|

For the State prosecution of Lane, Kueng and Thao click here

For the Federal trial of Lane, Kueng and Thao click here (for a .pdf click here)

For the State trial of Derek Chauvin click here (for a .pdf click here)

For the main essay about George Floyd, “Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job,” click here

For our video compilation that tracks the encounter with Mr. Floyd, click here

EX-COPS FACE STATE CHARGES

Chauvin’s colleagues were charged with aiding and abetting

2nd. deg. murder and 2nd. deg. manslaughter

Summary and charges Pre-trial motions Pleas and sentences

SUMMARY AND CHARGES

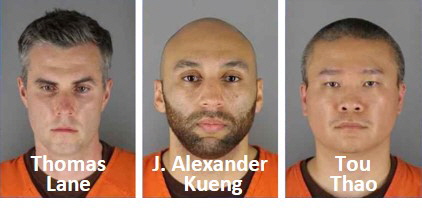

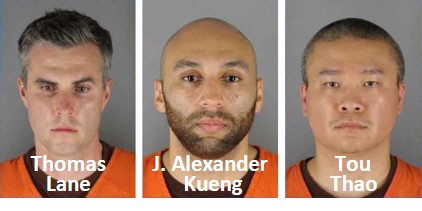

On May 25, 2020 rookies Thomas Lane and J. Alexander Kueng were working as partners. First to arrive on scene, they found Mr. Floyd in a parked car and soon got him out and to the curb (for a detailed account see “Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job.”) Veteran cops Tou Thao, with ten years on the job, and Derek Chauvin, with nineteen, arrived later.

Chauvin was convicted at a state trial of unintentional second-degree murder while committing a felony and was sentenced to 22 1/2 years. He later pled guilty to Federal civil rights charges and drew a 21-year term.

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

Lane, Kueng and Thao went to trial first on the Federal case. Each was convicted of violating Mr. Floyd’s Constitutional rights while acting “under color of law.” Sentencing is pending. Their State trial is scheduled to begin on June 13, 2022. Each is charged with violating two Minnesota criminal statutes (click here, here and here for the Complaints):

- 609.19.2(1) Aiding and abetting second-degree murder (unintentional, while committing a felony). Maximum punishment: 40 years.

- 609.205(1) Aiding and abetting second-degree manslaughter (culpable negligence creating an unreasonable risk). Maximum punishment: 10 years or $20,000 or both.

Prosecutors cited section 609.05(1), which makes aiders and abettors liable for “a crime committed by another.” But if before the crime is committed a person “abandons that purpose and makes a reasonable effort to prevent the commission of the crime” they can avoid liability.

On May 18, 2022 Lane pled guilty (see below).

PRE-TRIAL MOTIONS & THAO’S TRIAL BY JUDGE (scroll)

Thomas Lane J. Alexander Kueng Tou Thao

2/2/23 In their written closing argument, Minneapolis prosecutors emphasized that ex-MPD cop Tou Thao, an experienced officer, was besieged by spectator comments that George Floyd was in extremis and had stopped breathing, yet he kept an off-duty firefighter from stepping in to help. Thao also knew from training of the lethal risks posed by Chauvin’s persistent pressure on Floyd’s neck area, but did nothing to intervene.

2/1/23 In his stipulated closing argument, defendant Tou Thao submitted photos from the police academy that show students being instructed on applying their knees to the back of a suspect’s neck. Accordingly, he could not know that in doing so Chauvin was committing a crime. He also did not know that Mr. Floyd had stopped breathing and was without a pulse. Tao acted in accordance with his training about excited delirium and helped get Floyd an ambulance as quickly as possible, and even called again when medics didn’t promptly arrive.

1/31/22 Ex-Minneapolis cops Thomas Lane and J. Alexander Kueng pled guilty to a State charge of aiding and abetting manslaughter in the death of George Floyd; Lane in May 2021 and Kueng in October 2022. Both are serving State and Federal terms concurrently. But their former colleague Tou Thao, who was also charged with aiding and abetting manslaughter, chose to go to trial. In October 2022 he agreed to be tried on stipulated evidence presented to a judge. On January 30 prosecution and defense formally submitted a joint stipulation. A decision is expected soon.

10/21/22 Lawyers for ex-MPD cops Tou Thao and J. Alexander Kueng have filed a request for a “Supplemental Juror Questionnaire” that would ask jurors to report what they heard about the case in the media, how that affected their views of the accused and their culpability, whether they participated in George Floyd-related protests, their view about MPD officers, and whether minorities are treated fairly.

10/18/22 Two years ago the judge presiding over the forthcoming trial of ex-MPD cops J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao for aiding and abetting the murder of George Floyd ruled that jurors would remain anonymous. Defendant Kueng’s lawyer has filed an objection. He asserts that keeping juror identities secret would prejudice his client, as it “suggests to jurors that the defendant is dangerous or that the jury is in jeopardy themselves.”

10/14/22 Judge Peter Cahill’s trial management order for the forthcoming trial of former Minneapolis cops Tou Thao and J. Alexander Kueng for aiding and abetting the murder of George Floyd bars live coverage of the proceedings. Courtroom spectators are prohibited from using cell phones, while members of the media can use electronic devices, but only for taking notes.

10/6/22 As the state trial for ex-MPD cops Tou Thao and J. Alexander Kueng nears, lawyers on both sides have submitted extensive motions that seek to bar the admission of evidence. For example, the defense demands that bystanders not be allowed to testify about whether Mr. Floyd was alive or dead and, as to the latter, what its cause may have been. Prosecutors object to criticism about Chauvin’s qualifications to be a training officer and to mention of the defendant’s personal backgrounds and experiences as volunteers.

8/17/22 Morries Lester Hall was George Floyd’s front-seat passenger. Hall served notice that he will take the Fifth - refuse to testify - if called on at the State trial of former MPD cops Thao and Kueng. His testimony would have related to Floyd’s drug possession and use. Hall originally gave police a phony name as he had outstanding felony warrants for gun possession, drug possession and domestic assault.

8/16/22 Ex-Minneapolis officers Tou Thao and J. Alexander Kueng declined to plead guilty to State charges of aiding and abetting the murder of George Floyd in exchange for three-year prison terms, to run concurrently with their Federal sentences of about the same length. Accepting the offer “would be lying,” said Thao. Their State trial remains scheduled for October.

6/22/22 Based on a previous commitment to a defense lawyer, and a motion for speedy trial by the prosecution, the trial of J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao was reset to October 2022. Jury selection will begin on October 24, and opening statements are scheduled for November 7.

6/6/22 The trial of ex-MPD cops Tao and Kueng has been continued until January. Jury selection is scheduled for January 9; opening arguments for January 30. Two media rep’s, several members of Floyd’s family and of the accused and a few spectators will be allowed in the main courtroom. Two other rooms are designated for overflow. Live broadcast and the use of any electronic devices remains prohibited.

6/3/22 Citing the burden of proving that police officers committed murder, prosecutors filed a motion opposing the defendants’ demand that they strictly limit the number of expert witnesses so as to avoid the “needless presentation of cumulative evidence” of guilt. Prosecutors are particularly concerned about introducing necessary evidence about medical issues and the “reasonableness” of the force used. Bystanders should also be allowed to testify, as they can introduce videos and confirm that they did not interfere with police.

Defendant Kueng’s lawyers filed a comprehensive motion raising numerous objections with the State’s case. Among other things, they demanded that the felony-murder count be dropped, as the officers’ physical contact with Mr. Floyd was not an “assault.” Moreover, the officers did not use “deadly force”, as “putting your knees on the back of a suspect does not create a ‘substantial risk of causing, death or great bodily harm.’” Kueng’s lawyer also objects to testimony about the “duty to intervene,” as it is not a statutory obligation. Defendant Thao’s lawyers join in these arguments. They also object to the State’s attempt to disqualify several of their prospective witnesses, and particularly Steve Ijames and Dr. Shawn Pruchnicki.

5/30/22 Lawyers for Tou Thao renewed their motion for a change of venue or, in the alternative, a continuance until after the accused are sentenced for their Federal convictions. In support, they cited the Federal judge’s remarks criticizing the “disproportionate power of the prosecutor vis-à-vis the accused,” the vast publicity that attended the Federal convictions, and news reports that quoted the State’s Attorney General as “pleased Thomas Lane has accepted responsibility” by pleading guilty to the State case. There is also reference to a legal action filed by a State prosecutor who claims that she was discriminated against for being female and for disagreeing about charging Lane, Kueng and Thao.

In response, the State filed a motion opposing a change of venue. It argued that “given the realities of modern communication,” pretrial publicity is inevitable, and quoted a Supreme Court decision that held “[p]rominence does not necessarily produce prejudice, and juror impartiality...does not require ignorance.” (Skilling v. U.S., no. 08-1394) For like reasons it also opposes a continuance.

5/28/22 Arguing that “news coverage [of the George Floyd episode] was more extensive than any story in fifty years,” lawyers for J. Alexander Kueng moved for a change of venue or, in the alternative, for a year-long continuance. Their motion cites an opinion by Dr. Bryan Edelman in which he states that “the jury pool in Hennepin County has been saturated with extensive prejudicial news coverage” to such an extent that “jurors will either ignore” evidence of innocence “or make cognitive efforts to refute it.”

5/24/22 An amicus motion filed by the ACLU urges the Court to reconsider its ban and allow live audio/video coverage of the forthcoming trial. In its opinion, the combination of an A/V ban and a restriction of visitors and press to a limited overflow room violates the First Amendment. A motion for the Court’s reconsideration of its severe restriction of access to the courtroom where the trial will be held was also filed by a coalition of media companies (see 4/25 entry, below).

5/20/22 Prosecutors moved to exclude the testimony of proposed defense expert Dr. Kimberly Ann Collins. A forensic pathologist, she has written extensively about the deaths of “vulnerable populations,” including “deaths during police restraint, custody, and excited delirium.” One list of her writings includes “Natural death in the forensic setting,” “Sudden death due to asphyxia by esophageal polyp” and “Sudden unexpected death resulting from an anomalous hypoplastic coronary artery.” These and other titles suggests that she might support the theory that George Floyd’s death was caused by excited delirium and/or pre-existing medical conditions.

Should Dr. Collins testify, she will probably be asked to counter prosecution experts who essentially blamed Mr. Floyd’s death on strangulation. Defendant Kueng’s lawyer moved to require that “the actual dimensions of Mr. Floyd’s pharynx” come into play during testimony by witnesses such as Dr. Martin Tobin. (During Chauvin’s trial Dr. Tobin blamed pressure on Mr. Floyd’s neck for causing his death. See Day 9). Kueng’s lawyer also moved to prevent witnesses from testifying about “their personal ethic” or applying it to the use of force. A particular objection was raised to testimony at the Federal trial by Lt. Richard Zimmerman, MPD chief of homicide. (He condemned the accused for failing to step in as “Mr. Floyd was slowly being killed.” See Day 11.)

Defendant Thao’s lawyer moved to prevent non-expert witnesses, such as bystanders, from offering opinions about the use of force or its effects. He also moved to keep prosecutors from asking questions “that would elicit an emotional response,” of asking experts questions that go outside their area of expertise, and of having multiple experts testify about the same area.

5/13/22 Prosecutors filed a request to limit the evidence to be presented by the defense. Referencing the Federal trial, they object to much of the testimony presented by retired chief Stephen IJames, who spoke about Chauvin’s control of the scene and what officers must do when dealing with persons in excited delirium. Referencing Chauvin’s trial, they object to evidence from Dr. David Fowler, who ascribed Floyd’s death to pre-existing medical conditions. Prosecutors also sought to limit presentations by other experts on the defense list. Among them is Greg Meyer, a police tactics expert who submitted a report that seems to exculpate Lane, and two academics who study human error, Dr. Shawn Pruchnicki and Dr. Sidney Dekker.

5/12/22 Referencing the Chauvin trial, Lane’s attorneys filed a motion requesting that the Court limit the evidence to be presented by the prosecution. They object to the use of “spark of life” testimony (on Day 11 Philonise, George Floyd’s younger brother, offered personal, heartwarming comments about George Floyd’s character and mental state). They also demand that prosecutors be limited to two use-of-force experts, as their presentation of “repeated opinions” about the same issues conferred an unfair advantage. And they ask that prosecutors focus their rebuttal on responding to the defense rather than rehashing their own case.

5/5/22 Lane’s attorneys, Earl Gray and Amanda Montgomery, filed a motion for continuance and change of venue. They assert that “there is no possibility of a fair and impartial jury with the residents of Hennepin County, the politics, and public hatred of these defendants.” In an accompanying affidavit, Mr. Gray reports that he read 150 of 265 questionnaires completed by prospective jurors, and that ninety percent were “either bias[ed] against our client Thomas Lane and/or need to be excused because of hardship or being afraid of the aftermath.” What’s more, those questionnaires were completed before the Federal trial took place.

4/25/22 Trial will begin Monday, June 13. It will not be livestreamed. No electronic devices will be permitted in the main courtroom. Two media representatives may be present but can only take notes. Four members of Floyd’s family and two family members of each defendant may also be present. Audio and video feeds will be supplied to overflow courtrooms on a different floor. Those courtrooms will be available for use by media, family and the public. Media rep’s in those courtrooms can use electronic devices and post on social media.

4/8/22 Concerned that the easing of the pandemic may lead the Court to reconsider allowing live audio/video coverage of the trial, a media coalition argues against disappointing “the millions of people who viewed the Chauvin trial.” At issue is Minnesota Rule 4.02(d), which seems to require that all parties consent to live coverage of criminal trials.

4/7/22 Prosecutors declared their “strong support for audio and video coverage” of the trial. In its absence, they requested a live feed be provided for use by family members, expert witnesses and legal staff that may need to quarantine.

Prosecutors moved to severely limit the testimony of Dr. David Fowler, the main author of a report produced by the “Forensic Panel,” to matters only within his field of expertise, which they assert does not include “detailed toxicology findings, comments on Mr. Floyd’s and Defendants’ psychiatric states, and observations about how medical treatment is administered.” Such matters should only be commented on by area experts, and their proposed testimony must be promptly disclosed. (Click here for Dr. Fowler’s testimony during the Chauvin trial.)

1/19/22 Trial is continued until June 13, 2022.

1/11/22 Court rejects defendants’ motions to bar live coverage of the trial and reaffirms its commitment to allow the same audio and video coverage as it authorized for the trial of Derek Chauvin. Its reasoning, explained in the original November 4, 2020 order, was that social distancing requirements brought on by the pandemic severely limited space for spectators and the press.

9/15/21 Appearing in Federal court via video, former Minneapolis police officers Derek Chauvin, Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao pled not guilty to violating George Floyd’s civil rights. Lane, Kueng and Thao asked that to avoid undue prejudice they be tried separately from Chauvin, whom “everybody knows...was convicted of murder.” Thao’s lawyer also asked that his client, an experienced cop, be tried alone, as his defense would be inconsistent with that of rookies Lane and Kueng.

|

PLEAS AND SENTENCES

J. Alexander Kueng

On December 9, 2022 Kueng was formally sentenced to 3 1/2 years in State prison. He will serve it concurrently with the 36-month term he has been serving in Federal prison for violating Floyd’s civil rights. Including credits, he will be locked up for a total of about 2 1/2 years.

On October 24, 2022, just as jury selection was set to begin, J. Alexander Kueng pled guilty to aiding and abetting second-degree manslaughter in the death of George Floyd. He agreed to serve 3 1/2 years in prison. Charges of aiding and abetting second-degree murder were dropped. Court order

Thomas Lane

On September 21, 2022 Judge Peter Cahill imposed the agreed-upon three year State prison term on Thomas Lane, to be served concurrently with his two and one-half year Federal term. As the State term is subject to credit for good behavior, it’s expected that Lane will be released from custody in both cases in slightly more than two years.

On May 18, 2021 Lane pled guilty to Count 2, aiding and abetting 2nd. degree manslaughter. Count 1, aiding and abetting murder, was dismissed. Lane agreed to a term of 36 months imprisonment, of which he must by law complete two-thirds, to run concurrently with his Federal sentence (see below).

Tou Thao

On May 1, 2023 Hennepin County, Minnesota Judge Peter A. Cahill, acting without a jury, found Tou Thao guilty of aiding and abetting second-degree manslaughter in the killing of George Floyd. That’s the same charge to which Thomas Lane and J. Alexander Kueng pled guilty. Sentencing is pending.

On October 24, 2022, just as jury selection was set to begin, Tou Thao waived a jury trial and the right to testify. He faces one count of aiding and abetting manslaughter, and his fate will be decided by the judge based on stipulated evidence whose content is to be negotiated by both sides. Court order

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Feedback

Posted 1/21/22

EX-COPS ON FEDERAL TRIAL

Chauvin’s colleagues were tried on Federal civil rights charges

Week by week Verdict Sentencing

SUMMARY AND CHARGES

On May 7, 2021 a Federal Grand Jury indicted the four former Minneapolis police officers who arrested George Floyd for violating 18 USC 242, which forbids willfully (“intentionally, deliberately or designedly, as distinguished from an act or omission done accidentally, inadvertently, or innocently”) violating a person’s Constitutional rights while acting “under color of law.”

- Count One pertains to Derek Chauvin, the senior officer on scene.

- Count Two accuses J. Alexander Kueng, a rookie, and Tou Thao, an experienced officer with ten years on the job, of failing to stop Chauvin’s use of excessive force.

- Count Three, which brings in Thomas Lane, a rookie, accuses him and his three colleagues of failing to render aid to Mr. Floyd, thus demonstrating a “deliberate indifference to his serious medical needs”. (Click here for the indictment.)

Chauvin won’t be going to trial. In December he pled guilty to the Federal civil rights charges, admitting that he had used “unreasonable and excessive force” and did so in a “callous and wanton” manner with disregard for the likely consequences. He also pled guilty to a separate, two-count indictment that charged him with violating the rights of a 14-year old boy on Sept. 4, 2017 by using excessive force. On July 7, 2021 he was sentenced to 21 years imprisonment. “You absolutely destroyed the lives of three young officers” said Federal judge Paul Magnuson. Chauvin will have to serve nineteen years, which more than what he would have served for his 22 1/2 year State term. But Chauvin likely prefers to do his time in a Federal lock-up, and both sentences will run concurrently.

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

A Federal jury that will try Lane, Kueng and Thao was selected and seated in a single day, January 19. According to reporters, eleven of the twelve regular jurors are White, and one is Asian. Five of the alternates are also White, and one is Asian. One potential Black juror was excused because he insisted he could not be fair. All three officers also face State charges for aiding and abetting Floyd’s murder. Their trial on that case is set to begin June 13.

TRIAL

WEEK 1

DAY 1 (1/24/22)

Opening Arguments

Prosecution

“In your custody is in your care.” That’s not just a moral responsibility, it’s required by law. But instead of intervening and providing medical aid - officers will testify that both are mandatory - the accused “watched” as Mr. Floyd, his breath “crushed” by Chauvin, “suffered a slow, agonizing death.” It’s not that the officers didn’t realize it; Floyd begged for help and said “I can’t breathe” twenty-five times.

Referring to Tou Thao, the prosecutor mentioned he was right next to Chauvin but did nothing. And when a bystander complained that Floyd was passing out, Thao said “that’s what happens when you’re lying on the ground.”

Referring to J. Alexander Kueng, the prosecutor said he ignored Floyd’s “a knee on my neck, I’m through.” Kueng did nothing as Chauvin kept pressing down on Mr. Floyd, and even after Kueng couldn’t detect a pulse. Kueng was also accused of joining with Chauvin in rejecting officer Lane’s suggestion to roll Floyd onto his side.

Referring to Thomas Lane, the prosecutor said he did nothing when the other officers rejected his suggestion to place Floyd on his side.

Defense

Lawyer for Tou Thao (Robert Paule)

His lawyer brought up Floyd’s failure to comply with Lane and obvious drug intoxication. He also mentioned that Lane and Kueng were rookies, but Thao was an experienced officer. And when Thao and Chauvin arrived, the rookies were struggling with Mr. Floyd. And the struggle continued. Thao then had to deal with “vociferous” bystanders. He pointed out that his client’s behavior has to be proven “willful” (meaning purposefully deprived Floyd of his rights; not through accident or misunderstanding.) He also cautioned that “use of force is often disturbing to watch and difficult to comprehend.” And while he agreed that Floyd’s death was tragic, he reminded jurors that didn’t mean that his client committed a crime.

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

Lawyer for J. Alexander Kueng (Tom Plunkett)

Kueng’s lawyer emphasized that his client was a rookie with limited and inadequate training. Kueng had to assume that Chauvin, his training officer, knew best. When Kueng and another rookie, Thomas Lane were paired up as partners, each had only served five full post-training shifts. Kueng’s lawyer emphasized the severity of the struggle with Mr. Floyd. And he pointed out that when Chauvin, the senior man arrived, he “becomes the shot-caller,” as senior officers “know things that rookies don’t.” Again, Kueng’s lawyer emphasized the Government’s obligation to prove that Kueng acted “wilfully.”

Lawyer for Thomas Lane (Earl Gray)

Lane is charged with one count: being “wilfully” and “deliberately indifferent” to Floyd’s medical condition. But the lawyer insists that his client did everything “he could possibly do” to help Floyd. Lane, who was paired with another rookie, was told that Chauvin was an excellent training officer and to “follow what he does.” Lane was faced with getting Mr. Floyd, a large, powerful man who was under the influence of drugs and behaving erratically, out of his car. Lane wound up in a position from which he couldn’t see Chauvin’s knee on Mr. Floyd’s neck, and the only pressure he exerted was on Mr. Floyd’s feet. Lane’s lawyer mentioned that “excited delirium,” a condition in which persons exhibit “superhuman strength,” was taught at the police academy. But when Lane said that might apply to Mr. Floyd, and suggested rolling the man on his side, Chauvin refused. Lane then asked to accompany Mr. Floyd in the ambulance and performed chest compressions to revive him. His actions, emphasized his lawyer, were “not deliberately indifferent at all.” Lane’s lawyer said his client will testify.

Prosecution case

Kimberly Meline, FBI. Day’s only witness is FBI employee Meline, who synchronized videos that were taken by officers and bystanders during the incident. First video begins with officer Lane inside his SUV. He approaches Floyd sitting in the Mercedes, points his gun and tells Floyd to exit. For our video compilation that tracks the entire episode, click here.

Video clips include Floyd struggling against being in a police car, saying “I’m not a bad guy” and “I can’t breathe.” Lane tries to reassure him, but to no avail. On ground, Floyd begs for his “mama”, repeats that he can’t breathe. As his movements slow crowd members start yelling at police. “You think that’s cool”, ”He’s not responsive”, “You’re a bum, bro”.

DAY 2 (1/25/22)

A defense lawyer complains that the prosecution is trying to overwhelm the jury with a “tidal wave” of cumulative video. His objection does not seem to have an effect.

Prosecution case continues

Kimberly Meline, FBI. Prosecutors show more of the videos she synchronized. These track the encounter from beginning to end. Floyd is depicted sitting handcuffed, against a wall. Kueng angrily tells him to behave, Floyd says “I don’t want no problems.” Lane, Kueng and Floyd cross the street. Floyd resists getting in the police car. Chauvin and Thao arrive. Chauvin exercises “pain compliance” by pulling up on Floyd’s cuffs. Floyd is pulled out of the car and placed on the ground.

Floyd’s movements slow and he grows still. Bystanders express concern. One yells “he's not responsive now, bro. Is he breathing right now? Check his pulse.” Kueng does so. A man named “Donald Williams” repeatedly yells at Thao to “get off his f... neck.” He protests that Floyd is “not f... moving,” calls Chauvin a “bum,” demands that officers check Floyd’s pulse. An off-duty firefighter walks over, does likewise.

Floyd, who is unconscious, is loaded into the ambulance. None of the officers seems distraught. Kueng later tells a bystander that Floyd was “uncooperative.”

Christopher Martin, Cup Foods clerk. Floyd gave Martin a phony $20 bill for cigarettes. Martin said that he realized that immediately, and that Floyd seemed “high.” Martin said he intended to have the $20 taken from his paycheck. But his manager told him to have Floyd come back and make it right. Martin and another employee went to the car and tried, but without success.

Martin later saw Floyd on the ground. He seemed “dead...not moving.” He took a video of officer Thao pushing a bystander onto the sidewalk. Officer Thao’s bodycam shows him pushing the man as well.

On cross-examination, Martin confirms that he later told the FBI that Floyd “was on something.” He also conceded that his co-worker didn’t seem to follow Thao’s instructions before he got pushed.

Charles McMillian, passer-by. McMillian observed the officers’ initial interaction with Floyd, then the struggle in the car. McMillian walked up and told Floyd to get in the car, that he was in handcuffs and couldn’t win. But Floyd said he was claustrophobic. After the officers put Floyd on the ground McMillian got worried. A video shows him imploring the officers to let Floyd breathe. McMillian testified that “I knew something bad was going to happen to Mr. Floyd... That he was going to die.”

On cross-examination, McMillian confirmed that he heard Lane offer to roll down the police car’s windows. On re-direct by the prosecutor, McMillian said that he didn’t observe Floyd direct violence or threats at any officer. “I didn't see him resisting at all; I saw him begging.” On re-cross, McMillian was asked if he saw Floyd resisting getting in the squad car, then fighting with his legs and body (this behavior is clearly depicted on officer bodycam video.) No answer is apparent.

Jena Scurry, 9-1-1 dispatcher. She testified that the initial call for medical help was about “a mouth injury.” Nothing was said about someone being unconscious or not breathing. In such cases the matter would become a “rescue.” After a delay, the call was apparently upgraded.

DAY 3 (1/26/22)

Prosecution case continues

Derek Smith, paramedic. First on scene, testified Floyd was dead when encountered. Video shows Lane in the ambulance, checking Floyd’s pulse.

On cross-examination, says that Floyd was treated for cardiac arrest. Agrees that Lane was helpful. Smith says he was trained that “excited delirium” (E.D.) can lend “superhuman strength” and cause cardiac arrest. Says that ketamine is used to sedate persons in its throes. Smith’s notes indicate that Floyd was sweating excessively. Thao’s defense lawyer notes that’s consistent with E.D.

Jeremy Norton, firefighter/EMT. On arrival, overheard someone yell “you all killed that man.” Scene felt unsafe but officer Thao didn’t seem worried. An off-duty firefighter approached, said “I think they killed him.” On cross-examination, says he was trained on E.D. Norton is skeptical about E.D., calling it a “catch all” term for agitated and struggling persons. He questions whether “it’s solid science” and says that the AMA opposes the diagnosis.

Genevieve Hansen, off-duty firefighter. Says she was out for a walk, heard a woman yell “they were killing him.” On approach noticed “the amount of people” on top of Mr. Floyd. He was unconscious and had seemingly emptied his bladder, “a sign of death or near death.” Floyd clearly needed help but no medics were present. She told officer Thao to check Floyd’s pulse but he didn’t. He ordered her back on the sidewalk and said she should “know better” than to get involved. He was keeping Floyd from getting help. “It didn’t seem like a normal scene.”

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

On cross-examination Hansen agrees that her “bladder emptying” observation was incorrect. She denies that her “you can find me in the streets” comment to Lane was a threat.

DAY 4 (1/27/22)

Prosecution case continues

Inspector Katie Blackwell, former MPD training head. She testified that a police academy graduate is qualified to work on their own. Regulations require officers immediately report any breach of rules they observe. Officers must only use the “lowest level of force” possible, what an “objective” officer would find “reasonable.” And once they “gain compliance, then the force stops.” Officers are obligated to protect those they encounter and must intervene if inappropriate force is being used. Intervention was always a practice and became official policy in 2016.

Officer Blackwell discussed conscious and unconscious neck restraints. The latter can be used when escalating, fighting, or trying to save a life. They are “one more thing you can try before shooting somebody.” It takes about 15 seconds for a neck restraint to cause compliance.

She also discussed proning suspects out for handcuffing. If they are placed in the “maximal” position (face down, on their stomachs) it is “critical” and required by policy that they be placed on their side as soon as possible.

MPD policy requires treating persons compassionately. If there is a medical emergency officers must render first-aid and summon EMS.

Dr. Bradford Langenfeld, physician who treated George Floyd. Said that Floyd arrived in cardiac arrest wearing a chest device that provides compressions. Paramedics never found a pulse. He had reported that the most likely causes of Floyd’s cardiac arrest were “mechanical asphyxia” and excited delirium or “severe agitated state.” Fentanyl is a depressant that would slow breathing but not cause agitation. Dr. Langenfeld said that he hadn’t known that someone was on top of Floyd.

On cross-examination, Dr. Langenfeld said excited delirium is controversial because it’s over-diagnosed. It’s most often used when minorities are restrained by police. The AMA has also condemned it. Asked whether emergency physicians feel differently, he replied that excited delirium is a pre-hospital rather than in-hospital diagnosis. [Note: click here for the EMRA post about excited delirium, here for the ACEM white paper, and here for our related post.] Persdons in E.D. can be delirious, irrational, combative, sweaty and show symptoms of mental illness or drug overdose. Dr. Langenfled agreed that cardiac arrest could be caused by excessive sweating and use of drugs, and by using meth and fentanyl, then getting involved in a struggle.

On redirect, Dr. Langenfeld said that the struggle depicted in the videos was insufficient to cause cardiac arrest.

DAY 5 (1/28/22)

Prosecution case continues

Inspector Katie Blackwell, former MPD training head. She returned to the stand. Began with Thao. His 2018 refresher training instructed officers to use “the lowest level of force.” Neck restraints can’t be used for “passive” resisters. “Conscious” neck restraints can be used on active resisters, and an “unconscious” neck restraint for “active aggression.” When someone has been proned out, getting them up ASAP is necessary to prevent positional asphyxia. That’s emphasized in a 2012 medical examiner video which discusses the case of a man who suffocated in 2010.

Shifts to rookies Kueng and Lane. Reads orders that state officers are accountable for what they do and don’t do, and for the actions of other officers. According to policy, first officers on scene are in charge. So Lane and Kueng were in charge. What they and Thao did was “inconsistent” with use of force policy. Shown a photo of Chauvin’s knee on Floyd’s neck, she said this was improper, not a “trained technique,” and that Chauvin should have been in a side recovery position. Lawyers for Kueng and Lane object, saying their clients hadn’t been in a position to see what the photo depicts.

Floyd’s kicking constituted aggression, thus “active” resistance. Officers could have used a Taser. Chauvin’s knee on neck and his pulling up on Floyd’s handcuffed hand, “pain compliance,” were wrong because Floyd wasn’t resisting.

After Floyd went unconscious Chauvin didn’t move, risking positional asphyxia. Lane’s suggestion to roll Floyd over was correct. Faults officers for failure to communicate and failure to intervene to stop the use of excessive force. When Floyd went unconscious they were obligated to render aid. Same, when they found out he had no pulse. They weren’t held back from acting by the crowd, which didn’t pose “an immediate threat” and stayed on the sidewalk. Prosecutor plays video of crowd. Blackwell says all Thao did was watch them.

On cross-examination by Kueng’s lawyer, Blackwell disagreed that agency “culture” is set by senior leaders and through training. She concedes officers are only tested on “some parts” of the 537 pg. manual. She confirms DOJ is investigating alleged deficiencies at MPD, including officer training. Kueng’s lawyer asks about paramilitary aspects of the academy. Blackwell agrees that recruits must show “instant and unquestioned obedience” to academy staff. She says she tried to change things but couldn’t. She also denies that an FTO’s (field training officer) opinion could be the “sole” reason for termination. (Chauvin was Kueng’s FTO during his last two phases of training.)

Kueng’s lawyer points out that officers must “attempt” to intervene when others use excessive force, but that Blackwell left that word out. Blackwell says there is no specific intervention scenario in training. Kueng’s lawyer points out that “intervention” is not mentioned in the lesson plan or in the FTO handbook.

Blackwell agrees that Lane was by policy in charge of the encounter. But Kueng’s lawyer points out that Chauvin, a 19-year veteran, ignored three requests to roll Floyd onto his side.

WRAP - WEEK 1 (prosecution case)

According to his attending physician, Mr. Floyd died from cardiac arrest brought on by “mechanical asphyxia” and “excited delirium.” Focusing on the first cause, asphyxia, the prosecution emphasized Mr. Floyd’s needlessly prolonged, forceful restraint, which continued even after an officer failed to detect a pulse and passers-by complained that the arrestee was unconscious. Because Chauvin controlled Mr. Floyd’s positioning and was the one who persistently applied improper force to Mr. Floyd’s upper body and neck, emphasis was placed on his colleagues’ duty to intervene. It was also mentioned that MPD placed those first on scene (Kueng and Lane) in charge.

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

In cross-examination, defense lawyers sought to highlight the second cause of death, “excited delirium,” whose principal component - Mr. Floyd’s drug intoxication - preceded his arrest. They also challenged the notion that “intervention” was an actual practice and pointed out that it did not appear as a component of the agency’s formal training program. Both of the officers first on scene - Lane and Kueng - were rookies, and the defense disputed that given the agency’s militarized atmosphere, they could tell Chauvin, a 19-year veteran, what to do. Indeed, Chauvin ignored officer Lane’s comment about “excited delirium” and three requests by Lane to roll Mr. Floyd onto his side.

WEEK 2

DAY 6 (1/31/22)

Prosecution case continues

Inspector Katie Blackwell. Her cross-examination resumes. Under questioning by Thao’s lawyer, she confirmed that MPD provides extensive instruction on excited delirium (ExDS). Training materials describe its symptoms as “psychomotor agitation, anxiety, hallucinations, elevated body temperature, super human strength.” Officer training videos show ExDS sufferers acting erratically and aggressively and officers responding forcefully, often pinning them down with their knees. Blackwell confirmed that none of the training videos (and only one of the slide shows) depicts the use of a side recovery position. (For an MPD PowerPoint about ExDS click here, and for a training video click here.)

Blackwell confirmed that officers are trained to physically contain ExDS sufferers until EMS arrives and sedates them with Ketamine. This practice, she confirms, is in direct conflict with a city civil rights report that disparages ketamine’s use for this purpose as “wrong and uninformed.”

Lane’s attorney points out that chokeholds and neck restraints were permitted when his client was in the academy. Also, that the duty to intervene is to “stop or attempt to stop.” Blackwell agrees that Lane de-escalated by getting Mr. Floyd out of his car and offering to roll down the police vehicle’s windows. She also agreed that Lane had no duty to intervene while Mr. Floyd was actively resisting. And she also thought that Lane, who suggested that Mr. Floyd be rolled over and asked about his pulse, went beyond what was required by helping paramedics and joining them in the ambulance.

On redirect by the prosecutor, Blackwell confirmed that officers are supposed to stop using force and place persons in a side recovery position once they become compliant. When pressed on why MPD trains officers about ExDS, which is “controversial,” she replied that persons who display its symptoms “can be very dangerous.” She agreed that officer Lane did “nothing” even Floyd had no pulse and Chauvin’s knee was pressing on his neck. Also, that none of the officers rendered aid. She also mentioned that an FTO could not by themselves fail a recruit.

On re-cross, Blackwell confirmed that placing a person on their side to prevent asphyxia is mentioned in only one place on a training Power Point. She also agreed that a single symptom is enough to diagnose ExDS. Under challenge by Lane’s lawyer, who referred to her previous positive comments about Lane’s behavior, she insists that Lane did not render aid or stop anything from happening.

County medical examiner Andrew Baker. Dr. Baker, the pathologist at Mr. Floyd’s autopsy, testified that “subdual restraint” (knee-on-neck) and neck compression contributed to Mr. Floyd’s death through asphyxia. He confirmed that Mr. Floyd had an enlarged heart, hypertension and narrowing of the coronary arteries. But he didn’t consider them sufficiently severe to contribute to Mr. Floyd’s death. He also does not think that the fentanyl and meth in his system were an “immediate” cause of death.

DAY 7 (2/1/22)

Prosecution case continues

County medical examiner Andrew Baker. Under cross-examination by Thao’s lawyer, Dr. Baker said that excited delirium is a syndrome, thus difficult to define. Its sufferers have usually ingested drugs. They sweat profusely, remove their clothes, and exhibit “super-human strength.” Whether the syndrome is over- or under-used he couldn’t say.

Asked about prone restraint, Dr. Baker said that his “understanding from the literature” is that it’s “not inherently dangerous.” His autopsy didn’t reveal any damage to muscle or bone in Mr. Floyd’s neck. Mr. Floyd’s lack of blood spots in his eyes, while not definitive, is also inconsistent with the theory that critical blood vessels in his neck were compressed. Dr. Baker agreed it was possible that Floyd was experiencing an unrelated “cardiac event.” Given his heart disease and hypertension, stressing the heart could make “deleterious” things happen.

Kueng’s lawyer takes over cross-examination. Reacting to an image of Kueng’s knees on Mr. Floyd, Dr. Baker says “I’m not even sure it’s that high on Floyd’s body.” Lane’s attorney then asks about his client’s position on Mr. Floyd’s legs. Dr. Baker said it was “completely unrelated to Mr. Floyd’s ability to breathe.”

Christopher Douglas, juvenile detention center training officer. He trained Lane on de--escalation and physical restraint while the accused worked as a juvenile corrections officer. Under direct examination Mr. Douglas said the objective is “to keep someone vertical and on their feet.” He said that Lane took a class on positional asphyxia, and that one of the warning signs is a complaint by the person being detained that they can’t breathe.

On cross-examination by Lane’s lawyer, Mr. Douglas said he didn’t check if Lane had been accused of using unreasonable force during his year-and-a-half of service.

WRAP - WEEK 2 (prosecution case). Note: This week was cut short by the news that defendant Lane tested positive for COVID. Excited delirium received extensive attention, and two witnesses (an MPD Inspector and the autopsy pathologist) confirmed that it may apply here. Mr. Floyd’s medical history received considerable attention. While the pathologist felt that preexisting heart problems may have played a role, he mostly attributed Mr. Floyd’s death to asphyxia brought on by Chauvin’s use of his knee. Training videos played by the defense, though, showed officers using their knees to control persons supposedly suffering from ExDS. MPD’s Inspector conceded that none depicted officers rolling suspects onto their sides. But she criticized the accused for not intervening even though Mr. Floyd had stopped resisting and was clearly in serious medical distress.

WEEK 3

DAY 8 (2/7/22)

Trial was postponed Wednesday, February 2 because one of the accused - presumably Lane, the only defendant not in court - tested positive for COVID-19.

Prosecution case continues

Dr. David M. Systrom, pulmonologist. Dr. Systrom is an expert retained by the prosecution. He testified that Mr. Floyd did not die from his pre-existing heart conditions, a heart attack, or an overdose of drugs. As confirmed by his repeated complaints of “I can’t breathe,” gradual loss of speech and loss of consciousness, and ending CO2 volume, “Mr. Floyd died of asphyxia.” There were two main causes: forcible prone restraint against the asphalt, which impeded his breathing, and compression of the airway. Mr. Floyd’s “respiratory failure” was “eminently reversible” until he passed out, and even then he could have survived had CPR been immediately begun.

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

Kueng’s physical pressure on Mr. Floyd “added to the restriction” on breathing. Lane didn’t directly affect Mr. Floyd’s ability to take in oxygen, but pinning the victim’s ankles helped keep him from “self-rescuing.”

On cross-examination by Thao’s lawyer, Dr. Systrom said there was no evidence that Mr. Floyd had sought medical care for his cardiac conditions. In reply to Kueng’s lawyer, who described the initial struggle between the officers and Mr. Floyd “ferocious,” he agreed “there was a struggle.”

Nicole Mackenzie, MPD medical support coordinator. Ms Mackenzie testified that officers are instructed about airway, breathing and circulation (“the ABC’s”) and are told to roll persons onto their sides (“side recovery position”) should they become unresponsive.

DAY 9 (2/8/22)

Prosecution case continues

Nicole Mackenzie, MPD medical support coordinator returns to the stand. Defendants Lane and Kueng were trained to administer CPR and identify persons in medical distress, including cardiac arrest. Thao received CPR in-service training in 2019. Ms. Mackenzie confirmed that excited delirium is a training topic. But in practice it’s actually “quite rare,” and that during her five years in the field “I may have seen this maybe once.” (Under cross, she later agrees that the symptoms of ExDS vary.) As to positional asphyxia, she testified that officers are not trained that being able to talk means someone can properly breathe. She also said that officers are instructed to place those in the throes of excited delirium on their sides.

On cross-examination, Thao’s lawyer displayed images and videos used during MPD training. Officers are shown placing their knees on suspect’s necks and, in one case, across an upper shoulder blade. Ms. Mackenzie confirms that’s similar to what Chauvin did. She agrees that officers are using their knees to control suspects, and that instructors didn’t step in and say that’s wrong. But she insists that the circumstances shown are “extreme” and that using a knee wasn’t part of her training. She’s then asked about the crowd’s potential impact on officer decision-making. Ms. Mackenzie concedes it could have affected the officers’ assessment of Mr. Floyd. She confirms personally observing bystanders “attacking” medical responders. She also said that the accused had no way to get EMS to the scene more quickly.

Lane’s lawyer began cross-examination by noting that medics didn’t immediately tear off Mr. Floyd’s clothing and apply CPR, “yet you're willing to judge these officers, these rookie officers...” That drew an objection, which was sustained.

DAY 10 (2/9/22)

Prosecution case continues

Dr. Vik Bebarta, university medical instructor. Retained by the prosecution as an expert in emergency medicine, pharmacology and toxicology. He disagreed that heart disease and high blood pressure were contributing factors as indicated on the death certificate. Mr. Floyd did not exhibit signs of an impending heart attack, nor, as chemistry confirms, did he have one. Drugs in his system were in low concentrations and two - meth and fentanyl - counteract each other. So death wasn’t due to an overdose. It was caused by his suffocation, which led to “a lack of oxygen to his brain.” He could have survived if given CPR by “the officers that were standing on him.”

On cross-examination, Thou’s lawyer and Dr. Bebarta sparred about the underlying condition that best accounts for Mr. Floyd’s general behavior. Reading from a paper about ExDS and AgDS (“agitated delirium”) Dr. Bebarta testified that these aren’t diagnoses but syndromes - collections of symptoms. He’s often observed their presence. Mr. Floyd, he said, was not suffering from ExDS but from AgDS, which is connected with psychosis and drug use.

Lane’s lawyer mentioned that officers Lane and Kueng were concerned about whether Mr. Floyd was breathing and checked his pulse. On redirect, Dr. Bebarta suggested that what was happening to Mr. Floyd was obvious.

McKenzie Anderson, forensic biologist, Minn. Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. Her team gathered evidence from two vehicles Floyd had occupied: the Mercedes he was found in, and the police car in which he was first placed. Pills and fragments in the Mercedes tested positive as meth.

DAY 11 (2/10/22)

Prosecution case continues

Under cross-examination, State forensic biologist McKenzie Anderson said that she was looking for blood evidence, counterfeit currency and a cell phone. She confirms to Lane’s lawyer that DNA on a pill found in the police car matched Mr. Floyd.

Lieutenant Richard Zimmerman, MPD chief of homicide. Arrived on scene about 1 1/2 hours after Floyd’s death. Testified that it’s everyone’s responsibility, from the chief on down, that “if you see another officer using too much force or doing something illegal, you need to intervene and stop it.”

According to Lt. Zimmerman, the officers who handcuffed Mr. Floyd (Lane and Kueng) were in charge of the scene. He spoke with them first. Their accounts about the amount and type of force and the aid rendered to Mr. Floyd wound up being “totally different” from their body camera footage. That revealed a grossly excessive use of force and Chauvin’s appalling “knee on the neck” routine. Lt. Zimmerman strongly criticized the defendants’ failure to intervene and roll Mr. Floyd onto his side, and their failure to try to revive him when he became unresponsive.

On cross-examination, Kueng’s lawyer pointed out that officers are supposed to “attempt” to stop the improper use of force. Zimmerman conceded that Chauvin’s reputation as a “prick” and a “jerk” (his past words) made him a poor choice as a training officer. Thao’s lawyer challenged Zimmerman’s view that the crowd was not unruly. Zimmerman said that was his opinion, and confirmed that he had been threatened by crowds in the past. He also agreed that Chauvin, as senior officer, was “essentially” in charge.

Zimmerman agreed with Lane’s lawyer that reholstering a gun, as Lane did, is hard to do. But the lieutenant expressed skepticism that even a “40-day rookie,” as the lawyer described his client, should have believed Chauvin when he said, after Lane mentioned excited delirium, that an ambulance was coming.

On redirect about Lane, Zimmerman said that bystanders were appalled that “Mr. Floyd was slowly being killed” and simply wanted to help. As for intervening, it “means just that, not suggesting...Mr. Floyd was handcuffed by him and his partner and they should have taken care. It’s that simple.”

DAY 12 (2/11/22)

Prosecution case continues

Kelly McCarthy, Chief of Police, Mendota Heights, Minn. Ms. McCarthy chairs the state’s peace officer standards and training board. She confirmed that the defendants were duly certified police officers. She testified that positional asphyxia “is so close to the position that we put people in for handcuffing.” Chief McCarthy emphasized that persons in custody “are essentially your baby” and must receive appropriate care. She also affirmed officers’ obligation to insure that their colleagues are acting legally and ethically.

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

Alyssa Funari, bystander. Ms. Funari, then a 17-year old high school student, observed that Mr. Floyd was being forcibly held down and had Chauvin’s knee on his neck. He was in obvious “distress” and complained “I can't breathe, you're on my neck, tell my mom I love her. It hurts.” Videos are played in court. She is heard yelling “he's not moving in over a minute” and reproaching Thao with “you should be able to multitask” and “you stand behind your coworkers, right? Those are your partners, right?” Ms. Funari said that Mr. Floyd soon grew less vocal. “He wasn’t telling us that he was in pain anymore, he was just accepting it.”

On cross-examination by Thao’s lawyer, Ms. Funari says she didn’t hear anyone tell Floyd to “stop fighting.”

Matthew Vogel, FBI special agent. Agent Vogel trains police about “color of law” civil rights violations. He used twelve videos to build a timeline of the episode. It begins at 8:08 pm as Lane and Kueng arrive. Six minutes later they’re shown walking Mr. Floyd to the police car.

Mr. Floyd’s ground restraint began at 8:19 pm. Twenty-five seconds later, as Kueng’s forearm pressed into his neck, Mr. Floyd uttered his first “I can’t breathe.” About a minute later Lane asked about raising Mr. Floyd’s legs. Chauvin and Kueng both said no. Thao asked Mr. Floyd “what are you on?” and Mr. Floyd responded “I can’t breathe, a knee on my neck.”

Thao summoned an ambulance “code 3” (emergency, lights and siren) at 8:21:23. About a minute later a bystander who had urged Mr. Floyd to get in the police car told the officers to get off Mr. Floyd’s neck. About a minute after that Lane asked “should we roll him on his side?” Chauvin and Kueng again turned him down. Kueng: “Just leave ‘em.” Chauvin: “staying put the way you got ‘em.”

Moments later, at 8:23:57, Floyd uttered his last “please, I can’t breathe” Thao said “OK, he’s talking. It’s hard to talk if you’re not breathing.” One minute later Lane said “Yeah, I think he’s passing out.” Mr. Floyd is unconscious at 8:25. Kueng and Lane both reported he was breathing. Thirty seconds later Lane again suggested rolling Mr. Floyd onto his side. He got no response. Off-duty firefighter Genevieve Hansen had been yelling to check Mr. Floyd’s pulse, and Lane seconded it. Kueng quickly checked twice and reported that he couldn’t detect one.

Mr. Floyd’s restraint ended at 8:27. EMT’s arrived at 8:27:26, about six minutes after Thao’s call. Lane told them that Mr. Floyd is “not responsive.” CPR in the ambulance began at 8:30:45.

WRAP - WEEK 3 (prosecution case)

Prosecution medical experts testified that Mr. Floyd was asphyxiated by physical pressure. They rejected the notion that he had a heart attack and insisted that neither drug use nor pre-existing medical conditions played a significant role in his death. Most of the blame was placed on Chauvin’s use of his knee. Kueng’s application of pressure was also mentioned. Most damningly, the experts agreed that Mr. Floyd might have survived had officers promptly initiated CPR. Records showed that each defendant had been trained on the technique.

Of course, struggling with suspects carries risks. Indeed, a policing expert said that asphyxia “is so close to the position that we put people in for handcuffing.” There’s been abundant testimony that officers are trained to roll persons onto their sides as soon as possible. Defendant Lane’s repeated suggestions to do exactly that featured prominently in the videos.

But did his “suggestions” amount to “intervention”? Policing experts have emphasized that officers are both trained and required by regulations to intervene when an officer misbehaves. An MPD commander testified that intervening is much more than “just suggesting.” Yet Lane and Kueng were rookies, so his testimony that as the initial officers on scene they were actually in charge falls flat. Indeed, the witness conceded on cross-examination that Chauvin, by far the most senior officer, was “essentially” in command. On redirect, though, he threw in that Lane and Kueng “should have taken care. It’s that simple.”

But is it really?

WEEK 4

DAY 13 (2/14/22)

Prosecution case continues

Timothy Longo Sr., Chief of Police, University of Virginia. Acting as an (unpaid) prosecution expert, Chief Longo called Mr. Floyd’s forceful and prolonged restraint “inconsistent with generally accepted police practices.” Mr. Floyd, he noted, had only resisted to avoid being placed in the police car, and the use of force that followed was grossly disproportionate to any possible threat he might have posed. Chief Longo testified that there was no legitimate reason to put Mr. Floyd on the ground. He also said that officers are well aware that doing so, and particularly when someone is handcuffed, can imperil their breathing, so they know to promptly bring them to their feet.

Chief Longo emphasized that officers have an “absolute” duty to care for persons in their custody and to “protect people who can't protect themselves.” Accordingly, he sharply criticized the defendants’ failure to “affirmative steps, to do something” about Chauvin’s misuse of force. During a reportedly loud and bitter exchange with Lane’s lawyer, Chief Longo called his client’s requests to roll Mr. Floyd onto his side insufficient. Brushing aside the objection that repositioning Mr. Floyd would have required officers to use force against their superior, Chief Longo pointed out that the defendants never even asked Chauvin to remove his knee.

Darnella Frazier, bystander. Ms. Frazier, then sixteen years old, filmed the officers’ encounter with Mr. Floyd. She watched as he gradually lost consciousness. “Over time, he kind of just became weaker and eventually just stopped making sounds overall.” Ms. Frazier said that Mr. Floyd wasn’t resisting the officers but only trying “to breathe and get more oxygen.” Then-officer Thao was “patrolling and protecting,” but the only person who needed protection was lying on the ground.

Prosecution rests.

DAY 14 (2/15/22)

Defense case begins

Defendant Tou Thao took the stand. His lawyer posted a 2009 training photo depicting Thao and a classmate holding down a prone actor-suspect. Thao testified that they were using their knees as trained, and that instructors never said that doing that was improper. Thao confirmed that his training was military-style, and his lawyer posted images of trainees running and marching in formation. After the academy Thao was laid off and worked as a hospital security guard. He helped restrain patients and noticed that “excited delirium” was sometimes noted on their medical records.

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

Thao’s lawyer switched to the episode with Mr. Floyd. Thao testified that he and Chauvin heard that Lane and Kueng were having problems so they hurried to help. Mr. Floyd seemed to be on drugs and in a state of excited delirium. In eight years as a cop he had “not seen this much of a struggle” to get someone into a police car. Thao said that he subsequently assumed the role of “human traffic cone” and also sought to control the crowd that had formed.

During cross-examination the prosecutor mentioned that using a knee to control “is entirely different than using a knee on their neck when they’re already handcuffed.” Thao confirmed that one can only use the force that’s reasonable under the circumstances. He agreed that since he and Chauvin were backup officers, the decision to arrest was Lane and Kueng’s to make. He also agreed that one can’t ignore “I can’t breathe” just because someone else said so untruthfully.

Thao disagreed that male officers, due to their unique vulnerability, can safely straddle a suspect to keep them from “reanimating”. He conceded that once suspects are handcuffed and under control they should be rolled onto their side. But when the prosecutor characterized Mr. Floyd’s “please” and “Mister officer” as respectful requests, and noted that he didn’t flee, Thao disagreed. “He escaped out of the squad car.”

Thao said that he suspected Mr. Floyd had “a drug issue.” He agreed that he could “generally” observe his colleagues’ interaction with Mr. Floyd. He saw Chauvin’s knee on Mr. Floyd’s neck, heard Mr. Floyd say “I can’t breathe,” and noticed that Mr. Floyd had gone silent and was possibly unconscious. Videos from the third minute of the restraint depict Thao looking down as he stood near his partners and Chauvin. He conceded the “possibility” that by then Mr. Floyd had altogether stopped resisting.

DAY 15 (2/16/22)

Defense case continues

Defendant Tou Thao remained under cross-examination. Challenged about images that depict Mr. Floyd being held down after he stops resisting, Thao said they showed that “the restraint was successfully working.” And if Mr. Floyd suffered from ExDS, as he seemed to, he had to be kept on the ground until EMS arrived as he could again pose a threat. As restraint continued bystanders asked him to check on Mr. Floyd. But Thao said that was his colleagues’ job, and that his was crowd control. (When off-duty firefighter Genevieve Hansen asked him to check Floyd’s pulse, Thao responded “I’m busy trying to deal with you guys.”) During the fifth minute of restraint, when Floyd spoke what would be his last words, Thao told the crowd “it’s hard to talk if you’re not breathing.” Thao agrees he never told Chauvin to get off Mr. Floyd. He trusted “the 19-year veteran” to do the right thing,

On redirect, Thao asserted that Mr. Floyd was suffering from ExDS and “to save his life we need to hold him down for medical personnel.”

Two character witnesses briefly took the stand. Thao’s wife, Sheng Yang, testified that her husband was a truthful person.

Thao’s defense rests. Kueng’s defense begins.

Joni Kueng, the mother of defendant J. Alexander Kueng, called her son compassionate and law-abiding. They were not cross-examined.

Defendant J. Alexander Kueng takes the stand. He began as a Community Service Officer. His training then included a brief mention of the duty to intervene. That responsibility was also briefly addressed at the academy with an example that showed an officer violently punching, stomping and kicking a suspect. What the academy did emphasize was that “the chain of command is not to be breached.” A field training officer (FTO) was a “mentor, role model, educator, terminator.” Chauvin, his FTO through half his training, was “by the book,” highly thought of and deferred to by others.

Kueng responded to the call with Lane. He described Mr. Floyd as behaving erratically, as though he was on drugs. And in the car he got extremely combative. Kueng said he’s dealt with strong men but “never struggled as with Mr. Floyd.” As for who was in charge, policy says it’s the senior officer in the first car on scene. But in actual practice it’s always the senior officer, period. And once Chauvin arrived, it was indisputably him.

Kueng testified that he held Floyd down as he did because “the hips are very important for generating power and ultimately I wanted to avoid the spine.” He saw Chauvin’s knee on Mr. Floyd’s upper back and neck area, although not precisely where. He testified that he learned during training that if someone can speak they can breathe. As to his “leave him, yep” remark when Lane asked about raising Floyd’s legs, he was just passing on what Chauvin said in case his partner, because of his position, couldn’t hear.

Kueng said that he told Chauvin he couldn’t find a pulse. But until Lane returned from the ambulance he hadn’t considered Mr. Floyd as being in dire straits. He thought that maybe the handcuffs were causing a weak pulse, and that in in a “more controlled environment” he would “spring back to life.”

DAY 16 (2/17/22)

Defense case continues

Cross-examination of J. Alexander Kueng. Kueng agreed that if there’s no pulse and someone’s not breathing “time is of the essence.” Disagreeing with the prosecutor, he insisted that Floyd’s behavior was consistent with excited delirium. In case of ExDS he was trained to keep the suspect restrained and call for EMT’s. When the prosecutor says “in side recovery position?” Kueng replied “when it’s safe to do so.” He said he did not focus on Chauvin’s knee position and was not himself pressing into Mr. Floyd - just trying to keep his balance. He confirmed checking Mr. Floyd’s pulse twice during the latter stages of his restraint. Kueng acknowledged a “brief moment of levity” after Mr. Floyd was removed.

Kueng agreed that MPD policy placed Lane in charge because he was senior to Kueng and they were first on scene. Kueng confirmed that he responded “no” when Lane asked about rolling Mr. Floyd onto his side. He disagreed that Chauvin “didn’t have control over your employment.” He said that he was still on probation and said that Chauvin could “unilaterally” get him fired.

As on the previous day, Kueng said he didn’t think Mr. Floyd was in dire straits. He didn’t take a confirmatory carotid pulse or start CPR because ExDS still made Mr. Floyd potentially dangerous and it would have required moving him. Challenged about not telling Lt. Zimmerman that Chauvin had his knee on Mr. Floyd’s neck, Kueng said that was for Chauvin to mention. He agreed that the duty to intervene trumps worries about repercussions from a superior.

Stephen Ijames, Asst. Chief (ret.) Springfield (MO) Police Department. Chief Ijames testified as an expert witness for the defense. He said that MPD’s “duty to intervene” policy is “inadequate” and relies on an “overly simplistic example” (it depicts an officer beating a handcuffed man) that “does nothing to train an officer.” He added that for new cops a police department’s “culture” is set by a training officer. Chief Ijames agreed that once Mr. Floyd was on the ground and under control excessive force was used. But he added that officers in Kueng’s position would defer to their seniors.

Under cross-examination, Chief Ijames confirmed that Kueng was “authorized to perform the same duties” as Chauvin, but added that new cops don’t perform like experienced officers. He confirmed that Kueng “lacked the training and experience to recognize Mr. Chauvin’s excessive use of force.” Chief Ijames interpreted Chauvin’s response when asked to roll Mr. Floyd over as “a denial” of the request. He agreed that persons suffering from ExDS should be rolled over, but only “when safe and practical.” He also agreed that the bystanders did not seem to be threatening the officers.

Kueng’s defense rests. Lane’s defense begins.

Gary Robert Nelson, retired MPD Lieutenant. Mr. Nelson, who retired in 2020, worked a wide range of assignments during a 25-year career. He described MPD’s paramilitary culture and emphasized the influence of rank and seniority. He said that experienced officers - i.e., Chauvin - would always be in charge of situations. But he also conceded that “I was just following orders” is not a defense, and confirmed that officers are accountable for what they do and fail to do.

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

Trial is scheduled to resume Monday, 2/21.

WRAP - WEEK 4 (prosecution and defense cases)

As the prosecution case came to a close, its final expert, a police chief, re-emphasized the “grossly disproportionate” use of force on Mr. Floyd, criticized the defendants’ failure to intervene despite his clear distress, and dismissed concerns that it would have required officers to use force against their superior. A bystander then closed with a tearful account of Mr. Floyd’s descent into unconsciousness as defendant Thao ignored her protests and busied himself “patrolling and protecting.”

Each defendant is taking the stand. Chauvin’s partner, former cop Tou Thao, testified first. He said that academy instructors taught him to use his knees (a training photo was posted to that effect.) After eight years on the job he had “not seen this much of a struggle.” Mr. Floyd seemed to be on drugs and suffering from excited delirium, so he had to be restrained until EMT arrived. Chauvin used his knee and Mr. Floyd complained that he couldn’t breathe. But if someone can speak, they’re breathing. Thao also assumed that Chauvin, “a 19-year veteran,” knew what he was doing.

J. Alexander Kueng, the most junior officer on scene, testified that senior officers are always in charge and that “the chain of command is not to be breached.” His training about intervening mostly consisted of an example that showed an officer violently assaulting someone. Chauvin, his past field training officer, was “by the book” and highly regarded. Kueng was on probation and Chauvin could get him fired. Kueng said that he had “never struggled as with Mr. Floyd.” Mr. Floyd didn’t seem to be in dire straits. Kueng was trained that if someone can speak they can breathe, and that persons in excited delirium should be restrained until EMT’s arrive. A side recovery position can be used “when it’s safe to do so.”

A retired police chief testified as an expert for the defense. He called MPD’s “duty to intervene” policy simplistic and essentially useless. Kueng had insufficient training and experience to recognize that Chauvin was using excessive force. And as a subordinate he would be expected to defer to his seniors. As for rolling Mr. Floyd over, that can only be done when “safe and practical.” Another defense expert, a retired MPD lieutenant, emphasized the paramilitary aspects of policing and the primacy of rank and seniority. In practice, senior officers are always in charge.

WEEK 5

DAY 17 (2/21/22)

Defense case continues

Defendant Thomas Lane takes the stand. When the episode occurred Lane was on his fourth shift as a full-fledged cop. He had been on about 130 calls while under supervision. Lane knew that Chauvin was a long-time cop, “a guy that had been in a lot of serious situations and could handle himself.”

Lane said that Mr. Floyd, a large man, was at first “out of control.” During the struggle to place him in the police car Mr. Floyd struck his head and started bleeding from the mouth. Lane called an ambulance “Code 2,” meaning non-urgent (that was later stepped up to “Code 3”). Training for excited delirium was to hold someone in place until medics arrived and injected ketamine. Lane suggested using a hobble device, which would have allowed placing Mr. Floyd on his side. But with an ambulance coming Thao didn’t want to complicate things.

Lane didn’t get a close look, but Chauvin’s knee “appeared to be just kind of holding at the base of (Floyd's) neck and shoulder.” Lane said he told Chauvin that he thought Mr. Floyd was in excited delirium. Chauvin replied “that's why we got him on his stomach and that's why the ambulance is coming.” Lane didn’t press the point. But once Floyd stopped resisting he asked “should we roll him on the side?”. Chauvin replied “nope, we’re good like this.” Lane soon repeated his request to roll Mr. Floyd over so they could “better assess” his condition. But Chauvin “just kind of avoided that and asked if we were OK.”

Under cross-examination Lane conceded that he had never before seen an officer use his knee on the neck of someone lying on their stomach. He agreed that the duty to protect and render aid overrode any fealty to a superior. Lane also conceded that after a point he stopped interjecting himself. But he insisted that he thought Mr. Floyd had kept on breathing and was “all right” until he saw his face on the stretcher. Lane teared up as he explained why he accompanied Mr. Floyd into the ambulance. “Just based on when Mr. Floyd was turned over, he didn't look good and I just felt like, the situation, he might need a hand.” He quickly learned that Mr. Floyd was in cardiac arrest.

Trial testimony ends

DAY 18 (2/22/22)

Closing arguments

Prosecution. Assistant U.S. Attorney Manda Sertich said that Chauvin slowly killed Floyd “in broad daylight on a public street.” Yet the accused did nothing. Bystanders realized that Mr. Floyd needed help and demanded that Thao step in. But he mocked the victim, telling the crowd that’s “why you don’t do drugs.” Kueng “laughed” when Chauvin said that Floyd talked a lot for someone who couldn’t breathe. And once Chauvin turned down his requests to roll Floyd over, Lane backed off.

To prove a civil rights violation one must demonstrate the defendants’ “willfulness” - meaning “bad purpose.” That was obvious. “These defendants knew what was happening, and contrary to their training, contrary to common sense, contrary to basic human decency, they did nothing to stop Derek Chauvin or help George Floyd.” Letting someone die so as not to upset a colleague is plainly unacceptable. Intervening is “what we expect from [police officers] as a community, because that's what the constitution demands: To act.”

Defense. Robert Paule, Tou Thao’s lawyer, pointed out that three officers couldn’t get Mr. Floyd in the squad car. Mr. Floyd clearly displayed the “superhuman strength” characteristic of excited delirium. Training that his client received about ExDS depicts officers using their knees on people’s necks as a means of restraint. An ambulance was summoned, and its urgency was soon upgraded. “They didn’t do that for a bad purpose. They did that to get medical people there quickly.”

Tom Plunkett, J. Alexander Kueng’s lawyer, asserted that his client’s training was inadequate. As a rookie, Kueng had no alternative but to rely on his former training officer, Chauvin. “He respected this person. He looked up to this person. He relied on this person's experience.” He also implored jurors to be fair and honest, “the exact opposite of a mob.”

Earl Gray, Thomas Lane’s lawyer, echoed these arguments. He expressed astonishment that his client was even charged (he attributed it to “politics,” and an objection was overruled.) Like Kueng, Lane was a rookie. He “can’t argue with [Chauvin]...that’s common sense...Chauvin was going to be the leader of the pack with these two kids.” Lane had suggested that Floyd be rolled over. But Chauvin didn’t say “maybe.” He said “no.” Paramedics also praised his helpfulness. “Doesn't that show that he was not deliberately indifferent?” protested Gray. “Isn't that substantial evidence?”

Rebuttal by the prosecution. Assistant U.S. Attorney LeeAnn Bell emphasized that once Mr. Floyd was on the on the ground and had stopped resisting - indeed, he soon went unconscious - the continued use of force was plainly unreasonable. Training required that the defendants roll Mr. Floyd on his side. But they didn’t. Lane could have checked Mr. Floyd’s carotid pulse and started CPR. But he didn’t. “This is a crime of failing to do something...They knew what their training was. They knew what they were supposed to do and they didn’t do it.” And there are no “free passes to the Constitution” for being brand-new on the job. “They chose not to take reasonable steps under the law, that is wilfullness...Evil happens when good men do nothing. This happened in part because these men did nothing.”

Jury instructions. Thao and Kueng are accused of “willfully” - meaning, with a “bad purpose” - violating Floyd’s right to be free from unreasonable seizure by failing to prevent the abuse of Mr. Floyd. If jurors agree that Thao and Kueng are guilty, they must also determine, for the purpose of sentence enhancement, whether that failure caused Mr. Floyd’s death. In addition, Thao, Kueng and Lane are charged with willfully depriving Floyd of his right to due process of law by being purposely indifferent to his medical needs.

Verdict (2/24/22)

After deliberating thirteen hours over two days, jurors convicted the defendants as charged. According to Attorney General Merrick B. Garland, the verdict “recognizes that two police officers [Thao and Kueng] violated the Constitution by failing to intervene to stop another officer from killing George Floyd, and three officers [Thao, Kueng and Lane] violated the Constitution by failing to provide aid to Mr. Floyd in time to prevent his death.” For the Justice Department’s concise summary of the evidence and of each officer’s alleged role, click here.

Click here for the complete collection of George Floyd essays

Possible sentences range from one year to life. A sentence enhancement is also likely as jurors determined that the officers’ conduct led to Mr. Floyd’s death. All three defendants were released on bond. No sentencing date has yet been set. Thao, Kueng and Lane will report to Hennepin County court June 13th. for the beginning of their State trial on charges of aiding and abetting murder and manslaughter.

SENTENCES AND UPDATES (scroll)

8/22/24 Thomas Lane, the rookie Minneapolis cop who held down George Floyd’s legs during the fatal May, 2020 encounter, was released from Federal prison after serving concurrent Federal and State terms for violating Mr. Floyd’s civil rights and abetting manslaughter. He will be on State parole for two years. His colleagues, J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao, are serving slightly longer prison terms and will soon be released. Their senior cop, Derek Chauvin, was convicted of murder and drew twenty years. He was transferred to a Texas Federal prison after being stabbed at an Arizona Federal prison last year.

11/30/23 The Minneapolis family that owns the businesses, including Cup Foods, which are located where the encounter with George Floyd took place are suing the city for curtailing police response to what’s now called “George Floyd Square.” Keeping cops away, they claim, has led to a great increase in crime and “made the area so dangerous that it has become known as the ‘No Go Zone’.” Meanwhile, Tou Thao, the cop who watched over the spectators to Mr. Floyd’s abuse, has appealed his Federal civil-rights conviction to the Supreme Court because he allegedly lacked the required “willfulness.”

8/18/22 Ex-MPD cop Thomas Lane will report to a Federal prison camp near Denver on August 30 to serve his 2 1/2 year Federal term. FCI Englewood, a low-security institution, has previously hosted former Il. Gov. Rod Blagojevich and former Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling.

7/29/22 George Floyd’s family and their advocates have strongly criticized the perceived leniency in the Federal prison terms handed out to Derek Chauvin’s colleagues, which were below Federal guidelines and lower than what prosecutors recommended. Judge Paul Magnuson’s decision was apparently influenced by the fact that Lane and Kueng were rookies, and that Thao, who wasn’t, was nonetheless “a good police officer, father and husband.” But that, said a local activist, should have had no bearing.