effect. On September 24 a team of officers staked out the residence of a suspected child abuser who had a no-bail domestic violence warrant from Denver. He refused to come out and was thought to be well armed. So the cops eventually left. They later discovered that the man had an outstanding kidnapping warrant. But when they returned he was gone. And at last report he’s still on the lam.

Check out the that post’s reader comments. Not all were complementary. Police undoubtedly feel torn. But the killing of George Floyd struck a chord and led to rioting in the city. You see, one year earlier, on August 24, 2019, while Aurora’s cops were still operating under the old, more aggressive approach, they forcefully detained Elijah McClain, a 21-year old Black pedestrian whom a 9-1-1 caller reported was behaving oddly. McClain forcefully resisted, and during the struggle officers applied a carotid hold. On arrival paramedics diagnosed excited delirium syndrome (exDS) and injected a sedative (ketamine). McClain soon went into cardiac arrest and died days later at a hospital. On February 22, 2021 an official city report concluded that police did not have adequate cause to forcefully detain or restrain Mr. McClain and that officers and paramedics badly mishandled the situation. A wrongful death lawsuit was subsequently settled for $15 million (see 11/22/21, 1/21/23, 10/16/23, 11/6/23, 12/26/23 and 1/8/24 updates).

Yet we’re reluctant to suggest doing nothing as a remedy. Imagine the reaction should an innocent person be injured or killed after cops back off. And while we’re fond of “de-escalation,” the circumstances in our four examples seem irreparably conflicted. Consider the suspects in San Bernardino and Waukegan. Both had substantial criminal records and faced certain arrest: one for carrying a gun and the other for a warrant. Yet officers nonetheless tried to be amiable. (Click here for the San Bernardino video and here for Waukegan.) In fact, being too casual may have been part of the problem. Our personal experience suggests that gaining voluntary compliance from persons who know they’re going to jail calls for a more forceful, commanding presence.

Great. So is there any approach that might have averted a lethal ending? “A Stitch in Time” suggests acting preventively, preferably before someone runs around with a gun or brandishes a knife. Police departments around the country have been fielding crisis-intervention teams with some success (see, for example, our recent discussion of the “Cahoots” model.) New York City is presently implementing a mental health response that totally cuts out police; that is, unless “there is a weapon involved or ‘imminent risk of harm.’” As even Cahoot’s advocates concede, once behavior breaches a certain threshold even the most sophisticated talk-oriented approach may not suffice.

And there’s another problem. While we’re fans of intervening before situations explode, in the real world of budgets and such there’s usually little substantial follow-through. We’re talking quality, post-incident treatment, monitoring and, when necessary, institutionalization. Such measures are intrusive and expensive, and that’s where things break down. That means many problematic citizens (e.g., L.A., Philly, San Berdoo, Waukegan) will keep misbehaving until that day when…

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Full stop. Officers resolve highly conflicted situations every day as a matter of course. But unlike goofs, which get big press, favorable outcomes draw precious little attention and no respect. Yet knowing how these successes came to be could be very useful. (Check out the author’s recent article about that in Police Chief.)

We’re not holding our breath. During this ideologically fraught era only one-hundred percent success will do. Consider this outtake from a newspaper account about the incident in San Bernardino:

During a news conference Friday morning, the police sought to portray [the suspect] as physically intimidating, listing his height and weight — 6 feet 3 and 300 pounds — and cataloging what they called his “lengthy criminal past,” prompting one bystander to remark, “What does that have to do with him being murdered?

Alas, that attitude pervades the criminal justice educational community. Many well-meaning academics have been rolling their eyes for years at our admittedly feeble attempts to reach for explanations in the messy environment of policing. Their predominant P.O.V. – that poor outcomes must be attributed to purposeful wrongdoing – has apparently infected L.A. City Hall as well. At a time when “homicides and shootings soar to levels not seen in the city in a decade,” the City Council just decided to lop $150 million off LAPD’s budget and shrink its force by 350 sworn officers.

Was that move well informed? Did it fully consider the imperatives and constraints of policing? And just what are those? If you’re willing to think, um, expansively, print out our collected essays in compliance and force and strategy and tactics. As long as you promise to give them away, they’re free!

UPDATES (PARTS I & II) (scroll)

6/4/25 Last year a 9th. Circuit panel ruled 2-1 that the “qualified immunity” doctrine protected LAPD officer Toni McBride from being sued for continuing to fire at an assaultive man after he was wounded and laying on the ground. But an en banc panel of the Court just cited an earlier case in which it held that “continuing to shoot a suspect who appears to be incapacitated and no longer poses an immediate threat violates the Fourth Amendment.” And whether it was violated in this matter is for a fact-finder to decide. So the case is back with the District court; and presumably, for a trial by jury. 9th. Circuit decision (See 1/13/23, 3/25/24 and 10/7/24 updates)

4/15/25 Former Colorado deputy sheriff Andrew Buen was sentenced to three years imprisonment for the 2022 shooting death of a deeply disturbed motorist who had called police. Christian Glass flashed a knife when officers approached, and Buen promptly fired. In 2024 a jury convicted him of misdemeanor recklessness, but jurors hung up on murder. When retried, Buen was convicted on the lesser offense of criminally negligent homicide. At sentencing Buen, who has been in jail, apologized to the victim’s family and agreed that he was fully to blame. (See 4/29/24 update)

3/4/25 Calling it “unjust” and disproportionate, Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin commuted the three-year prison term just handed down to former Fairfax County (Va.) police sergeant Wesley Shifflett for shooting and killing Timothy McCree Johnson in 2023. Shifflet will, however, remain convicted of felony reckless handling of a firearm. Johnson’s mother disparaged the commutation as “validating” the killing. (See below update)

3/3/25 Two years ago former Fairfax County (Va.) police sergeant Wesley Shifflett shot and killed a shoplifter who “reached for his waist” during a foot chase. Timothy McCree Johnson, 37, turned out to be unarmed. At trial, then-Sgt. Shifflett was acquitted of manslaughter but convicted of felony reckless handling of a firearm. He was just sentenced to three years imprisonment. Bodycam video (See 10/7/24 and above updates)

1/24/25 Sixteen years. That’s the prison sentence handed down to former Auburn, WA police officer Jeffrey Nelson, whom a state court jury convicted of murder and assault. In 2019 then-officer Nelson tangled with an unarmed homeless man, and shot him dead when he allegedly reached for his gun. As of 2018 state law no longer requires evidence that an officer acted with malice, but proof is still needed that the force used was unreasonable or unnecessary. Nelson, who had a reputation for using force, had previously killed two other persons while on duty, one in 2011 and another in 2017.

11/26/24 Twenty-million dollars. That’s what the city of Las Cruces, NM has agreed to pay the estate of Teresa Gomez, who was shot and killed by ex-cop Felipe Hernandez during an October 2023 nighttime encounter outside a housing complex. As the cop berated her and her passenger, who was supposedly barred from the premises, Ms. Gomez suddenly drove off with her car door still open. Hernandez instantly opened fire. He awaits trial for second-degree murder. Press briefing, with bodycam

11/25/24 On November 12 Las Vegas resident Brandon Durham called 911 to report that he and his daughter were hiding from a person who just broke into their home. And as he and the intruder struggled over a knife, Officer Alexander Bookman burst in. He soon opened fire, and Mr. Durham was shot dead. The intruder, Alejandra Boudreaux, was arrested, and the officer was placed on leave. Boudreaux – reportedly Mr. Durham’s one-time paramour – has a lengthy criminal history

11/21/24 In March 2021 then-L.A. County deputy sheriff Remin Pineda kept shooting at David Ordaz Jr. even though the man, who had threatened family members with a knife, was struck by bullets fired by other officers and had fallen to the ground. Mr. Ordaz died. A plea bargain to let Pineda plead guilty to felony assault under color of authority had been rejected by a judge. But although Ordaz’s survivors bitterly objected, another judge just approved the deal. Pineda will not have to serve any prison time. (See 8/1/21 and 11/2/22 updates)

11/14/24 In November 2017 U.S. Park Police officers Lucas Vinyard and Alejandro Amaya shot and killed Bijan Ghaisar when he nearly struck one of them with his car while trying to flee from a car stop. They were charged with manslaughter, but a Federal judge dismissed the case. And an attempt to fire them was just turned away by the Interior Dept.’s Inspector General, who ruled the shooting justified. Last year the Government settled the family’s suit for $5 million; both officers remain on paid leave. (See 6/25/22 and 4/24/23 updates)

10/14/24 In a message to PoliceIssues, the mother of Marcellis Stinnette, who was shot and killed by a then-Waukegan, Ill. police officer four years ago, states that “after investigations , it was founded that there was no active warrant for my son. My family had been harassed by the same officer for years prior to him murdering my son.” (See 9/28/22 update)

10/7/24 One year ago Fairfax County (Va.) police sergeant Wesley Shifflett and another officer chased Timothy

McCree Johnson, 37 after he shoplifted a pair of sunglasses. As they entered a dark wooded area Sgt. Shifflett said Mr. Johnson reached for his waist. Both officers fired their guns. Sgt. Shifflett’s rounds killed Mr. Johnson, who was unarmed. Mr. Johnson was Black; both officers are White. Sgt. Shifflett was fired. At his recentl trial jurors acquitted him of manslaughter but convicted him of felony reckless handling of a firearm. According to the original story, Sgt. Shifflett had pointed his gun at other shoplifters in the past. (See 3/3/25 update)

LAPD officer Toni McBride remained on the job after Chief Bernard Parks held that her April 2020 shooting of Daniel Hernandez, who aggressively flaunted a box cutter, was “in policy”. But the Police Commission disagreed because her last two rounds were fired while Hernandez was on the ground. McBride appealed, and a hearing examiner just reversed the Commission. McBride is now fully cleared. (See 1/13/23, 3/25/24 and 6/4/25 updates)

9/17/24 In March former Colorado paramedic Peter Cichuniec drew a five-year prison term for injecting Elijah McClain with ketamine during his forceful restraint by police. McClain didn’t survive. Cichuniec’s paramedic partner was also convicted but drew probation. Taking pity on Cichuniec, the sentencing judge just released him on probation as well. Cichuniec had been a firefighter/paramedic for eighteen years. According to the judge, the “deterrence” effect was served. (See 3/4/24 update)

8/26/24 Manslaughter charges were filed against former Okaloosa Co., Fla. deputy sheriff Eddie Lee Duran Jr. for the shooting death of a man who answered his door while armed. Roger Fortson’s pistol was pointing down when the deputy arrived in response to a domestic disturbance call. But the deputy instantly fired. As it turns out, he might have been directed to the wrong apartment. (See 6/3/24 update)

8/16/24 During the evening hours of July 13 a plainclothes LAPD officer followed a car occupied by four ski-masked men who had just been involved in a confrontation with another vehicle at a South Los Angeles intersection. Suddenly the car being followed stopped and one of its occupants ran up to the driver-side door of the officer’s car. Sgt. Michael Pounds instantly opened fire through his window, fatally wounding Ricardo “Ricky” Ramirez Jr., 18. He turned out to be unarmed. His family’s lawyer is urging the officer’s prosecution. He called it a “case of shoot and ask questions later.” LAPD videos

8/14/24 In violence-beset Baltimore, the police killing of an admittedly armed teen was bitterly criticized by residents who felt that his having a gun was insufficient reason to open fire. But police insist that 17-year old William Gardner pointed the gun at officers during a foot pursuit. Whether that’s true isn’t clear from officer bodycams. Police Commissioner Richard Worley, who called the incident “tragic”, said that officers had repeatedly told the youth to drop his pistol during the chase. But he didn’t.

7/17/24 Fullerton, Calif. 9-1-1 dispatchers were alerted by a male caller that he and others were being threatened by a man armed with knives. A two-officer patrol car quickly spotted the man and stopped some distance away. One officer pointed his pistol; the other pointed a rifle. They asked the man to put the knives down, but after a brief delay he charged at the patrol car with knives raised as if to strike. Officers promptly shot him dead. It turned out that the man had called 9-1-1 on himself. News release Video

7/9/24 An inquiry by the Los Angeles Times reveals that so far this year LAPD officers have shot six mentally-afflicted persons who were flaunting “a sharp object”, killing four. There were a total of 11 such shootings last year. This year’s outcomes were recently addressed by the Police Commission’s vice president, who said “I want to make sure that all other efforts are exhausted before lethal force is used.” But while the article’s tone implicitly criticizes the police, it also conveys concerns about the effectiveness of less-lethal weapons such as projectile launchers.

6/3/24 Okaloosa County, Fla. deputy Eddie Duran, who shot and killed airman Roger Fortson during a disturbance call on May 3, has been fired. Sheriff Eric Arden determined that although airman Fortson was holding a pistol when he answered his apartment door, the gun was pointed at the ground and he “did not make any hostile, attacking movements.” Duran’s use of deadly force was therefore “not objectively reasonable.” But the former deputy states that the airman seemed aggressive. “I’m standing there thinking I’m about to get shot, I’m about to die.” Whether another resident of the complex directed the deputy to the wrong apartment is also in dispute. Bodycam video (See 8/26/24 update)

4/29/24 Eight rural Colorado law enforcement officers were criminally charged over the June, 2022 shooting death of Christian Glass, a drug-impaired driver who called for assistance after getting stuck but flashed a knife when approached. Andrew Buen, the former deputy who fired the lethal rounds, was just convicted of reckless endangerment, but jurors hung up on second-degree murder and official misconduct. Seven other officers were charged with misdemeanor failure to intervene; a supervisor pled guilty and got two years probation; the other officers are yet to be tried. (See 11/25/22 and 4/15/25 updates)

4/17/24 After the foreperson announced the panel was deadlocked 7-5, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge declared a mistrial in the case against ex-schools cop Eddie Gonzalez. Charged with 2nd. degree murder for shooting and killing a passenger in a car that he approached after an altercation on a nearby campus, Gonzalez insisted that he fired because the car’s sudden movement placed him in danger. But that’s been strongly disputed. According to the foreman, the holdouts favored a manslaughter conviction. A lawsuit against the school district was settled for $13 million last year. A retrial is pending. (See 10/28/21 update)

4/11/24 Twenty-five million. That’s what L.A. County has agreed to pay Isaias Cervantes, a seriously mentally-ill man who was shot and paralyzed during a 9-1-1 response. Family members called because Cervantes had become combative during a “mental health crisis”, and he tried to fight off deputies when they tried to handcuff him. One deputy repeatedly exclaimed “he's going for my gun,” and another opened fire. LASD declared the shooting “in policy,” and the D.A. declined to prosecute. Video (See 1/10/22 update)

3/25/24 Qualified immunity forbids civil rights lawsuits against individual police officers unless they “clearly violated” a law. That, according to a recent Ninth Circuit ruling, shields LAPD officer Toni McBride from a lawsuit filed by the family of Daniel Hernandez, whom she shot dead in 2020. That’s so even though the LAPD Commission had ruled that her final two shots, once Hernandez was on the ground, were out of policy. But Chief Michel Moore disagreed, and officer McBride went unpunished. (See 1/13/23, 10/7/24 and 6/4/25 updates)

3/18/24 A Connecticut jury acquitted ex-State trooper Brian North of manslaughter and negligent homicide for shooting and killing a mentally-troubled youth who flaunted a knife. In the 2020 incident, Mubarak Soulemane, 19 resisted arrest at the end of a pursuit and crash, and then-trooper North fired seven rounds because he thought, mistakenly as it turns out, that a fellow officer might be stabbed. A $10-million dollar wrongful death lawsuit remains in progress.

3/12/24 In Apple Valley, Calif., Sheriff’s deputies responded to a 9-1-1 call from a home where a teen was reportedly assaulting family members and causing damage. Seconds after the first deputy on scene approached the home’s open front door, 15-year old Ryan Gainer emerged from its interior aggressively wielding “an approximate five-foot-long garden tool, with a sharp bladed end.” Gainer ignored commands to “get back,” and the deputy, who had already drawn his pistol, shot him dead. Video

3/4/24 Five years in prison. That’s the sentence handed down to Colorado paramedic Peter Cichuniec for causing the death of Elijah McClain by forcefully, and needlessly, injecting ketamine on the struggling man. A jury convicted Cichuniec of assault, and this was the minimum term he could have received. Paramedic Jeremy Cooper is yet to be sentenced. Their convictions have been sharply criticized by the paramedic’s union, which says that their “scapegoating” is discouraging candidates from applying. (See 1/8/24, 2/6/24 and 9/17/24 updates)

2/6/24 In 2020, one year after their epic encounter with Elijah McClain, Aurora (CO) police stopped a car they (mistakenly) thought was stolen. Guns pointed, officers initially placed its upset driver, a Black woman, and her children, on the ground, face-down. A D.A.’s investigation did not lead to any charges against officers, and those involved remained on the force. But their conduct was deemed “unacceptable.” And the city has now settled the family’s lawsuit for $1.9 million. Video (See 3/4/24 update)

1/8/24 Former Aurora (CO) officer Randy Roedema was convicted last year of felony negligent homicide and misdemeanor assault in the 2019 death of Elijah McClain, a pedestrian whom a 9-1-1 caller reported had been acting oddly. Roedema was just sentenced to 14 months in jail. His two companion officers were also tried, but both were found not guilty. However, two paramedics were convicted for negligently injecting McClain with an excessive dose of ketamine. They will soon be sentenced (see below update).

Keep going...

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Acting? Or Re-acting? San Antonio Blues What Were They Thinking? A Partner in Every Sense

When Must Cops Shoot? (I) L.A. Wants “Cahoots” Fair but Firm Violent and Vulnerable

No Such Thing as Friendly Fire Speed Kills A Reason? There’s No “Pretending” a Gun

De-Escalation A Stitch in Time First, Do no Harm Making Time Every Cop Needs a Taser

RELATED ARTICLES

Why do Officers Succeed?

Posted 10/31/20

WHEN MUST COPS SHOOT? (PART I)

Four notorious incidents; four dead citizens. What did officers face?

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Many of our readers teach in college and university criminology and criminal justice departments. (That, indeed, was your blogger’s last gig.) So for an instant, forget policing. Think about your last evaluation. Was the outcome fair and accurate? Did it fairly reflect – or even consider – the key issues you faced in the classroom and elsewhere?

If your answers were emphatically “yes” consider yourself blessed. The academic workplace is a demanding beast, with a “clientele” whose abilities, attention span and willingness to comply vary widely. And we’re not even getting into administrative issues, say, pressures to graduate as many students as possible as quickly and cheaply as possible. Or the personalities, inclinations and career ambitions of department chairs. (If you’re one, no offense!) Bottom line: academia is a unique environment. Only practitioners who face it each day can truly understand the forces that affect what gets accomplished and how well things get done. Actually, that’s true for most any complex craft. Say, policing.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

So what is it that cops face? Let’s dissect four recent, notorious examples. Two involved mentally troubled men with knives, one a rowdy ex-con packing a gun, and one a young, non-compliant couple whose male half had amassed a substantial criminal record and was apparently wanted by police.

Los Angeles, November 19, 2019

Last November a citizen alerted an LAPD patrol sergeant that a man was running around with a knife (photos above.) Officers soon encountered a highly-agitated 34-year old male flaunting a “seven-inch kitchen knife.” Officers took off after him on foot (click here for the officer bodycam video).

During the chase one cop reportedly fired a Taser but without apparent effect. Soon the man paused. As his pursuers tried to keep their distance, Alex Flores swiftly advanced on one. His knife was in his right hand, with the blade pointed in and tucked under his forearm. After Mr. Flores ignored repeated commands to stop the officer shot him dead.

At a police commission hearing Mr. Flores’ grieving mother and sister argued that he wasn’t a criminal but a mentally ill man struggling with paranoia. “What type of system do you all serve?” his sister demanded to know. “Clearly this was a racist murder.”

Philadelphia, October 26, 2020

During the early morning hours of October 26 two Philadelphia police officers responded to a call about a “screaming man” with a knife.

Walter Wallace, Jr., 27, was flaunting his weapon on a second-floor porch, and when he spotted the officers he promptly came down the steps. Pursued by his mother, he briskly chased the cops into the street (left and center photos). Ignoring commands to drop the weapon, he kept on coming. So the officers shot him dead (right photo. For a bystander video click here.)

Mr. Wallace’s parents said that their mentally-disturbed son had been acting up despite being on medication. Indeed, police had already been at their home three times that very day. Their final call, they insisted, was for an ambulance, not the police. “His mother was trying to defuse the situation. Why didn’t they use a Taser?” asked the father. “Why you have to gun him down?” According to the police commissioner neither officer had a Taser, but the agency has been trying to get funds so that they could be issued to everyone.

San Bernardino, California, October 22, 2020

During the late evening hours of October 22 San Bernardino (CA) police were called about a large, heavyset man who was “waving around a gun” and “jumping on vehicles” in a liquor store parking lot.

A lone cop arrived. Spotting the suspect, he drew his pistol and yelled “hey man, come here” (left photo). But the six-foot-three, three-hundred pound man would have none of it. Disparaging the cop for drawing the gun, Mark Bender, 35, announced “I’m going to the store” and kept walking (right photo). Although the officer was vastly outsized he tried to physically restrain Mr. Bender, and the fight was on (click here for the officer bodycam video and here for a bystander video.) A lone cop arrived. Spotting the suspect, he drew his pistol and yelled “hey man, come here” (left photo). But the six-foot-three, three-hundred pound man would have none of it. Disparaging the cop for drawing the gun, Mark Bender, 35, announced “I’m going to the store” and kept walking (right photo). Although the officer was vastly outsized he tried to physically restrain Mr. Bender, and the fight was on (click here for the officer bodycam video and here for a bystander video.)

As the pair struggled on the ground, Mr. Bender pulled a 9mm. pistol from his pockets with his right hand (left and center photos). The cop instantly jumped away (right photo) and opened fire. Mr. Bender died at the hospital. His gun was recovered.

Police reported that Mr. Bender was a convicted felon with a lengthy criminal record. According to the Superior Court portal he was pending trial on a variety of charges including burglary, resisting police and felony domestic violence.

Waukegan, Illinois, October 20, 2020

About midnight, October 20th, a Waukegan (IL) officer interacted with the occupants of a parked car. According to the city’s initial version, an unidentified officer responded to a report of a suspicious car, but as he arrived the vehicle suddenly left. Another officer found it parked nearby. When he approached on foot the car went into reverse. Fearing he would be run over, the officer opened fire, badly wounding the driver, Tafara Williams, 20, and killing her passenger, Marcellis Stinnette, 19.

Given from the hospital where she is recovering, Ms. Williams’ account was starkly different. She and Mr. Stinnette were sitting in her vehicle, in front of their residence, when a cop drove up. He knew her boyfriend’s name and said he recognized him “from jail.” She asked if they could leave, then slowly drove off when the officer stepped back. But when she turned into another street her car was met by gunfire. Bullets struck her and Mr. Stinnette and caused the vehicle to crash. An officer kept firing even though she yelled they had no gun. "My blood was gushing out of my body. The officer started yelling. They wouldn’t give us an ambulance till we got out the car.”

Ms. Williams denied any wrongdoing. She doesn’t know what prompted the attack. “Why did you just flame up my car like that? Why did you shoot?” Once videos were released, however, what actually happened clearly varied from both accounts, and most dramatically from Ms. Williams’. Bodycam video from the officer who first encountered the couple reveals that he recognized Mr. Stinnette and announced that he was wanted on a warrant. But when the cop walked around to the passenger side (left photo shows his hand on the car) and told Mr. Stinnette that he was under arrest the vehicle abruptly sped away (right photo.) Ms. Williams denied any wrongdoing. She doesn’t know what prompted the attack. “Why did you just flame up my car like that? Why did you shoot?” Once videos were released, however, what actually happened clearly varied from both accounts, and most dramatically from Ms. Williams’. Bodycam video from the officer who first encountered the couple reveals that he recognized Mr. Stinnette and announced that he was wanted on a warrant. But when the cop walked around to the passenger side (left photo shows his hand on the car) and told Mr. Stinnette that he was under arrest the vehicle abruptly sped away (right photo.)

We now turn to dashcam video from the second police car (click here.) That officer took over the pursuit as the fleeing vehicle evaded the original responder. After running through a stop sign the vehicle turned right and ran off the road to the left (left photo). The officer abruptly stopped at the left curb alongside the vehicle (right photo) and exited his car. Gunfire soon erupted. His bodycam wasn’t on, so the officer’s claim that Ms. Williams backed up at him can’t be visually confirmed. But he accused her of that moments later once he had turned on his bodycam (click here for the clip.) This officer was promptly fired for not having the bodycam on and for other unspecified policy and procedural violations. We now turn to dashcam video from the second police car (click here.) That officer took over the pursuit as the fleeing vehicle evaded the original responder. After running through a stop sign the vehicle turned right and ran off the road to the left (left photo). The officer abruptly stopped at the left curb alongside the vehicle (right photo) and exited his car. Gunfire soon erupted. His bodycam wasn’t on, so the officer’s claim that Ms. Williams backed up at him can’t be visually confirmed. But he accused her of that moments later once he had turned on his bodycam (click here for the clip.) This officer was promptly fired for not having the bodycam on and for other unspecified policy and procedural violations.

Was Mr. Stinnette in fact a wanted person? We lack access to warrant information, but it seems likely (but see 10/14/24 update). He had accumulated a substantial felony record in Waukegan during 2019, including separate prosecutions for “stolen vehicle,” “burglary” and “escape,” and the details we reviewed online suggest that he had failed to comply with conditions for release. As for Ms. Williams, she was the sole defendant in a May 2019 “criminal trespass” that was ultimately not prosecuted (Lake Co. Circuit Court case #19CM00001381.) We know of no other record. But her “flame up my car” comment leaves us wondering.

To be sure, retrospective vision is one-hundred percent. Things could always have been handled better. Yet from the perspectives of the craftspersons who were saddled with the initial burden – meaning, the cops – each encounter posed a substantial risk to themselves, their colleagues, and innocent citizens. Unruly folks running around with knives or guns is never a good thing. And although no weapon was involved, check out the Waukegan pursuit clip. Sixteen seconds in, Ms. Williams blew a stop sign. Consider what might have happened had there been an oncoming vehicle in the cross street.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Still, was deadly force necessary? Shooting someone dead is an inherently repulsive notion that seems acceptable only under the most pressing of circumstances, when innocent lives are at risk and no feasible alternatives are in hand. And even when a shooting seems justifiable, can we take steps to avoid a repeat? Over the years our Strategy and Tactics and Compliance and Force sections have discussed a wide variety of practices intended to keep cops and citizens (yes, the naughty and the nice) from hurting one another, or worse. Of course, special resources may be called for. And there will always be issues with human temperament and citizens’ disposition to comply.

Our next post will bring such notions forward and apply them to each incident. In the meantime, please share your thoughts, and we’ll include them – anonymously, of course – in Part II. Until then, stay safe!

FOR UPDATES SEE PART II

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Acting? Or Re-acting? San Antonio Blues What Were They Thinking? (I) (II) Backing Off

A Partner in Every Sense When Must Cops Shoot? (II) Speed Kills De-Escalation

A Stitch in Time Making Time

Posted 10/21/20

L.A. WANTS “CAHOOTS.” BUT WHICH “CAHOOTS”?

Some politicians demand that officers keep away from “minor, non-violent” crimes

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. “Ideology Trumps Reason” and “A Conflicted Mission” blamed ideological quarrels for hobbling America’s ability to regulate its borders and control the pandemic. Here we turn to ideology’s insidious effect on crime control, as politicians capitalize on the social movement inspired by the death of George Floyd to push half-baked plans that would replace police officers with civilians.

For an example we turn to Los Angeles, where the City Council recently approved a proposal by its “Ad Hoc Committee on Police Reform” to establish “an unarmed model of crisis response.” As presently written, the measure would dispatch civilian teams instead of cops to “non-violent” 9-1-1 calls that “do not involve serious criminal activity” and have at least one of six “social services components”: mental health, substance abuse, suicide threats, behavioral distress, conflict resolution, and welfare checks.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

Approved by unanimous vote on October 14, the move was endorsed the very next day by none other than…LAPD!

The Los Angeles Police Department fully supports the City Council's actions today to establish responsible alternatives to respond to nonviolent calls that currently fall to the Department to handle. For far too long the men and women of the Department have been asked to respond to calls from our community that would be more effectively addressed by others.

So how does George Floyd fit in? Although he’s not mentioned in the actual motion, Mr. Floyd is prominently featured in an extensive report prepared by the Council’s legislative analyst:

Following the nationwide protests over the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, calls for a reduced role of law enforcement in nonviolent calls has been reiterated. The need for alternative unarmed models of crisis response has grown out of concerns related to the increased rates of arrest and use of force by law enforcement against individuals dealing with mental illness, persons experiencing homelessness, or persons of color. Armed response has been noted to be incompatible with healthcare needs or the need for other services, including service for the unhoused community.

Analyst Andy Galan isn’t out on a limb. On the very day the motion passed, its most prominent signatory, former council president Herb Wesson, Jr. argued that George Floyd would still be alive and well had civilians handled the situation instead of cops:

Calling the police on George Floyd about an alleged counterfeit $20 bill ended his life. If he had been met with unarmed, trained specialists for the nonviolent crime he was accused of, George Floyd would be turning 47 years old today. This plan will save lives.

Is he right? Might non-cops have done better? Here’s a partial transcript of the 9-1-1 call:

Caller: Um someone comes our store and give us fake bills and we realize it before he left the store, and we ran back outside, they was sitting on their car. We tell them to give us their phone, put their (inaudible) thing back and everything and he was also drunk and everything and return to give us our cigarettes back and so he can, so he can go home but he doesn’t want to do that, and he’s sitting on his car cause he is awfully drunk and he’s not in control of himself.

Mr. Wesson suggests that Mr. Floyd met all three conditions of the proposed model. His behavior was not (at first) violent. And assuming that stealing cigarettes is no big deal, neither was there any “serious criminal activity.” As for that “social service need,” the complainant reported that Mr. Floyd was “not in control of himself.” Check, check, check.

Alas, it’s only after the fact that one often learns “the rest of the story.” As a chronic drug user with a criminal record that includes armed robbery, Mr. Floyd was hardly a good candidate for civilian intervention. Watch the video. His odd, unruly behavior led the first cop with whom he tangled to conclude, probably correctly, that the small-potatoes thief was in the throes of excited delirium. Really, had Mr. Floyd complied instead of fought, that hard-headed senior officer we criticized wouldn’t have entered the picture and things could have ended peaceably.

No, guns and badges aren’t always necessary. Yet when a shopkeeper calls and complains they’ve just been swindled (Mr. Floyd copped some smokes with a fake twenty) and the suspect’s still around, dispatching civilians, and only civilians, seems a stretch. Gaining compliance from someone who’s been bad isn’t always easy. Even “minor” evildoers might have a substantial criminal record. Or maybe a warrant. Seemingly trivial, non-violent offending is potentially fraught with peril, and as your blogger has personally experienced, situations can morph from “minor” to potentially lethal in an instant. At the bottom of our list (though not necessarily in terms of its importance) 9-1-1 callers might feel slighted should they be denied a uniformed police presence.

Considering the negatives, one can’t imagine that any law enforcement agency would endorse handing off response to “minor” crimes to civilians. That’s not to say that mental-health teams can’t be useful. LAPD has long fielded SMART teams that include specially-trained police officers and a mental health clinician. They’re used to supplement beat cops in select, highly-charged situations that could easily turn out poorly. Far more often, though, officers tangle with homeless and/or mentally ill persons who don’t require the intense, specialized services of a SMART team but whose shenanigans could tie things up for extended periods. It’s for such situations, we assume, that the chief would welcome a civilian response.

That’s where Eugene’s “CAHOOTS” initiative comes in. It’s the model the city council recommended for adoption in L.A. Here’s another extract from the analyst’s report:

CAHOOTS…teams consist of a medic (a nurse, paramedic, or EMT) and a crisis worker…Responders are able to provide aid related to crisis counseling, suicide prevention, assessment, intervention, conflict resolution and mediation, grief and loss counseling, substance abuse, housing crisis, first-aid and non-emergency medical care, resource connection and referrals, and transportation to services.

Sounds great, right? But there’s a Devil in the details. Read on (italics ours):

The CAHOOTS response staff are not armed and do not perform any law enforcement duties. If a request for service involves a crime, potentially hostile individual, or potentially dangerous situation, the call is referred to the EPD.

Oops. Here’s how an Oregon CAHOOTS team member described its protocol (italics ours):

The calls that come in to the police non-emergency number and/or through the 911 system, if they have a strong behavioral health component, if there are calls that do not seem to require law enforcement because they don't involve a legal issue or some kind of extreme threat of violence or risk to the person, the individual or others, then they will route those to our team….

Police-citizen encounters have become grist for a mill of ideologically-driven solutions that overlook the complexities and uncertainties of the police workplace. George Floyd is but one example. Our Use of Force and Conduct and Ethics sections have many others. Say, the tragic case of Rayshard Brooks, the 27-year old Atlanta man who was shot dead after he fired at a cop with the Taser he grabbed from the officer’s partner. That incident, which happened in June, began with a call from a local Wendy’s complaining that a driver was asleep and blocking the drive-through lane. (Incidentally, that’s not even a crime.) The encounter began amicably. But when the seemingly pleasant man failed a field sobriety test and realized he was being arrested for drunk driving he went ballistic and a vicious struggle ensued. (Click here for the videos.)

It turns out that just like Mr. Floyd, Mr. Brooks had a history of violence and was on felony probation. Oops.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Back to L.A., where the Council’s incarnation of CAHOOTS sits on Mayor Eric Garcetti’s desk. Hizzoner once opined that Mr. Floyd was “murdered in cold blood,” so one figures that he also hankers for change. But given the realities of the streets – and the need to keep retailers and 9-1-1 callers happy – we suspect that the mayor will artfully massage things so that cops continue to be dispatched to “minor, non-violent” crimes. That, in any event, was obviously what Police Chief Michel Moore expected when he endorsed Oregon’s version of Cahoots.

Of course, the City Council would have to swallow its collective pride. Thing is, council members aren’t appointed – they’re elected. Los Angeles is a big place with a complex socioeconomic mix. Lots of residents have expressed a desire for change, and they hold the power of the vote. So we’ll see.

UPDATES (scroll)

4/29/25 Founded in 1989, Eugene, Oregon’s “Cahoots” program, which partnered police with medics and mental health specialists, became a model for like teams around the U.S. Alas, the relationship between Eugene’s cops and civilian crisis responders soured when the latter aligned with the “defund the police” movement. So “Cahoots” is out in Eugene. But it apparently remains active in adjoining Springfield.

7/17/24 An academic study of programs in Albuquerque, Atlanta, Houston and Harris County that divert 9-1-1 calls for non-criminal events and mental health crises from uniformed police to civilian responders revealed that this approach can be very effective. However, while working cops support the alternative response model, concerns by higher-level officials about personal risks to civilian responders, and of criticism by citizens who expect cops to show up, has slowed the programs’ expansion.

4/8/24 Three LAPD Divisions have begun testing the use of trained, unarmed civilians to handle nonviolent mental health-related calls. Modeled on “Cahoots,” the program is presently handling twenty percent of situations that involve neither weapons nor threats. It’s hoped that using specialists can free up officers for emergencies and avoid the “spiraling” effects that often accompany police intervention. (See below update)

3/2/23 This time it’s the cops who want others to step in. Chronic understaffing has led LAPD’s union to propose that calls about panhandling, illegal vending, peeing on the sidewalk and such be handed off to trained civilians. Ditto non-violent mental health episodes. But with traffic deaths up, police aren’t willing to give up traffic enforcement. L.A.’s City Council is reportedly taking the proposal seriously. (See above update)

8/5/22 With crime and “quality of life” violations still higher than pre-pandemic, BART, San Francisco’s transit system, uses uniformed civilian “Transit Ambassadors” and “Crisis Intervention Specialists” to conduct “welfare contacts” with homeless persons, the mentally ill and riders suffering from drug overdoses. They work in teams and with transit police to tamp down “quality of life” issues. While they’re said to be effective, their numbers are few, and one rider says he hardly ever sees them. BART website

5/11/22 Four Illinois cities – Peoria, Springfield, East St. Louis and Waukegan – will be receiving State funds to implement “co-responder” programs that partner social workers with police, creating teams that respond to mental-health emergencies and offer solutions other than arrest. Peoria’s police chief praises the initiative as part of a “new era of policing.” Chicago began a similar program last year.