|

Posted 6/9/18

FEWER CAN BE BETTER

Murder clearances have declined. Should we worry?

www.law.umich.edu

Note to readers referred from Texas website: As its subtitle clearly states, this essay suggests that problems with wrongful conviction may have have affected murder clearance rates. This essay does not address whether problems with wrongful conviction may have affected clearance rates for other crimes. Also, this author has never had any connection, other than his nickname, with the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Murder has always been the most frequently cleared serious crime. In the mid-1970s police were reportedly solving an impressive eight out of ten homicides. But a downtrend apparently took hold. Clearances fell to 72 percent in 1980, 67 percent in 1991, and 63.1 percent in 2000.

In 2008, with clearances stuck in the mid-sixties, the Feds stepped in. Four years later BJA released “Homicide Process Mapping: Best Practices for Increasing Homicide Clearances.” Produced by the IACP and the Institute for Intergovernmental Research, the 54-page report set out promising approaches to homicide investigation in seven jurisdictions of varying size: Baltimore County PD, Denver PD, Houston PD, Jacksonville S.O., Richmond PD, Sacramento County S.O. and San Diego PD. Why were these agencies chosen? In 2011, when the overall murder clearance rate was 64.8 percent, each enjoyed a rate exceeding 80 percent.

A sense of urgency permeates the report. Here’s the BJS director’s opening message:

One homicide victim is one too many. Yet we also understand the challenging and quite complex nature of homicide investigations. Homicide, homicide investigations, clearance rates, and productive communication with the public are all critical concerns for law enforcement and communities nationwide. And despite recent across-the-board improvements in homicide clearance rates, we know that we can do better.

Click here for the complete collection of wrongful conviction essays

And here’s the first paragraph of the executive summary:

Since 1990, the number of homicides committed in the United States has dropped over 30 percent. While this is a positive trend, it is somewhat counterbalanced by another trend: in the mid-1970s, the average homicide clearance rate in the United States was around 80 percent. Today, that number has dropped to 65 percent—hence, more offenders are literally getting away with murder.

We won’t belabor the findings. As one might expect, resources get prominent attention. There’s an emphasis on technology and information. Agencies are strongly encouraged to include forensic specialists and crime analysts in homicide teams. Data is said to have reshaped the detective’s task: “the investigator must be an information manager who can coordinate and integrate information from a wide range of sources to drive the investigation forward.”

Then what happened? Clearances kept going down, falling to 59.4 in 2016. Of course, many homicides are “cleared” over time. Still, considering that the murder rate is presently about half that of the crack-addled nineties (1991=24,703 murders, rate 9.8; 1996=17,250 murders, rate 5.3) the persistent decline in solution rates seems puzzling.

During the early morning hours of April 17, 1994 a woman was stabbed to death in her Jacksonville County apartment. At the time the only other occupant was her brother-in-law, Chad Heins. He said he found her body when he awakened that morning. No physical or other evidence implicated Heins. However, he was convicted based on the testimony of two jailhouse informants who said he confessed. Heins drew a life term. In time the Innocence Project got involved. Between 2003-2006 a sequence of DNA tests confirmed that semen and skin residue from fingernail scrapings belonged to the same, unidentified third party. More damningly, it turned out that officers and prosecutors apparently kept quiet about a bloody fingerprint found at the scene that did not match Heins. He was exonerated in 2007 after serving thirteen years.

A happy ending? Not exactly. Eight years later Heins was convicted in a tax fraud scheme hatched by a former cellmate. Citing the time Heins did for a murder he didn’t commit, the judge went easy and sentenced him to a year and a day.

Heins’ investigation was conducted by the Jacksonville sheriff’s office, one of the seven contributors to the BJA report. A glance through the National Registry of Exonerations turned up wrongful convictions for murder and other crimes of violence (alas, without a known ironic aftermath) involving each of the other six police agencies. For example, the 1991 conviction of Jeffrey Cox, a Richmond resident who got life plus fifty for murder. Although police had two suspects in mind, they added Cox to a photo lineup after one of the suspects brought up his name. And that’s whom two neighbors identified. What police and prosecutors didn’t let on was that one of the witnesses was a multi-convicted felon, while the other had charges that would be dropped in exchange for his testimony. And that a composite sketch of the killer didn’t resemble Cox. And that a recovered hair didn’t match. What finally set things right was when a witness came forward and said he was told by one of the two original suspects that they committed the killing and that Cox wasn’t involved. That took eleven years, but hey, who’s counting?

Your blogger, a retired ATF agent, spent a career pursuing gun traffickers. When he and his colleagues caught them in the act, the quantity and quality of evidence was terrific. And when investigations didn’t work out, they turned their attention elsewhere. After all, there were always plenty of good leads to chase.

That pattern applies to all “victimless” crime, including narcotics offenses. Unproductive inquiries can be easily dropped. And when everything lines up and suspects get caught, say, illegally transferring a load of guns or drugs, the evidence is indisputable. Evildoers literally convict themselves.

That’s something that homicide detectives can only dream about. Like most cops, they work reactively, collecting what evidence they can after the fact. While they enjoy high status and comparatively ample resources, their mission is inherently stressful. We mentioned that in 2016 the homicide clearance rate was a seemingly robust 59.4 percent. Of course, if six in ten murders are promptly solved, that means four in ten languish. Pursuing these “whodunits” can consume prodigious amounts of shoe leather and laboratory time, and all with no guarantee of success. Yet one can’t simply give up. Most detectives wouldn’t want to. And even if they did, their managers would likely balk. After all, what would the public think? The victim’s family?

Killers are seldom caught “in the act”. Yet the level of certainty required for conviction – beyond a reasonable doubt – is the same for all crimes. In reactive policing such as homicide investigation, where reaching this threshold depends on the availability of witnesses and physical evidence, pressures to produce results may drive officers to use illegitimate means, and particularly when the heat’s on. Here are some relevant extracts from prior posts:

- External and self-induced pressures to solve heinous crimes can lead even the best intentioned investigators to set aside doubts and interpret information in a light most favorable to a prompt resolution. (“Guilty Until Proven Innocent”)

- “Probable cause” can be an elastic concept, and all the more so when police are under pressure to solve a high-profile crime. (“Rush to Judgment, Part II”)

- Pressures to solve serious crimes can cause the theory of a crime to form prematurely, leading authorities to uncritically gather evidence that is consistent with that notion regardless of its merit or plausibility. (“House of Cards”)

- As cases move through the system subtle pressures from police and prosecutors can make witnesses overconfident, turning a tentative “maybe” into a definite “that’s the one!” (“Can We Outlaw Wrongful Convictions? Part II)

- …pressures to solve violent crimes can lead agencies and investigators to prematurely narrow their focus. Concentrating investigative resources on a single target inevitably produces a lot of information. As facts and circumstances accumulate, some can be used to construct a theory of the case that excludes other suspects, while what’s inconsistent is discarded or ignored. That’s how a “house of cards” gets built. (“The Ten Deadly Sins”)

We could go on, but the reader undoubtedly gets the picture. One would think that the mighty Feds are well aware of these issues. Yet clearance rates are the only measure of success that 54-page report mentions. Nothing is said about dreadful mistakes like convicting the innocent. Same for a “Morning Edition” piece that gave prominent play to the shallow musings of a self-anointed “expert”:

Homicide detectives say the public doesn't realize that clearing murders has become harder in recent decades. Vernon Geberth, a retired, self-described NYPD "murder cop" who wrote the definitive manual on solving homicides, says standards for charging someone are higher now — too high, in his opinion. He thinks prosecutors nowadays demand that police deliver "open-and-shut cases" that will lead to quick plea bargains.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

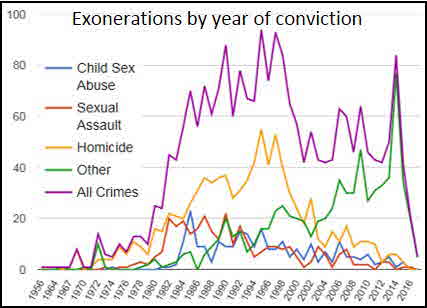

So what about that decline in clearance rates? With all the attention that’s been given to the scourge of wrongful conviction, from Dallas County D.A.’s pioneering conviction integrity unit, since replicated in many other jurisdictions, to the Innocence Project and its numerous clones, to the near daily stream of headlines and breathless exposÚs about exonerations, the need for caution has apparently sunk in.

Our expectations (and apparently, NPR’s) for solving murders were set too high. Being more careful likely lowered the numbers. No matter. Sometimes fewer really is better.

UPDATES (scroll)

3/14/25 In 1996 Brittany Holberg was a 23-year old sex worker when she visited an elderly customer at his Amarillo, TX residence. Holberg later claimed that he started beating her, and she killed him in self-defense. She was arrested, and at her trial a cellmate testified that she admitted killing him for his money. Holberg was convicted and got the death penalty. But her lawyers weren’t told that the cellmate was a paid police informant. That just led a Federal appeals court to toss the conviction and send the matter back to a lower court. Holberg has served more than a quarter century. For now, she remains in custody.

12/6/23 Writing in the New York Times, a data analyst warns that clearance rates for serious crimes have fallen to new lows. Although clearances have been on a decades-long downtrend, in 2022 police reported solving “only 37 percent of violent crimes, just over half of murders and non-negligent manslaughters and only 12 percent of property crimes.” Blame is placed on hiring issues, which have led to shortfalls in investigative resources, and public attitudes, which soured on the cops post-George Floyd.

9/10/22 L.A. County’s progressively-led D.A.’s office has joined Jesse Gonzales’ bid for a retrial on his conviction and death sentence for murdering a plainclothes sheriff’s deputy in 1979. His defense - that he thought the deputy was a rival gang member - was challenged by jailhouse informant William Acker, who testified that Gonzales told him that was a lie. But Acker, along with other jailhouse informers, has since lost credibility, and the D.A. feels that a conviction on 2nd. degree murder

would be more appropriate.

11/29/21 There have been 130 murders in the Bronx through 11/21. That’s nearly thirty percent more than in 2020 and sixty-five percent more than in 2019. That increase in caseload alone poses a major challenge. There are other obstacles. Residents of troubled neighborhoods fear cooperating with police. Many locations lack sufficient surveillance cameras, and those in place can’t see through masks. Clearances are substantially down. But about sixty-two percent of murders are presently being solved.

10/8/21 An analysis by the Council on Criminal Justice revealed that fifty percent of homicides were cleared in 2020. That’s five percent fewer than in 2019 and “the largest one-year decline since 1989.” Homicide clearances have been going down since the 1970’s; 82 percent were cleared in 1976.

1/3/18 A detailed sentinel review of a murder conviction in Maryland that led to an innocent man’s imprisonment for sixteen years blamed eight factors, including sloppy investigative and witness identification procedures and a poor defense. Nothing was mentioned about the pressures that detectives face to clear homicides. (Click here for a recent post that discusses the sentinel approach.)

11/28/18 Two articles in The Crime Report (click here and here) starkly warn of a “cold case crisis” in solving homicides. What can help? “Commitment, manpower and funds” and, for smaller agencies, participating in a task force. Concerns about miscarriage of justice are not mentioned.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

When Does Evidence Suffice? Damn the Evidence - Full Speed Ahead! A Victim of Circumstance

Cops Aren’t Free Agents Is Your Uncle a Serial Killer? Why do Cops Lie?

Guilty Until Proven Innocent The “Witches” of West Memphis Rush to Judgment II

No End in Sight Baby Steps Aren’t Enough House of Cards Can We Outlaw Wrongful Convictions II

Miscarriages of Justice: A Roadmap The Ten Deadly Sins Near Misses

RELATED ARTICLES

Production and Craftsmanship in Police Narcotics Enforcement The Craft of Policing

|