|

Posted 5/6/18

IS YOUR UNCLE A SERIAL KILLER?

Police scour DNA databanks for the kin of unidentified suspects

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. When a Sacramento-based task force recently arrested the long-sought “Golden State Killer” it wasn’t the first time that “familial” DNA has been used to find a mass murderer. “The Killers of L.A.” discussed the case of Lonnie Franklin, “The Grim Sleeper,” who was convicted in 2016 of committing ten murders and one attempt between 1985 and 2007. Franklin was tracked down with the help of California’s Familial DNA Search Program. Established in 2008, it offers an opportunity, when crime scene DNA does not match an existing profile in the state databank, to identify possible family members of an as-yet unidentified suspect.

More about that shortly. First, let’s briefly review how crime scene DNA matching works. (For a more complete account, click here.) DNA, our chemical template, resides in 23 pairs of chromosomes we inherit from our parents. Twenty-two pairs are “autosomal,” meaning gender-independent, and one pair is the sex chromosome (females have two X chromosomes and males have one X and one Y.) DNA has four “bases,” Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine and Thymine that connect in tandem. Some locations always have the same sequence. For example, in chromosome 5, at the location (“locus”) known as CSF1PO, the four unit base sequence A-G-A-T is always present.

|

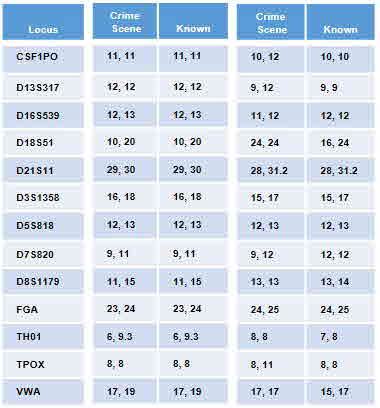

Population studies have identified autosomal DNA loci where certain base sequences called “short tandem repeats” (STR’s) repetitively appear. For example, at locus CSF1PO, A-G-A-T repeats from six to sixteen times. To determine whether DNA found at a crime scene matches that taken from a “known” person, forensic scientists focus on thirteen loci where a certain STR string is always present. When the number of repeats inherited from each parent is identical for corresponding STR’s at all thirteen loci (columns on left), examiners can testify that the probability is overwhelming that the DNA originated from the same person or an identical twin. But if there are any differences (columns on right) sorry – wrong person!

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

That’s when a “familial” approach can help. Although the Grim Sleeper’s DNA profile was not in the California databank, an inquiry in 2010, after the state began familial searches, revealed that it resembled that of a recently convicted felon. In addition, the male (Y) chromosomes closely matched, suggesting a father/son relationship. Officers learned that the convict’s father, Lonnie Franklin, lived in the area and had a long rap sheet. They then shadowed him until he discarded some pizza.

Bingo! DNA from the crust matched DNA from the crime scenes. (For a paper about the matching process and its use in various cases, including the Grim Sleeper investigation, click here.)

Every state collects DNA profiles of persons arrested or convicted of certain crimes. Federal, state and local authorities also contribute DNA profiles to the FBI’s National DNA Index System (NDIS). Of course, these databases only cover a thin slice of the population. That’s what stymied investigators pursuing California’s notorious “Golden State Killer.” Crime scene DNA tied a single individual to twelve murders, forty-five rapes and over 120 residential burglaries between 1976 and 1986, but a familial search of official DNA repositories yielded nothing worthwhile. (Click here, here and here for detailed accounts about the investigation in the Los Angeles Times.)

Frustrated cops broadened their quest to include consumer genealogical databases. Those such as 23andMe and AncestryDNA require that users submit a vial of saliva and pay a fee. Cops lacked the killer’s spit. So they turned to GEDmatch. Unlike the others, it accepts user-uploaded DNA profiles. To build family trees GEDmatch capitalizes on the fact that differences between human DNA are mostly in single base pairs at certain loci. In its hunt for relatives its software counts how many of these pairs, known as SNP’s, match between samples. The more that do, the closer the relation. (For a thorough discussion click here.)

GEDmatch and other sites deny they knowingly helped police. So it was left to authorities to impersonate the Golden State Killer and supply crime scene DNA in the required format. This process generated a family tree of about 1,000 persons whose familial relationships traced back to the 1800s. Criteria such as physical characteristics and places of residence gradually whittled the list down. Four months later police identified a possible suspect, Joseph James DeAngelo, 72. Officers followed him and gathered discarded DNA.

Bingo! A perfect STR match.

Familial DNA is nothing new. Its place of origin, the U.K., has used it in violent crime investigations since 2002 with considerable success. An early application in the U.S. was in the case of Dennis Rader, the notorious “BTK Killer.” In 2005, after a decades-long investigation suggested he was the one, analysts found a close match between crime scene DNA and the DNA of his daughter, who had been hospitalized for a medical procedure. Investigators collared Rader. He promptly confessed.

Thanks to lots of shoe leather, though, Rader was already a suspect. A recent example of a blind hit is the case of Gilbert Chavarria, the “San Diego Creeper,” who forced his way into a string of homes and sexually assaulted children. After a couple of frustrating years police finally identified him through a familial search of the California databse, which identified a close relative. Chavarria was convicted in January. (For more success stories click here.)

In 2007 Colorado became the first state to allow familial searching of its state DNA databank. Since then the practice has spread to eleven additional states: Arizona, California, Florida, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming. That still leaves a lot of holdouts. Why? One reason is that familial searching provokes considerable angst among civil libertarians, who object because it disproportionately affects members of minority groups, who are overrepresented in arrests and convictions. Indeed, that’s reportedly why Maryland and the District of Columbia legally ban the practice altogether. And it’s why the Legal Aid Society of New York has sued to block its use:

This is dangerous. It’s an end-run around the legislative branch. Clearly there’s a racial bias to who is policed. Innocent people, largely poor and in communities of color, will now become a suspect group of folks.

There are other concerns. In 2014 familial DNA led Idaho police to accuse a filmmaker of a 1996 murder. Michael Usry was targeted through his father’s DNA, which authorities had obtained from a genealogical website with a court order. Although Usry was ultimately cleared – the match was very close, but not perfect – the experience put him and his family through a miserable time.

Familial searching is intrusive. It can also prove very expensive. A Federally-sponsored study revealed that state laboratories that perform familial searches usually restrict them to crimes of violence. While these labs also conveyed worries about civil liberties, legal issues and the accuracy of findings, the one universally-cited concern was cost. This might be the principal reason why several states that use familial searching have rules strictly limiting its use. For example, California restricts familial searching of its database to crimes with “critical public safety implications” where an agency “has pursued all other reasonable and viable investigative leads, including DNA profile comparison(s) to suspect reference samples, with negative results.”

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Even when state labs are willing, localities may not be up to the task. Familial searches yield an inherently ambiguous forensic work-product that requires extensive follow-up investigation. That responsibility often falls on local agencies that may lack the resources to assemble and scour family trees across multiple jurisdictions.

Still, when Grim Sleepers, Golden State Killers and their ilk get caught, it’s time to celebrate. On April 10, following a multi-year investigation, Scottsdale (AZ) police arrested Ian L. Mitcham for the grisly murder of Allison Feldman. The breakthrough came when familial DNA provided a “near match” to a prison inmate. Mitcham was his brother. While acknowledging that the technique has privacy implications, the victim’s father is planning a roadshow to encourage non-familial states to give it a go. “It’s for Allison. I hope it provides some relief to other families, like it has done to us.”

UPDATES (scroll)

7/3/25 Bryan Kohberger, a criminology PhD student at Washington State University, was identified as the killer of four University of Idaho students with the help of genetic DNA. Three years ago, Kohberger, who was unacquainted with his victims, broke into a home late at night and used a “military-style” knife he had bought online to stab them as they lay in bed. His motives are unknown. He just pled guilty, ostensibly to avoid the death penalty. Some of the victim’s relatives support the outcome; others are upset that Kohberger wasn’t required to fully confess. (See 2/27/25 and 12/31/22 updates.)

5/12/25 Las Vegas Metropolitan police have a “cold-case” detail, led by a Sergeant, that specializes in pursuing leads on unsolved, long-ago homicides. And they’ve just added a forensic genealogist to the mix. “It's amazing that we can use that technology now to go back 30-40 years later and try to solve a case” says one of the unit’s three full-time detectives. Five retired homicide investigators also work for the unit, part-time.

5/8/25 It took twenty-three years. But in 2024 Montgomery Co., MD detectives arrested Eugene Gligor for the 2001 strangulation murder of Leslie Preer, the mother of Gligor’s one-time girlfriend. His name came up when officers had an ancestry research company build a family tree using crime scene DNA. Gligor’s DNA was then obtained through a ruse in which a Customs agent left a water bottle for him to hold during an ostensible airport screening. Its DNA proved a perfect match. Gligor just pled guilty.

3/28/25 LAPD arrested Andre Cobbs in Febuary after a sex assault victim escaped from his car and took its picture - and his. But the D.A. wanted more. So detectives uploaded Cobbs’ DNA into the FBI’s nationwide CODIS system. That linked him to a decades-long spat of L.A.-area sex assaults and robberies by a knife-armed man. Some of the victims were sex workers. Cobbs, who was once charged with robbing and assaulting a sex worker, has been jailed on $1.7 million bond pending arraignment.

3/10/25 In 1995 a Virginia woman was viciously stabbed to death in her home. Her assailant’s identity remained a mystery until 2023, when a private lab used DNA to build the killer’s family tree. And shortly after police paid him a visit to ask for a cheek swab, software engineer Stephan Smerk, 53, soulfully confessed. A recovered alcoholic, he had became well educated, married, had children, and enjoyed a seemingly ideal life. Smerk recently pled guilty and just drew seventy years. As for his motive: he had none. Smerk said that he had felt compelled to kill, and was “a serial killer who’s only killed once.”

2/27/25 Bryan Kohberger, 28, is pending trial for the November 2022 stabbing deaths of four University of Idaho students. Police initially submitted DNA profiles from a knife sheath to genetic databases that openly allow law enforcement access. However, these yielded excessively weak matches. But when investigators turned to two family-tree services that supposedly don’t allow access to the police, a far stronger match was produced. Strong enough to eventually lead police to Mr. Kohberger. His lawyers now say that warrants should have been used. But so far, a judge has turned them away. (See 12/31/22 and 7/3/25 updates)

1/3/25 James Vanest was suspected from the very start. But the April 1981 beating death of Debbie Lee Miller, whose Mansfield, Ohio apartment was just above his, went unsolved for forty years. In 2021 advanced DNA techniques identified Vanest’s profile in DNA mixtures found on “numerous pieces of evidence” recovered from the scene. Detectives interviewed Vanest then, and again earlier this year. They were preparing their case when Vanest, a felon, was killed in a shootout with officers who were trying to arrest him on gun charges stemming from a recent traffic stop.

Keep going...

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

NIJ papers on familial DNA policies and practices

RELATED POSTS

Technology’s Great - Until It’s Not Fewer Can Be Better The Killers of L.A. Proceed With Caution

Beat the Odds, Go to Jail

|