|

Posted 8/4/18

POLICE SLOWDOWNS (PART II)

Cops can’t fix what ails America’s inner cities – and shouldn’t try

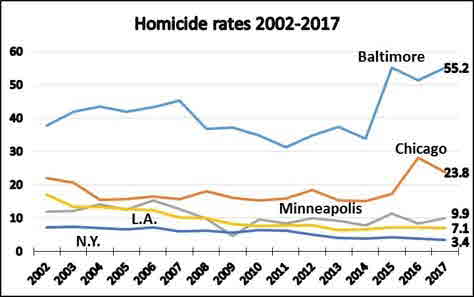

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Part I concluded that sharp, purposeful reductions in discretionary police-citizen encounters probably increased violent crime in Baltimore, Chicago and Minneapolis. Here we’ll start by considering the effects of work actions in two supposedly safer places: New York City and Los Angeles.

There are few better laboratories for assessing the effects of reducing officer activity than New York City, whose famous stop-and-frisk campaign dates back to the early 2000’s. As we reported in “Location, Location, Location” its lifespan coincided with a plunge in the city’s murder rate, which fell from 7.3 in 2002 to 3.9 in 2014.

Glance at the chart, which displays data from NYPD and the UCR. Clearly, stop-and-frisk had become a very big part of being a cop. Officers made more than six-hundred eight-five thousand stops in 2011 (685,724, to be exact). We picked that year as a starting point because that’s when adverse court decisions started coming in (for an in-depth account grab a coffee and click here.) Still, the program continued, and there were a robust 532,911 stops in 2012. But in August 2013 a Federal judge ruled that NYPD’s stop-and-frisk program violated citizens’ constitutional rights. Activity instantly plunged, and the year ended with “only” 191,851 stops. Then the bottom fell out. Stop-and-frisks receded to 45,787 in 2014, 22,563 in 2015, 12,404 in 2016 and 11,629 in 2017.

Click here for the complete collection of conduct and ethics essays

It wasn’t just stop-and-frisks. Productivity was being impacted by other issues, most notably officer displeasure with Mayor Bill de Blasio, who openly blamed cops for the serious rift with the minority community caused by the tragic July 2014 police killing of Eric Garner. Then things got worse. That December an angry ex-con shot and killed NYPD officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu as they sat in their patrol car. Officers quickly attributed his deranged act to the hostile anti-cop atmosphere supposedly being fostered by City Hall, then expressed their displeasure by going on a modified “strike”. According to NYPD statistics reviewed by the New York Post, arrests during December 2014 were down by sixty-six percent when compared to a year earlier, while tickets and the like plunged more than ninety percent. Although the magnitude of the slowdown soon receded, its effects reportedly persisted well into 2015.

On the whole, did less vigorous policing cause crime to increase? Look at the chart again. During 2011-2013 murders and stops declined at about the same rate. On its face that seems consistent with views expressed by some of the more “liberal” outlets, which concluded that doing less actually reduced crime – at least, of the reported kind (click here and here). But in 2014 the downtrend in killings markedly slowed, and in 2015, with stop-and-frisk on the ropes and officers angry at Hizzoner, murders increased. A study recently summarized on the NIJ Crime Solutions website concluded that, all in all, stop-and-frisk did play a role in reducing crime:

Overall, Weisburd and colleagues (2015)* found that Stop, Question, and Frisk (SQF) was associated with statistically significant decreases in the probability of nontraffic-related crime (including assault, drug-related crimes, weapon-related crimes, and theft) occurring at the street segment level in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Staten Island…SQFs did not have a statistically significant impact on nontraffic-related crime in Manhattan or Queens.”

* David Weisburd, Alese Wooditch, Sarit Weisburd and Sue–Ming Yang, “Do Stop, Question, and Frisk Practices Deter Crime?” Criminology and Public Policy, 15(1):31–55 (2015).

Stop-and-frisk campaigns reportedly reduced crime in other places. For example, check out Lowell, Mass. and Philadelphia. However, our views on the practice are mixed, and we’ll have more to say about it later. For now let’s move on to our last city, El Pueblo de Nuestra Senora, La Reina de Los Angeles:

L.A.’s murder rate initially followed the New York pattern, plunging from 17.1 in 2002 to 6.5 in 2013. But L.A.’s tick-up has been considerably more substantial. That concerned the Los Angeles Times, which reported that arrests paradoxically decreased by twenty-five percent between 2013 and 2015. “Field interviews” (the term includes stop-and-frisks) also supposedly dropped, and 154,000 fewer citations were written in 2015 than in 2014. Unfortunately, the Times didn’t post its actual numbers on the web. Our tally, which uses data from the UCR and the LAPD website, indicates that arrests declined 23 percent between 2014-2017, a period during which murders increased about six percent.

According to the Times, officers conceded that they had slowed down on purpose. Their reasons included public criticism of police overreach, lower staffing levels, and the enactment of Proposition 47, which reduced many crimes to misdemeanors. And while the lessened activity led some public officials to fret, some observers thought that doing less might be a good thing:

If police are more cautious about making arrests that might be controversial, making arrests that might elicit protests, then that is a victory. We want them to begin to check themselves.

Contrasting his vision of “modern policing” with the bad old days, when doing a good job was all about making lots of stops, searches and arrests, then-Chief Charlie Beck heartily agreed:

The only thing we cared about was how many arrests we made. I don't want them to care about that. I want them to care about how safe their community is and how healthy it is.

Well, that’s fine. But it doesn’t address the fact that twenty-one more human beings were murdered in 2015 than in 2014. Was the slowdown (or whatever one chooses to call it) responsible? While a definitive answer is out of reach, concerns that holding back might have cost innocent lives can’t be easily dismissed.

Other than police activity, what enforcement-related variables can affect the incidence of crime? A frequently mentioned factor is police staffing, usually measured as number of officers per 1,000 population. Here is a chart based on data from the UCR:

LAPD staffing has always been on the low end. Its officer rate per thousand, though, held steady during the period in question. So did the rate for every other community in our example except Baltimore, where the officer rate steadily declined while homicides went way up (see Part I).

Forget cops. What about the economy?

This graph, which uses poverty data from the Census, indicate that the three high-crime burg’s from Part I – Baltimore, Chicago and Minneapolis – have more poverty than the lower-crime communities of Los Angeles and New York. That’s consistent with the poverty > crime hypothesis. On the other hand, within-city differences during the observed period seem slight. So blaming these fluctuations for observable changes in crime is probably out of reach.

Back to stop-and-frisk. Is aggressive policing a good thing? Not even Crime Solutions would go that far. After all, it’s well known that New York City’s stop-and-frisk debacle, which we explored in “Too Much of a Good Thing?” and “Good Guy, Bad Guy, Black Guy (Part II)”, was brought on by a wildly overzealous program that wound up generating massive numbers of “false positives”:

[During 2003-2013] NYPD stopped nearly six times as many blacks (2,885,857) as whites (492,391). Officers frisked 1,644,938 blacks (57 percent) and 211,728 whites (43 percent). About 49,348 blacks (3 percent) and 8,469 whites (4 percent) were caught with weapons or contraband. In other words, more than one and one-half million blacks were searched and caught with…nothing.

Keep in mind that aggressive policing doesn’t happen in Beverly Hills. It happens in poor areas, because that’s where violent crime takes its worst toll. NYPD officers most often frisked persons of color because they tended to reside in the economically deprived, high-crime areas that the well-intentioned but ill-fated policing campaign was meant to transform. These graphs illustrate the conundrum:

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

In the end, turning to police for solutions to festering social problems is lose-lose. There are legal, practical and moral limits to what cops can or should be asked to accomplish. Saying that it’s a “matter of balance” is too glib. Given the uncertainties of street encounters and variabilities in resources, skills and officer and citizen temperament, calibrating aggressive practices so that they avoid causing offense or serious harm is out of reach. It can’t be done.

Correcting fundamental social problems isn’t up to the police: it’s a job for society. Police Issues is neither Red nor Blue, but when President Trump offered Charlotte’s denizens a “New Deal for Black America” that would sharply increase public investment in the inner cities, we cheered. Here’s an extract from his speech:

Our job is to make life more comfortable for the African-American parent who wants their kids to be able to safely walk the streets. Or the senior citizen waiting for a bus, or the young child walking home from school. For every one violent protester, there are a hundred moms and dads and kids on the same city block who just want to be able to sleep safely at night.

Those beautiful sentiments – that promise – was conveyed nearly two years ago. America’s neglected inner-city residents are still waiting. And so are we.

UPDATES (scroll)

3/18/19 In the NY Times Magazine, an in-depth look at how Freddy Gray affected policing in Baltimore’s violent neighborhoods, and not just for the better: “Back then, the claims were of overly aggressive policing; now residents were pleading for police officers to get out of their cars, to earn their pay — to protect them.”

1/26/19 A piece in the L.A. Times criticizes LAPD for an intensive car stop campaign it began in 2015, mostly in South Los Angeles, where it stops black motorists at a rate twice their share of the population.

9/11/18 According to a NY Times Magazine piece, student learning is most influenced by factors outside of school control: “family educational background, the effects of poverty or segregation on children, exposure to stress from gun violence or abuse and how often students change schools, owing to homelessness or other upheavals.” RAND study

8/20/18 In an op-ed entitled “Police Aren’t the Solution to Chicago’s Violence,” activist Tamar Manasseh calls for a concerted program of public investment: “Instead of spending more money on the police and surveillance technologies, it’s time to invest in our public schools, in job creation and in training programs...”

8/9/18 At least seventy four persons were injured by gunfire during Chicago’s worst weekend in more than two years. So far twelve have died, and there have been no arrests. Most shootings were attributed to gangs. These, a detective said, are always hard to solve: “it’s a dangerous thing to be a murder witness in the neighborhood where the murders are taking place.” Meanwhile, an article in the Christian Science Monitor reports that intensive attention to one hard-hit Chicago neighborhood, including job training, therapy and an active community-police partnership has brought violence way down.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Massacres, in Slow-Mo Full Stop Ahead The Usual Victims Third, Fourth and Fifth Chances

A Conflicted Mission Scapegoat (I) (II) A Workplace Without Pity Driven to Fail Be Careful (I) (II)

The Blame Game Why do Cops Lie? Why do Cops Succeed? Good Guy, Bad Guy II

Is it Always About Race? Intended or Not, a Very Rough Ride Location, Location, Location

Is Trump Right About the Inner Cities? Does Race Matter? (I) A Very Hot Summer

Liars Figure Too Much of a Good Thing What Should it Take to be Hired?

Posted 7/22/18

POLICE SLOWDOWNS (PART I)

Bedeviled by scolding, cops hold back. What happens then?

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Here’s a headline from the July 12, 2018 edition of USA Today: “Baltimore police stopped noticing crime after Freddie Gray's death. A wave of killings followed.” As our readers know, Freddie Gray was the 25-year old Baltimore man who died bouncing around the interior of a prisoner transport van in April 2015. His death led to waves of protests and, most unusually, the prompt (and ultimately unsuccessful) prosecution of the six cops involved. It also spurred DOJ to open an investigation into Baltimore PD, and particularly of “pedestrian stops, vehicle stops, and arrests from January 2010 to May 2015.” Baltimore ultimately entered into a consent decree requiring, among other things, “robust supervisory review…to ensure that officers apply proper standards when taking these actions.”

Our purpose here is to examine how police respond to public slapdowns. And it seems that in Baltimore, and elsewhere, cops reacted in a way that may have further compromised public safety. USA Today’s review of Baltimore police records reveal that self-initiated officer activity – “car stops, drug stops and street encounters” – fell sharply right after the officers were charged, then stayed down:

Where once it was common for officers to conduct hundreds of car stops, drug stops and street encounters every day, on May 4, 2015, three days after city prosecutors announced that they had filed charges against six officers over Gray’s death, the number fell to just 79. The average number of incidents police reported themselves dropped from an average of 460 a day in March to 225 a day in June of that year….By the end of last year, it was lower still.

Click here for the complete collection of conduct and ethics essays

Baltimore’s interim chief, Gary Tuggle, readily acknowledged the downturn in activity. “In all candor, officers are not as aggressive as they once were, pre-2015.” But he tried to give his department’s less enthusiastic approach a positive spin:

We don’t want officers going out, grabbing people out of corners, beating them up and putting them in jail. We want officers engaging folks at every level. And if somebody needs to be arrested, arrest them. But we also want officers to be smart about how they do that.

Commissioner Tuggle’s comments (they neatly summarize DOJ’s recommendations) were apparently taken to heart by his employees. And as they began carefully picking their fights, violence soared. According to the UCR, Baltimore’s 2014 violent crime rate was 1338.5 per 100,000 pop., an improvement of about four and one-half percent over the 2013 rate of 1401.2. But in 2015 the rate increased fifteen percent, ending at 1535.9. In 2016 it jumped another sixteen percent, to 1780.4.

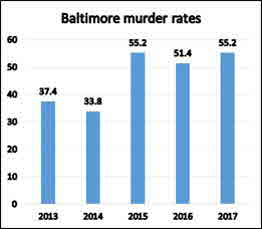

Full stop. Our confidence in the accuracy of the violent crime index is low. As we discussed in “Liars Figure,” police departments including Baltimore have often finagled the numbers. Murder, though, seems less subject to manipulation. And in Baltimore, its trend proved similar. Between 2013 and 2014 killings declined from 233 to 211, a rate decrease of ten percent. But 2015, the year of the incident, closed out with 344 homicides; the rate, 55.2, was sixty-three percent higher than in 2014. In 2016 the raw number (318) and rate receded a bit. But then things got intolerable. 2017’s toll of 343 killings not only set a local record but confirmed Baltimore as the second most murderous community above 250,000 population in the U.S.

Did the less vigorous, post-Gray approach “cause” murder to increase? Your blogger’s only a half-baked methodologist, so he’s reluctant to opine. As they say, correlation is not (necessarily) causation. Was the coincidence between police vigor and crime just a quirk? No, said emeritus professor of public policy Donald Norris, formerly of the University of Maryland’s Baltimore campus:

Immediately upon the riot, policing changed in Baltimore, and it changed very dramatically. The outcome of that change in policing has been a lot more crime in Baltimore, especially murders, and people are getting away with those murders.

On October 20, 2014 Chicago PD officer Jason Van Dyke shot and killed Laquan McDonald, a mentally troubled 17-year old black youth who had been wielding a knife. Van Dyke said the youth had threatened him with the weapon, and his account was supported by colleagues. One year later the other shoe dropped. In November 2015, after much cajoling, Chicago finally released the police video. It depicted a stunning scene; far from menacing the cops, McDonald was actually walking away when he was repeatedly shot. Protests quickly engulfed the city, and officer Van Dyke, who as it turns out had been the subject of many complaints, was charged with murder. In 2016 seven other officers were recommended for firing, and one year after that three were criminally charged with obstructing justice.

Chicago officials had little choice. As soon as the video came out, they asked DOJ to step in. Instantly, yet another “pattern and practices” investigation was underway. Its final report, issued in January 2017, concluded that Chicago officers “use unnecessary and unreasonable force in violation of the Constitution with frequency, and that unconstitutional force has been historically tolerated by CPD.” Among the many observations was that aggressive tactics had led citizens in higher-crime districts to view police as an “occupying force”:

At one COMPSTAT meeting we observed, officers were told to go out and make a lot of car stops because vehicles are involved in shootings. There was no discussion about, or apparent consideration of, whether such a tactic was an effective use of police resources to identify possible shooters, or of the negative impact it could have on police-community relations.

City officials expressed deep support for the report’s conclusions. Mayor Rahm Emanuel called it “a moment of truth for the city.” Lori E. Lightfoot, president of the Chicago Police Board, promised to demand “that the reforms happen.” One can imagine how cops felt. But how did they respond?.

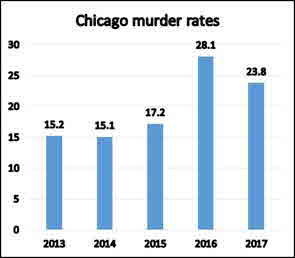

This graph, which depicts UCR data, indicates that Chicago’s murder rate jumped sixty-three percent in 2016. Slowdown believers would attribute that to the video’s release in late 2015. ABC News’ data-rich website FiveThirtyEight took a close look. Published five months after the video came out, its rich, extensive analysis of Chicago crime and police activity data revealed that between December 2015 (the month following the video’s release) and March 2016 there were 175 murders and about 675 shootings not resulting in death, forty-eight and seventy-three percent more than during the same period a year earlier. This “severe spike in gun violence” was accompanied by significant declines in arrest rates for homicide (down forty-eight percent) and nonfatal shootings (down sixty-nine percent.) FiveThirtyEight concluded that clearly supported the notion of cause and effect: This graph, which depicts UCR data, indicates that Chicago’s murder rate jumped sixty-three percent in 2016. Slowdown believers would attribute that to the video’s release in late 2015. ABC News’ data-rich website FiveThirtyEight took a close look. Published five months after the video came out, its rich, extensive analysis of Chicago crime and police activity data revealed that between December 2015 (the month following the video’s release) and March 2016 there were 175 murders and about 675 shootings not resulting in death, forty-eight and seventy-three percent more than during the same period a year earlier. This “severe spike in gun violence” was accompanied by significant declines in arrest rates for homicide (down forty-eight percent) and nonfatal shootings (down sixty-nine percent.) FiveThirtyEight concluded that clearly supported the notion of cause and effect:

Even though crime statistics can see a good amount of variation from year to year and from month to month, this spike in gun violence is statistically significant, and the falling arrest numbers suggest real changes in the process of policing in Chicago since the video’s release.

So what changed? Roseanna Ander, of the University of Chicago Crime Lab, suggested that the post-video release atmosphere made officers hesitant about exercising discretion, thus less likely to act proactively. “Certainly they’ll respond to 911 calls…but if you have a group of guys on the corner and you think you have probable cause to stop them and see if one of them has a gun, you’re probably not going to do that.” On the other hand, while a Chicago PD spokesperson agreed that proactivity took a hit, he blamed the downturn on increased paperwork.

Paperwork? A recently released study, “What Caused the 2016 Chicago Homicide Spike? An Empirical Examination of the ‘ACLU Effect’ and the Role of Stop and Frisks in Preventing Gun Violence,” assessed the impact of various factors that could have led to Chicago’s surge in violence. It ultimately blamed changes in stop-and-frisk practices. In late 2015, to settle an ACLU lawsuit, Chicago began requiring that officers thoroughly document each stop-and-frisk on elaborate, highly time-consuming forms. As one might expect, the encounters promptly declined by eighty percent, and the slowdown continued at least through 2016. According to the authors, onerous paperwork was at the root of the steep decrease. As one might expect, the ACLU sharply disagreed (it called the study “junk science.”)

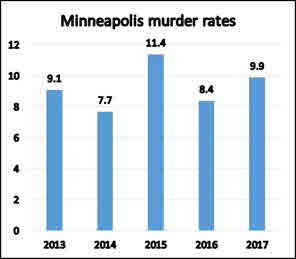

Baltimore and Chicago are two of the better documented examples of the supposedly criminogenic effects of a police “slowdown.” But cops have slowed down elsewhere. Consider Minneapolis, which occupies the next position on our introductory graph. During a roll call two years ago a police inspector reportedly “erupted” and accused officers of being “cowards” for participating in a slowdown. To be sure, some things had slowed. During January-May 2016, citywide arrests were off by twenty-eight percent, and stop-and-frisks by thirty-two percent compared to the same period in 2015. Shootings, though, skyrocketed, increasing from forty to seventy-four, a deplorable eighty-five percent.

Why had Minneapolis’ finest slowed down? Observers point to several factors, most importantly the severe public reaction to the November 2015 police killing of Jamar Clark, an unarmed black man who allegedly reached for a Minneapolis cop’s gun during a struggle. Months later police were back on the hot seat, this time over the detention at gunpoint of a citizen driving through an area where shots were reportedly fired. (He turned out to be a department store executive and was eventually let go.)

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

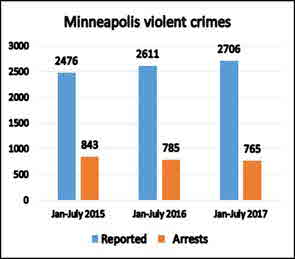

Minneapolis’ murder rates don’t clearly support the notion that a police slowdown directly increased violence. While the homicide rate jumped fifty-four percent between 2014-2015, it receded somewhat in 2016, the year following Jamar Clark’s killing. (Murder then went up again.) So we broadened the inquiry to include incidence and arrest data for Part I violent crime: murder, aggravated assault, forcible rape and robbery. Equivalent January – July periods for 2015, 2016 and 2017 were compared with online Minneapolis PD data. (These were selected because second-half 2017 numbers are not yet in. Also keep in mind that they report raw numbers, not rates.) What we found supports the Inspector’s concern that the slowdown fostered crime: As violence increased, arrests consistently dropped. Coincidentally – or not – both trends came in at 9.3 percent.

Well, time has come for your blogger to “slow down.” Part II will discuss what happened in two supposedly safer places, Los Angeles and New York City, which also experienced slowdowns. We’ll bring in confounding factors such as variations in police staffing, and discuss what happens when police get too “enthusiastic.” Then throwing caution to the wind, we’ll offer our own, startling recommendations. And as always, stay tuned!

UPDATES (scroll)

12/9/24 An analysis of traffic stops by New Jersey State Troopers between 2009-2021 concluded that members of racial minorities were far more likely to be stopped, cited, searched, subjected to the use of force, and arrested. According to the New York Times, this finding, which was made public in July 2023, caused traffic enforcement to plummet by 81 percent during the following eight months, and “coincided with an almost immediate uptick in motor vehicle crashes.”

5/30/24 An in-depth probe by the New York Times and The Baltimore Banner concludes that Baltimore suffers from “the worst drug crisis” ever seen in a major U.S. city. Between 2018-2022, its fatal overdose rate of 170/100,000 pop., which produced nearly 6,000 deaths, was twice that of Knoxville, the runner-up. Undermined by politics, with cops distracted by reactions to the Freddie Gray fiasco, chronic gun violence and COVID-19, Baltimore’s innovative public-health approach fell by the wayside. But Mayor Brandon Scott disagrees. He blames a lack of resources and greedy pharmaceutical companies that flooded the city with prescription pills. And they’re being sued.

5/5/23 Violence-ridden Minneapolis is beset by three street gangs: the “Lows,” the “Highs”, and the “Bloods”. On May 3 DOJ unsealed indictments charging thirty members of the “Highs” and the “Bloods” with a RICO conspiracy to commit murder and robbery and to traffic in drugs. Fifteen additional members are charged with Federal gun and drug violations. A like indictment naming the “Lows” is anticipated. DOJ news release

4/22/22 In 2017 Baltimore PD was placed under Federal monitoring because of the death of Freddie Gray. Five years later, the Justice Department praised the agency’s shift to “problem-oriented policing” and its adoption of regulations on the use of force, prisoner transport (what killed Mr. Gray) and officer conduct. During the next several months Baltimore must demonstrate that the officers are “consistently and effectively following” the new rules.

4/19/22 Former Chicago cop Jason Van Dyke was released from prison in February after serving about half his six-year term for the murder of Laquan McDonald. Federal authorities announced they would not file civil rights charges as proof is lacking that Van Dyke purposely sought to deprive Mr. McDonald of his Constitutional rights and didn’t act from “mistake, fear, negligence, or bad judgment.” Meanwhile the Federal consent decree that was imposed after the killing remains in effect. In the latest report, the monitor says that officer training and the foot chase policy have both improved, but warns that at CPD “quantity” still seems to override “quality” and that true community engagement is still lacking.

12/16/20 In 2012 an FBI sting led to the arrest and conviction of former Chicago police Sgt. Ronald Watts and Officer Kallatt Mohammed, who during a “decade of corruption” extorted drug dealers and residents of a housing complex and allegedly pressed phony charges. Their activities led to the exoneration of fifteen persons in 2017 alone. So far eighty persons convicted through their testimony have had their charges dismissed, with the most recent eight coming yesterday.

12/2/20 A Chicago police sergeant and three officers had appealed their firing for allegedly covering up the actions of officer Jason Van Dyke, who was convicted of murdering Laquan McDonald. A judge recently upheld the discharge of Sgt. Stephen Frank and officer Daphne Sebastian for misleading investigators with “false statements or reports.” Decisions about the other two officers are pending.

3/18/19 In the NY Times Magazine, an in-depth look at how Freddy Gray affected policing in Baltimore’s violent neighborhoods, and not just for the better: “Back then, the claims were of overly aggressive policing; now residents were pleading for police officers to get out of their cars, to earn their pay — to protect them.”

1/17/19 A Chicago judge acquitted three officers of conspiring to obstruct justice by giving false accounts that justified officer Jason Van Dyke’s shooting of Laquan McDonald. Two, Van Dyke’s partner and an officer who investigated the incident, have resigned.

10/5/18 Chicago jurors convicted officer Jason Van Dyke of second-degree murder and sixteen counts of aggravated battery with a firearm. He faces a minimum of six years imprisonment. His lawyer bemoaned the conviction and said it would make cops fearful of doing their jobs. But a sign-waving crowd awaiting the verdict outside City Hall rejoiced.

8/8/18 At least seventy-four persons were injured by gunfire during Chicago’s worst weekend in more than two years. So far twelve have died, and there have been no arrests. Most shootings were attributed to gangs. These, as an unnamed detective said, are always hard to solve: “it’s a dangerous thing to be a murder witness in the neighborhood where the murders are taking place.”

8/20/18 In an op-ed entitled “Police Aren’t the Solution to Chicago’s Violence,” activist Tamar Manasseh calls for a concerted program of public investment: “Instead of spending more money on the police and surveillance technologies, it’s time to invest in our public schools, in job creation and in training programs...”

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Massacres, in Slow-Mo Full Stop Ahead The Usual Victims Third, Fourth and Fifth Chances

Is Crime Really Down? It Depends... Urban Ship Scapegoat (I) A Workplace Without Pity

Driven to Fail Be Careful What You Brag About (I) (II) The Blame Game Why do Cops Lie?

Why do Cops Succeed? Good Guy, Bad Guy, Black Guy II Is it Always About Race?

Intended or Not, a Very Rough Ride Location, Location, Location Does Race Matter? (I)

Liars Figure What Should it Take to be Hired?

Posted 2/10/18

WHY DO COPS LIE?

Often, for the same reasons as their managers

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. As a retired Fed who investigated gun trafficking, your blogger was dismayed to learn about the implosion of Baltimore PD’s Gun Trace Task Force. After pleading guilty to racketeering charges, three former members of that once-celebrated team were recently back in Federal court, testifying against colleagues who deny being involved in a years-long scheme that involved lying about probable cause, extorting suspects and stealing large sums of cash. [See 9/14/22 update]

Meanwhile a once-promising law enforcement career unraveled in a New York courtroom. In a stunning verdict, jurors unanimously agreed that NYPD Detective Kevin Desormeau lied to a grand jury when he testified that he and his partner observed someone selling drugs. That falsehood, which was used to justify a body search that did turn up contraband, was exposed by a surveillance camera that faithfully recorded how the cops really encountered the man. Desormeau and his colleague – she was convicted of a lesser crime but acquitted by the judge – aren’t done; both are pending trial for lying in a case about illegal gun possession.

This isn’t the first time that NYPD’s finest have been accused of fudging. In its 1995 report on police corruption, the city’s Mollen Commission warned that police lying was leading judges and jurors to hold “skeptical views of police testimony, which potentially could result in the dismissal of those criminal cases where police officers were the sole prosecution witnesses.” (p. 68)

Click here for the complete collection of conduct and ethics essays

Nearly two decades later, little had apparently changed. A New York judge who presided at the bench trial of a detective who allegedly planted drugs admitted he was unnerved by evidence of widespread police wrongdoing: “I thought I was not na´ve. But even this court was shocked, not only by the seeming pervasive scope of misconduct but even more distressingly by the seeming casualness by which such conduct is employed.”

Yes, he found the cop guilty. And that too seemed quickly forgotten. Three years later, a report by NYC’s Civilian Complaint Review Board concluded that false statements by police were on the increase. Their findings became gist for a major story by New York Public Radio. It was troublingly entitled “The Hard Truth About Cops Who Lie.”

What’s been called “testilying” brings us to the front door of yet another NYPD sleuth, Detective Louis Scarcella. An acclaimed long-time homicide investigator with a once-enviable track record, his “propensity to embellish or fabricate statements” (that’s what a judge said in 2015) has so far led to the reversal of eight convictions, most recently last July, when prosecutors accused him of lying about what a witness said. Scarcella’s reputation first took a turn for the worse in 2013 when a man he helped convict was freed after serving twenty-three years. “What’s important to me is that this fellow should not be in prison one day longer,” said the Brooklyn D.A., whose investigators had concluded that the exoneree’s protests that he was “framed” by police might actually be true. Now there’s even talk of vacating a conviction not because of what Scarcella did in a case, but simply because his reputation for being loose with the facts wasn’t disclosed to the defense.

According to the Knapp Commission, police corruption comes in two flavors. “Meat Eaters” aggressively use their badge to line their pockets, while “grass eaters” confine themselves to lesser sins, say, accepting a tenner to forego writing a ticket. Still, one could hope that after the twentieth century’s deplorable legacy of police misconduct – New York, Chicago, Detroit and Los Angeles come to mind – America’s cops finally turned the corner. Indeed, Baltimore-like episodes of out-and-out, self-serving venality, which seem an integral part of old-time policing, are now relatively rare. Neither Detective Desormeau nor his partner reportedly extorted anyone. As for Detective Scarcella, he’s not been accused of any crimes, only of doing shoddy work.

Taking the long view, things seem a lot better. Most cops now make a pretty decent living, and hiring standards have definitely been upgraded. Still, given the many examples of serious misconduct, there’s obviously reason to worry. Selfishness, after all, is embedded in the human DNA. Maybe we don’t recognize much of “the new police corruption” because the causes and forms have transformed. Maybe we simply don’t want to know.

Let’s return to the New York Times account about Detective Desormeau:

At his trial, prosecutors suggested that Detective Desormeau had decided that making lots of arrests was the route to glory in the New York Police Department, which was why he decided to falsify evidence.

Desormeau’s lawyer was clearly hoping that his client’s untruths, which he characterized during closing arguments as “just a little white lie,” would be justified by the arrestee’s unsavory past, which reportedly includes prison time for killing two men. But the implication that the partners were pursuing a greater social good was challenged by prosecutors, who accused the pair of being “only interested in advancing their careers by getting high arrest statistics and getting promoted.”

Before that pesky surveillance camera intervened, Desormeau had a decidedly bright future. In the Compstat-besotted, number-counting NYPD, a department where officers are expected to meet arrest quotas (and, until the Feds intervened, make as many stop-and-frisks as possible), and detectives are expected to make lots of arrests, a medal of valor holder with more than 350 career arrests would definitely be on track for big things.

Let’s not just pick on NYPD. In November 2012 two LAPD partners, both in the middle of promising careers, were convicted of planting drugs and lying about it in court. Again, a surveillance video saved the day, catching the pair as they allegedly manipulated evidence while engaged in a telling verbal exchange. “Be creative in your writing,” said one. “Oh yeah, don't worry” replied the other.

We’re not arguing that all cops are potentially evil. For most, public service is undoubtedly the main motivator. On the other hand, officers are people. Offering temptations such as favored assignments or promotions will inevitably encourage some to take shortcuts. “Confirmation bias,” that all-too-human tendency to quickly resolve ambiguities in a way that furthers one’s own interests and beliefs, has led to everything from the needless use of force to “helping” witnesses identify the person whom a cop “knows” must have done it.

In every line of work incentives must be carefully managed so that employee “wants” don’t steer the ship. That’s especially true in policing, where the consequences of reckless, hasty or ill-informed decisions can easily prove catastrophic. But we can’t expect officers to toe the line when their agency’s foundation has been compromised by morally unsound practices such as ticket and arrest quotas. This unfortunate but well-known management approach, which is intended to raise “productivity,” once drove an angry New York City cop to secretly tape his superiors, with predictable consequences. And consider the seemingly contradictory but equally entrenched practice of downgrading serious crimes – say, by pressuring officers to reclassify aggravated assaults to simple assaults – so that departments can take credit for falling crime rates. (For a recent take check out the “Be Careful What You Brag About” two-parter, below.)

Why set arrest quotas? Why fudge crime statistics? Chiefs also have bosses. Mayors and city managers control department purse strings and select their chiefs. If manipulating stat’s can make things look good for everybody, well…

As law enforcement professionals (that’s what your blogger, retired or not, still considers himself) we like to think that we’re different. Yet the picture we’ve laid out seems like it came straight out of “Three Billboards.” (If you haven’t seen it, go!) What’s more, it’s not just the cops. Deception is an integral aspect of our legal system, where advantage is everything and truth-telling is considered hopelessly naiive. Imagine how long a civil attorney would last if she was always fully transparent with opposing parties. Or what would happen to a defense lawyer who demanded that his clients tell police the whole truth, and nothing but.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Ah, back to policing. Being a cop is, at heart, a craft. Craftspersons are supposed to pay exquisite attention to detail and be committed to the excellence of their product. Yet as the painter Robert Williams once lamented, “you’ve got legions of people who have lost craftsmanship. They’ve lost the romance of what they’re doing. The virtuosity.” (Los Angeles Times Magazine, June 5, 2005, p. 7.) How can we get law enforcement back on track? Let’s skip over controls. Here’s an approach that usually goes unconsidered: craftsmanship. To honor their true and only “client” – the public – police executives must forget about numbers and get back to emphasizing quality. Offering unwavering support for doing things as they ought to be done would go a long way towards helping officers navigate the moral dilemmas and resist the unholy pressures that have tarnished their highly demanding vocation. Their craft.

By the way, if you’re hankering for an in-depth assessment of the quantity/quality conundrum (it likens police work to, of all things, woodcarving) click here. Also let us know what you think. Use the “contact” link and we’ll post your comments. And thanks!

UPDATES (scroll)

12/13/24 Roger Golubski, a 72-year old former Kansas City Police detective, recently committed suicide as he was to go on trial for sexually assaulting Black women during his decades as a cop. (Golubski is White.) That was soon followed by the release of Dominique Moore and Cedric Warren, who were imprisoned for a 2009 double murder investigated by the now-discredited cop. But Judge Aaron Roberts denied that the dismissal of charges was about Golubski. Instead, it was based on prosecutors’ concealment of the fact that a key witness against Moore and Warren was schizophrenic, and that his accounts of what took place had shifted.

10/10/24 Former Houston P.D. detective Gerald Goines will have to serve at least thirty years on a pair of 60-year murder terms he just received over the deaths of two occupants of a home that was raided by his colleagues during a no-knock entry. Not knowing it was the police, the occupants opened fire and wounded four officers during the ensuing shootout. Goines, who lied about a narcotics buy to get the search warrant, was responsible for George Floyd’s 2004 conviction for selling crack cocaine. (See below update)

9/26/24 In 2019 then-Houston P.D. detective Gerald Goines got a no-knock search warrant by falsely claiming that an informant bought narcotics at a residence. And when officers, thinking the warrant legit, stormed the premises, they were met by gunfire. Four officers were wounded, and their return fire killed both occupants, a 59-year old man and his 58-year old wife. A jury just convicted ex-cop Goines of their murder. (Goines, it turns out, had once arrested George Floyd on drug charges.) (See 8/8/22 and above updates)

11/21/23 Former NYPD Detective Louis Scarcella, who plied his trade thirty-plus years ago, had a “rep” as someone who could solve the toughest murder cases. Problem is, his “propensity to embellish or fabricate statements” (that’s how a judge put it) ultimately led to the exoneration of more than a dozen inmates, many of whom had been locked up for decades. Settling their lawsuits has so far cost the city and state more than $100 million. Hired in 1973, he retired in 1999. And no, he was never punished.

8/12/23 A public defender accused Orange County, Calif. Sheriff Det. Matthew LeFlore of switching 17 grams of meth seized elsewhere into the drug possession case against Ace Kuumeaaloha Kelley. And lab records seem to back that up. Evidence also suggests that Sgt. Arthur Tiscareno “manipulated records” to help conceal the switch. Prosecutors have now dropped charges against Kelley. LeFlore, who is reportedly under investigation but remains on the job, is also accused of an alleged prior switch of evidence to support gun possession charges against another accused. (See 5/16/23 update)

5/26/23 A report by Chicago’s Inspector General blasts the police department for thumbing its nose at a 2019 Federal consent decree by continuing to employ scores of police officers who lied during criminal investigations. But the city’s Police Board states that twenty-one officers have been fired for lying during the past five years. Before then, some were given leniency, but nonetheless received three-year suspensions. A city law requiring that officers who lie be fired has been recommended.

5/16/23 Two years ago the Orange County, Calif. Grand Jury excoriated sheriff’s deputies for failing to book evidence, then lying about it in their reports. One of the accused, Det. Matthew LeFlore, reportedly left seized drugs and ammunition in a pair of boots and labeled it “free”. A defense lawyer now accuses Det. LeFlore of transferring seized drugs from one case to another so as to support charges against his client, Ace Kuumeaaloha Kelley. And lab records seemingly back his allegation. (See 7/5/21, 8/11/21 and 8/12/23 updates)

2/1/23 Two weeks into the criminal trial of notorious veteran NYPD narcotics detective Joseph Franco, an irate judge dismissed the case because prosecutors repeatedly failed to share crucial evidence with the defense. In 2019 ex-cop Franco’s alleged litany of misdeeds led to a perjury indictment. He was fired the next year and hundreds of criminal cases in which he participated were tossed. His own case has now been dismissed “with prejudice,” meaning it cannot be refiled. And his prosecutor has been demoted.

1/20/23 Manhattan’s criminal court is the site of the felony trial of disgraced former NYPD narcotics detective Joseph Franco, whose litany of alleged lies has led to the dismissal of more than one-hundred cases. But his attorney argues that the five persons whom Franco is charged with lying about had, by their own admissions, been dealing drugs. If Franco provided incorrect accounts of what he saw, and where, these were simply “mistakes” caused by an “imprecise process,” and definitely not crimes (see 9/8/22, 4/26/21 and 2/1/23 updates).

11/2/22 Concerns about the credibility of seven suspended members of a D.C. anti-gun squad will probably lead to the dismissal of “dozens of felony gun and drug cases.” Their bonafides came under suspicion after it turned out that the officers had been seizing guns but not making arrests, supposedly because they lacked proof as to who possessed the guns. It now turns out that body camera video from those encounters is inconsistent with their reports.

9/14/22 A half-million dollars plus. That’s what Baltimore is paying out to Darnell Earl, whom the city’s corrupt gun trafficking task force arrested and sent to jail in 2015. Within a couple of years, though, a Federal inquiry revealed that the unit “routinely violated people’s rights and stole drugs and money using the authority of their badge,” and three of its cops wound up in Federal prison. So far the city’s paid out $15.48 million to settle the unit’s misdeeds. And it’s still not done.

9/8/22 Brooklyn’s D.A. is moving to dismiss 378 convictions, including 47 felonies and 331 misdemeanors, resulting from arrests made during 1999-2017 by thirteen officers who were later discredited for assorted misconduct. Former cop Jerry Bowens, who supplied drugs to informers and murdered his girlfriend, was involved in 130 of these cases. Sixty were connected to former cop Eddie Martins, who pled guilty to bribery. Ninety additional convictions tied to disgraced former detective Joseph Franco were dismissed last year (see 1/20/23 update).

8/8/22 Lying on affidavits to obtain search warrants goes well beyond the Breonna Taylor case, says the New York Times. In Houston, an officer awaits trial for falsely obtaining a narcotics search warrant in 2019 that led to a shootout in which four officers were wounded and two occupants were killed. In that case Det. Gerald Goines claimed an informant made a buy, but no such person seems to exist. (Det. Goines is responsible for George Floyd’s 2004 conviction for selling crack cocaine. See George Floyd post, 10/6/21, 9/26/24 and 10/10/24 updates.)

7/16/22 Despite “shaky” witness ID’s and “factual inconsistencies,” disgraced former NYPD detective Louis Scarcella and a partner allegedly used “threats, lies, sleep deprivation and physical violence” to get three teens, Vincent Ellerbe, James Irons and Thomas Malik, to confess to a 1995 arson/murder. On July 15, on motion of the D.A., who said the confessions were coerced, a judge vacated the convictions. Irons and Malik were released (Ellerbe was paroled in 2020.) Each had served more than two decades.

10/6/21 George Floyd’s criminal record in Houston includes a 2004 felony conviction for selling crack cocaine. He pled guilty and served ten months. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles has now recommended that he be retroactively pardoned for that crime. Its investigating detective, Gerald Goines, awaits trial for murder relating to a botched drug raid, and “more than 160 drug convictions” resulting from his work have been dismissed because of concerns that he lied to obtain search warrants. For a review of Houston policing and its intersection with the life of George Floyd, click here.

8/11/21 According to L.A. County Sheriff’s detective Jason McGinty, a productive search turned up guns and narcotics in a suspect’s home. But the deputy in charge wanted more. He asked McGinty to report that he saw a suspect handle one of the guns. McGinty refused. His colleague and another detective nonetheless included that false account in their reports, and it was used for prosecution. When McGinty realized it, he turned his colleagues in. They were recently indicted for perjury. (see 5/16/23 update)

7/5/21 In 2018 the Orange County sheriff’s department learned that for years many deputies falsely reported booking evidence when in fact they delayed doing so for protracted periods. One year later the problem became known by prosecutors and defense lawyers. Dozens of cases were dismissed and several deputies were prosecuted for lying on reports. According to a recent Grand Jury report, booking evidence is time-consuming and takes away time from making arrests, an activity on which deputies “placed a higher value.” (See 5/16/23 update)

4/26/21 NYPD detective Joseph E. Franco, a veteran undercover narc, had a sterling record. Until 2019, that is, when videos showed that drug sales he “witnessed” didn’t happen. He was charged with perjury and awaits trial. Meanwhile prosecutors, having “lost faith” in the disgraced cop’s “credibility,” are moving to dismiss about ninety convictions that resulted from his work (see 1/20/23 update).

12/16/20 In 2012 an FBI sting led to the arrest and conviction of former Chicago police Sgt. Ronald Watts and Officer Kallatt Mohammed, who during a “decade of corruption” extorted drug dealers and residents of a housing complex and allegedly pressed phony charges. Their activities led to the exoneration of fifteen persons in 2017 alone. So far eighty persons convicted through their testimony have had their charges dismissed, with the most recent eight coming yesterday.

7/10/20 A massive criminal complaint charges three officers in LAPD’s Metro unit with falsifying official records by falsely claiming that persons they had stopped were gang members or associates.

2/13/20 Lawsuits and challenges by two dozen individuals who allege that they were wrongly entered into Cal Gangs has led LAPD to remove them from the statewide gang database. Police insist that they’re properly using the system. But the State AG has opened an investigation.

1/9/20 A number of LAPD officers (reportedly, more than a dozen) assigned to its stop-and-frisk campaign have been removed from duty for purposely and incorrectly portraying persons they stopped as gang members, thus inflating their productivity and minimizing errors. NY Times

9/14/19 In July a New York City judge accused officers who found a gun in a car of lying when they justified their search by saying they had smelled pot. She also said the problem is widespread. Some officers agree. According to the Times, the practice increased after NYPD, under public pressure, cut back on stop-and-frisks.

4/1/19 Under the watchful glare of five exonerees he allegedly framed, Louis Scarcella is back in court, answering questions about current prisoner Nelson Cruz. Yes, the retired NYPD detective insisted, he did his job right. No, Mr. Cruz was not framed.

3/9/19 Houston PD’s chief accused veteran narcotics detective Gerald Goines of lying to get a search warrant that led to the fatal shooting of two citizens and the wounding of five officers. An internal inquiry contradicted Goines’ assertion that he had informers make buys at the home.

11/26/18 As of 10/1/18 U.S. immigration court judges must complete 700 cases per year to earn a “satisfactory” rating. From 560-699 earns “needs improvement,” and less than 560 is “unsatisfactory.” Intended to reduce backlogs, the move is “raising concern among judges and attorneys that decisions may be unfairly rushed.” But a Federal exec noted that “using metrics to evaluate performance is neither novel nor unique...” For an op-ed from a judge who resigned click here.

9/13/18 Three NYPD sergeants, two detectives and two officers have been arrested and more than three-dozen civilians have been charged for operating a criminal enterprise that included a string of brothels and a numbers game. Their boss? A retired NYPD vice detective.

8/9/18 In California and other states D.A.’s lack full access to police personnel records. That means that unless agencies volunteer information, prosecutors may not know, and defense lawyers won’t learn, that officer witnesses such as an L.A. County deputy have a truth-blemished past. A court case about that (no. S243855) is winding its way through the California Supreme Court.

3/23/18 Investigations by the New York Times found that NYPD officers probably gave false testimony at least twenty-five times since 2015. Their motives included making stops and searches “legal” and creating enough evidence to assure convictions. NYPD also imposed discipline in only two out of eighty-one occasions where civilian panels concluded that officers had lied. To reduce “testilying” a writer suggested that detectives wear body cameras, police ease access to surveillance video, and courts become more actively involved.

2/28/18 Another NYPD detective has been arrested for lying. Federal prosecutors allege that Det. Michael Foder, 41, fabricated photospreads to “prove” that a witness identified two carjack suspects. Det. Foder awaits trial, while the suspects have pled guilty to an unrelated crime.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES AND REPORTS

The Craft of Policing Production and Craftsmanship in Police Narcotics Enforcement

RELATED POSTS

Damn the Evidence - Full Speed Ahead! A Recipe for Disaster Informed and Lethal

Police Slowdowns (I) (II) Fewer Can be Better Be Careful (I) (II) Accidentally on Purpose

Guilty Until Proven Innocent Good Guy, Bad Guy, Black Guy (II) Orange is the New Brown

Cooking the Books Quantity, Quality and the NYPD The Numbers Game NYPD Blue

Too Much of a Good Thing Liars Figure Lying: The Gift That Keeps on Giving

|