|

Posted 7/23/21

RACIAL QUARRELS WITHIN POLICING (PART II)

In San Francisco, White cops allege that color and gender do count

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. In Part I we discussed a Federal lawsuit filed by Black and Hispanic police officers who serve in a Maryland county nestled against the nation’s capital. As it happens, their action, which accuses officials of “fostering a climate of discrimination against non-White officers and retaliating against those who dare object,” has a counterpart on the opposite shores.

Its plaintiffs, though, are sixteen White, Asian and Assyrian cops. Filed in April 2020, the newest (third) version of their complaint (the first, in June 2019, had thirteen accusers) alleges that their superiors have for years engaged in “a pattern of promoting lower-scoring candidates” in Sergeant, Lieutenant and Captain exams. In contrast with Prince George’s County, the “primary beneficiaries” of the City of San Francisco’s bias are Blacks and females.

Click here for the complete collection of resources, selection & training essays

An interesting aspect of the complaint is that its introductory section leans on two prior studies: one by the city, another by the Feds, examining allegations of racism and homophobia at SFPD. Those inquiries were prompted by the discovery that White officers (yes, White) had exchanged text messages berating Black persons, including fellow cops, as well as members of the city’s vibrant LGBT community. In 2016, San Francisco’ “Blue Ribbon Panel,” formed by then-D.A. George Gascon, issued its report. While its tone was decidedly reform-minded, it did note that White officers’ chances of advancement had been on a years-long downtrend (p. 58). Concern was also expressed about the potential for favoritism; test results notwithstanding, moving up in rank seemed essentially at the Chief’s pleasure: An interesting aspect of the complaint is that its introductory section leans on two prior studies: one by the city, another by the Feds, examining allegations of racism and homophobia at SFPD. Those inquiries were prompted by the discovery that White officers (yes, White) had exchanged text messages berating Black persons, including fellow cops, as well as members of the city’s vibrant LGBT community. In 2016, San Francisco’ “Blue Ribbon Panel,” formed by then-D.A. George Gascon, issued its report. While its tone was decidedly reform-minded, it did note that White officers’ chances of advancement had been on a years-long downtrend (p. 58). Concern was also expressed about the potential for favoritism; test results notwithstanding, moving up in rank seemed essentially at the Chief’s pleasure:

“The absence of rules governing the selection of promotional candidates and the discretion held by the Chief, along with the lack of programs offering support to those seeking promotions, raises the likelihood of bias or favoritism in promotion decisions.” (p. 57)

Two correctives were suggested:

- “The SFPD should institute a high-level hiring committee to sign off on the Chief of Police’s final hiring decisions, including deviations from the standard hiring and training process.” (p. 60)

- “The Police Commission should create and implement transparent hiring and promotions processes and criteria, including a requirement that every candidate’s disciplinary history and secondary criteria be considered.” (p. 60)

San Francisco also asked the COPS technical assistance center to come in. Aside from examining allegations of racial bias, it also looked into the use of deadly force. On first glance its conclusions don’t seem particularly favorable for the plaintiffs. COPS pointed out that White officers constituted 49 percent of the force in 2015. Yet they represented 59 percent of Sergeants, 51 percent of Lieutenants and 67 percent of Captains (p. 187). Still, it noted that during 2013-2015 the proportion of Whites being promoted receded, while the share of minorities moving up increased (p. 194). At the same time, a lack of “transparency” in the promotional process, which had also been noted by the Blue Ribbon panel, “created a level of distrust” (p. 202). So COPS recommended that SFPD “clearly outline the qualifications required to advance.”

Of course, if the city presses for the advancement of women and minorities, while the promotional process remains opaque, White prospects could indeed become victims of discrimination. That possibility, which lies at the core of the White officers’ lawsuit, wasn’t addressed by either the Blue Ribbon panel or by COPS.

This isn’t the first time that San Francisco’s cops have sued. In 1973 Black officers filed a Federal lawsuit alleging that race and gender discrimination hindered their hiring and promotion. Six years later, after considerable litigation, the city entered into an elaborate consent decree that set goals for hiring women and minorities and directed that efforts be made to promote them “in proportion to their representation in the qualified applicant pool.”

Unfortunately, Blacks didn’t succeed in adequate numbers. Accordingly, in 1984 SFPD adjusted the relative weights of its promotional exams (there are several, written and oral) so that minorities and women would qualify for a greater share of vacancies. Notably, that happened after the scores came in. White officers sued. While a Federal district judge discounted their objections, in 1989 the Ninth Circuit held that the post-facto rebalancing was unlawful. San Francisco agreed that tweaking things after-the-fact was wrong and promised to stop.

But when SFPD resumed administering exams, minorities again wound up under-represented. So with approval from the Feds the city adopted a “banding” process. Exam scores were grouped into ranges, and within each promotions were awarded using secondary criteria such as commendations and awards. A modest number of slots were also set aside for women and minorities. Again, White officers sued. This time, though, the city prevailed. In November 1992 the Ninth Circuit called banding a “unique and innovative” way of “addressing past harms to minorities while minimizing future harmful effects on nonminority candidates” and gave it its blessing.

According to the current plaintiffs, that “flexibility” became a smokescreen for a complex and opaque promotional system whose overriding objective is the advancement of women and minorities. In their view, things promptly went downhill. In 2003 and 2004 twelve White sergeants filed three Federal lawsuits alleging illegal discrimination in the 1997 lieutenant’s exam. Their actions were ultimately settled in 2008 for $1.6 million.

In 2007 disaster supposedly struck White prospects again when the city administered a “multi-part” Captain’s exam comprised of “a series of written and oral exercises.” But instead of simply promoting applicants according to their scores, SFPD adopted a “Rule of Five” approach:

“...the eligible list would consist of the officers with the five highest exam scores [“Rule of Five”] plus an additional officer -- that is, the next highest scorer -- for each additional vacancy that the City sought to fill...Thus, if the City were seeking to fill three vacancies during a given round of promotions, the seven highest-scoring officers would be placed on the eligible list.”

That gave decision-makers considerable flexibility. And that wasn’t all. Once an officer made the list, the promotional criteria changed:

“Any vacancies that arose at the captain position during the next thirty-six months would be filled by candidates selected from that list by the Chief of SFPD (or his or her designee) based on a variety of ‘secondary criteria’...These criteria would include the candidate’s past ‘assignments, training, special qualifications, commendations/awards, bilingual certification, and discipline history’...”

Neither was the “Rule of Five” a sure bet. From the start, the city cautioned that “if there is adverse impact under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 resulting from the Rule of Five Scores, then a broader certification rule shall be used...” And once exam results were in, things did change:

“In January 2008, the City...announced that it no longer planned to use the Rule of Five Scores to fill all of the captain vacancies that arose over the next thirty-six months...Rather, it would use the Rule of Five Scores to fill the first eleven vacancies and, for all subsequent vacancies, would use a different process known as ‘banding’...Banding places less emphasis...on an applicant's score ranking by treating all exam scores that fall within a ‘statistically derived confidence range’ [the band] as functionally equivalent...”

That “band” was of substantial width:

“For the 2007 captain's exam, the City elected to use a ‘band of 45 points . . . starting with Rank 16’ to fill any vacancies that arose after the first eleven vacancies...This band included the fourteen officers who achieved the sixteenth through twenty-eighth highest scores on the exam...In addition to these officers, the City would also continue to consider the applications of the four higher-ranked officers who were not selected for one of the first eleven promotions under the Rule of Five....”

Two White candidates, Lieutenants Heinz Hofmann and Thomas Buckley, earned “the sixteenth and twentieth highest scores” on the exam. So “neither was eligible under the Rule of Five Scores for any of the first eleven vacancies.” Problem is, once they became eligible, both got passed over under “banding.” In 2011 the list expired, and they sued. In 2015, a Federal judge denied both sides summary judgment. San Francisco eventually settled for $200,000.

Back to the present. What’s alleged in the current lawsuit?

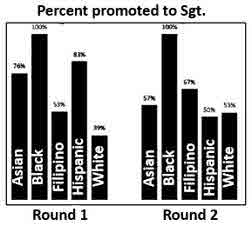

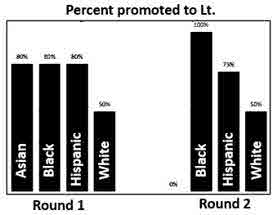

- Seven patrol officers claim they are being denied promotion to Sergeant because they are White males; an eight because he is an Assyrian male; and a ninth because he is an Asian male. According to the complaint, the 2017 list invoked a “Rule of 10,” allowing decision-makers to skip ten scores below that of the last successful candidate. So far, every Female officer and every Black officer on the list have been promoted. But only 46 percent of White officers have succeeded, and that’s held true despite the fact that they comprise 63.5 percent of the candidate pool (Sgt. graph. appears on the complaint.)

- A Rule of 10 is also being used to fill vacancies from the still-current 2017 Lieutenant’s list. While only one Black applicant scored among the top thirty, and the top-ranked female was 52nd, every Black candidate and every female has succeeded. However, only half of the White officers on the list have gained promotion. Four sergeants claim that they have been denied advancement because they are White males, and a fifth “because she is a White lesbian” (Lt. graph appears on the complaint.)

- That Rule of 10 is also being applied to the (still active) 2015 Captain’s list. Two Lieutenants claim they are being denied promotion to Captain because they are White males. One, whose score placed him twelfth, claims that he was passed over in favor of Black, Asian, Hispanic and female candidates whose scores were as many as twenty-six places lower.

Full stop. There can be valid race and gender-blind reasons for passing over applicants no matter their test scores. For example, one of the current plaintiffs, Lieutenant Ric Schiff, was once disciplined for insubordination and neglect of duty. That, according to then-police Chief George Gascón, explains why he skipped over Schiff for Lieutenant over a decade ago. Schiff and others nonetheless sued. And as mentioned above, the city settled. (Schiff reportedly got a tidy $200,000 after lawyer’s fees. )

San Francisco is undeniably a very “woke” place. Politics and ideology likely affected the work of the Blue Ribbon Panel. They’ve certainly characterized the career of its convener, George Gascón. A former San Francisco police chief, later its chief prosecutor, his criticism of “vast racial disparities in arrests and prosecutions” likely helped him win the D.A.’s race last year in another progressive burg, the “City of Angels.” A staunch opponent of long prison terms, Gascón quickly prohibited deputies from using sentence enhancements. That set off an unprecedented revolt by assistant D.A.’s who recoiled at the thought of going easy on violent offenders. It also sparked a recall campaign. And while Gascón has drawn support from LAPD chief Michel Moore, in these violence-impacted times his future is far from assured.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

So is manipulating the promotional process the only way to help minorities succeed? We think not. Thomas Boone, the Black Lieutenant who leads the charge in the Prince George’s County lawsuit, once observed that White officers are more likely to occupy specialized assignments where they gain the “skills, training and experience” that helps them score well on promotional tests. Race aside, how can street cops land a specialized slot? In our law enforcement experience, that often comes from doing quality work, and particularly by cranking out great reports that catch the eye of superiors, who often only know employees from what they read. To be sure, improving one’s written expression can take time and effort, but the payoff is invaluable.

Still, in these ideologically fraught times, when many cops feel compelled to line up by race and gender, solutions that emphasize quality work may seem a touch blasé. So by all means, keep fighting against bias. But don’t forget about the craft of policing. In the end, that’s what really counts.

UPDATES (scroll)

10/3/24 Settling a long-running dispute with the Justice Department, Maryland has agreed to revamp its hiring practices for State Police applicants. It will modify its written entrance exam, which DOJ said discriminated against Blacks, and the physical fitness test, which reportedly discriminated against women. Past applicants who were needlessly disqualified will be recompensed; up to twenty-five will be hired. (See 7/16/22 update)

7/6/23 Bernard Robins, a Black man, joined the LAPD in 2019. Three years later he quit. His leaving came on the heels of a stop and search by White LAPD officers who observed a Black man drop a closed bag into Robins’ parked car. Robins refused consent to search, but the cops did so anyway and found drugs and a “ghost gun” in the bag. Police arrested the man - he was supposedly a cinematographer with whom Robins was preparing a film - but the D.A. refused to prosecute. Robins, who claims that the agency chronically mistreated him because of his race, has now filed suit. Civil complaint

7/16/22 Following allegations of discrimination against Black applicants and officers already on the job, DOJ announced it has launched a “pattern or practice” investigation into the hiring and promotional practices of the Maryland State Police. (See 10/3/24 update)

6/8/22 Maryland’s Police Accountability Act (click here), which incorporates citizen panels into the police disciplinary process, will take effect in July. But Prince George’s County is still quarreling over the details. Although eleven citizens have been vetted to serve on its Police Accountability Board, residents complain they were excluded from the selection process. And the power the nominees would actually yield is considered insufficient.

5/13/22 Former Minneapolis deputy police chief Art Knight will be paid $70,000, and former officer Colleen Ryan will receive $133,600 to settle claims of discrimination. Mr. Knight, a Black man, said he was demoted in 2020 because he accused the city of discriminating against minorities when hiring cops. Ms. Ryan, who is lesbian, claims that her advocacy for gender non-conforming officers led to unending harassment in the agency’s “misogynistic and homophobic culture.”

9/23/21 Ten Black females, each a current or former D.C. police officer, filed a Federal lawsuit accusing the agency of “degrading” and discriminating against Black female officers and engaging in “repeated, coordinated and relentless retaliation” whenever they dared complain. According to the complainants, the agency’s EEO staff identified them as “troublemakers” and was part of the problem.

9/17/21 With time and money running out and only 200,000 of the required 580,000 voter signatures on hand, recall backers suspended their effort against George Gascon, L.A.’s progressively-minded new D.A. But they vow to be back. Gascon’s moves to end cash bail and prohibit assistant D.A.’s from seeking death penalties and sentence enhancements angered crime victims and many of his own deputies.

9/8/21 Now a postal employee and mother of two, an Illinois woman claims she was rejected from her dream job as a Chicago cop because she admitted, during the hiring process, to a couple poor moves as a youth: depositing a bad check, and under-charging a friend at a drug store. Such things, according to the Tribune, contribute to an under-representation of Blacks in the ranks: while they constitute 30 percent of the city’s residents, only 20 percent of its cops are Black. Hispanics are equally represented at 29 percent, while Whites, who form 33 percent of the city, are over-represented at 47 percent.

8/6/21 New York PD published a highly detailed “Equal Opportunity Policy” employee handbook that affirms all employee decisions will be made without regard to any of a host of individual characteristics. Among these are age, citizenship status, color, race, disability, gender identity and sexual orientation.

7/23/21 Chicago PD’s special “merit promotion system” is back. Implemented in the 90’s to advance more minorities and “ambitious officers who do not test well on promotional exams,” it was dropped by prior Chief Charlie Beck who feared it allowed favoritism. Chicago PD’s new superintendent, David Brown, just brought it back. His intent, to “diversify the ranks” at a time when trust in police is lacking, was recently reflected in the promotion to lieutenant of seven Blacks, one Hispanic and one White.

7/11/21 On June 9 six Black Los Angeles City Fire Dept. arson investigators filed a State lawsuit alleging that they were abused by a “good old white boys club” of White men who have “very racist and bigoted attitudes and do not believe in diversity, equity or inclusion in the workplace.” According to the plaintiffs, their complaints of mistreatment, including unfair denial of promotions, were not investigated. Instead, they led to “adverse employment actions” including “false allegations of workplace misconduct.”

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Racial Quarrels Within Policing (I) Not all Cops are Blue

Posted 7/11/21

RACIAL QUARRELS WITHIN POLICING (PART I)

In Maryland, Black and Hispanic cops complain that color does count

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Tucked against the District of Columbia, Prince George’s County, Maryland (est. 2019 pop., 900,327) is one of the more affluent majority-Black counties in the U.S. With a population that’s 64.4 percent Black, 19.5 percent Hispanic and 12.3 percent White, its median household income of $84,920 is more than a third higher than the nation’s $62,843, while its poverty rate of 8.7 percent is substantially lower than the nation’s 10.5 percent. These economic blessings are reflected in the county’s relatively modest crime rates. According to the UCR, in 2019 (the most current year) Prince George’s violent crime and homicide rates (220.3 and 5.6) were substantially lower than Maryland’s (454.1 and 9.0) and compared favorably with the U.S. overall (379.4 and 5.0.)

Click here for the complete collection of resources, selection & training essays

Would that Prince George’s relative tranquility extend to its cops! On December 12, 2018 the Black and Hispanic police officer associations and twelve officers, each Black or Hispanic, filed a Federal lawsuit accusing the County, the police chief, two deputy chiefs and the commander of the police department’s internal affairs unit of fostering a climate of discrimination against non-White officers and retaliating against those who dare object. White officers, who form the majority of the agency, were also accused of using improper and excessive force against citizens and of stealing department funds and property with impunity.

According to the highly detailed, sixty-five page complaint, White officers habitually engage in “vicious racist acts” and use racial slurs and racist imagery to create a “hostile work environment” for Blacks and Hispanics. But whenever victimized officers of color dare raise an objection, their complaints are either ignored or lead to undeserved discipline, undesirable assignments or lost promotional opportunities. For example:

- Captain Joseph Perez, who leads the Hispanic officers association and “has been an outspoken critic of discrimination and retaliation within the PGCPD” complains that “bogus charges” have kept him from advancing in rank to Major. Meanwhile, “less qualified White Captains” have been promoted.

- Lieutenant Thomas Boone, who leads the Black officers association alleges that he was involuntarily transferred from a specialized assignment to patrol as “retaliation for his involvement in filing the complaint.”

- Sergeant Paul Mack, vice-president of the Black officers association, asserts that he was involuntarily transferred when he complained of being cursed at by a White Lieutenant. His promotion to Lieutenant was also denied although he was just as qualified as White applicants who successfully advanced in rank.

Police chief Hank Stawinski, a veteran White officer who served his entire law enforcement career at Prince George’s County resigned in June 2020. His departure coincided with the plaintiffs’ announcement that they would soon release specific, detailed accounts of actual instances of discrimination. These weren’t long in coming. Retired Los Angeles County Assistant Sheriff Michael E. Graham, a plaintiffs’ expert witness, soon filed a 100-page-plus report. Taking PGCPD to task for investigating fewer than fifteen percent of complaints, he furnished numerous examples of racial harassment, names and all. Here are three (we edited them for brevity and left out officer names):

- “A complaint was filed against officers Police Officer---, Sergeant--- and Sergeant--- for exchanging racist text messages and saying things like “we should bring back public hangings,” and making misogynistic comments about female Black officers. There is no indication...that this matter was investigated...”

- “Corporal--- made a series of negative comments about Black people, including that ‘at least slaves had food and a place to live’ and referring to President Obama as a ‘coon.’ Cpl--- also defended the Ku Klux Klan and equated the Black Lives Matter Movement with the KKK...there is no indication...that this matter was investigated...”

- “In response to a communication to the Department announcing the establishment of the United Black Police Officers Association in August 2016, numerous senior white officers sent derogatory responses, including Lt.--- and Major---. There is no indication...that any of these officers were ever investigated.”

According to Mr. Graham, even when inquiries take place they’re half-hearted. Hampered by a lack of confidentiality or other protections, complainants are routinely exposed to retaliatory transfers, denials of promotion and baseless counter-charges. For example:

- “In 2015, Cpl.--- [a Black male] filed several complaints against his [White] supervisor, Lt.---. One such complaint alleged that Lt.--- had called a civilian a ‘project n****’. In October 2016, Cpl.--- was suspended with pay and transferred...without any explanation. His request for a hearing was denied. Cpl.--- subsequently learned that his transfer was a result of Lt.--- filing an IAD [Internal Affairs] complaint against him for allegedly interfering with an [unrelated] investigation...IAD does not appear to have investigated Lt.--- for retaliation, and there is no evidence Defendants opened an investigation into Cpl.---’s complaints about Lt.---‘s racist conduct.”

Even in the rare instances when violators are held to account, the penalties are laughable. For example:

- “...an African-American training instructor showed a slide depicting a white police officer pointing his gun at a Black man while a citizen recorded the incident. When the instructor asked the officers what the slide depicted, Cpl.--- responded...‘that’s that Black Lives Matter crap.’ Plaintiff [a lieutenant] took offense to this comment [and] was ordered to leave the classroom, and he complied. Following this, Cpl. contacted her superior officers with false statements about the incident and filed a charge alleging that [the plaintiff] charged towards her...The Department notably did not require Cpl. to complete any racial sensitivity training, nor did the Department charge her with using discriminatory language or repeating the same false statement to other [officers]...”

Mr. Graham also reported that Black officers are more severely disciplined. Although they comprise 42.8 percent of the force, they account for 54 percent of punishments and 71.4 percent of terminations or resignations. For example:

- “While on duty [a Black female officer] returned to her vehicle and found that her firearm had been stolen. She was suspended pending investigation, fined $500 and received a written reprimand...The discipline records produced by PGCPD contain several instances in which white male officers reported their firearms lost under similar or worse circumstances—none of them were disciplined as severely [or] suspended pending investigation.”

Lieutenant Boone’s declaration uses data collected by the county’s Police Reform Working Group. It noted that while there are about the same number of Black cops (661) as White (653), the latter are vastly over-represented in the upper ranks. In 2020 there were fifty-six White lieutenants versus twenty-five Black; twenty-five White captains vs. six Black; and thirteen White majors vs. only nine Black. (Deputy Chiefs were evenly split at two each, and the interim police chief was Hispanic.) Lt. Boone feels that this lopsided distribution creates “a self-perpetuating cycle where white officers have become entrenched in more powerful, more prestigious, and higher paying jobs.” White cops, he notes, are far more likely to be assigned to specialized units where they gain valuable “skills, training and experience” that helps them advance in rank. These assignments also give them “far more time to study for promotional exams” than working patrol, which is where most Black cops wind up. Police Reform Working Group. It noted that while there are about the same number of Black cops (661) as White (653), the latter are vastly over-represented in the upper ranks. In 2020 there were fifty-six White lieutenants versus twenty-five Black; twenty-five White captains vs. six Black; and thirteen White majors vs. only nine Black. (Deputy Chiefs were evenly split at two each, and the interim police chief was Hispanic.) Lt. Boone feels that this lopsided distribution creates “a self-perpetuating cycle where white officers have become entrenched in more powerful, more prestigious, and higher paying jobs.” White cops, he notes, are far more likely to be assigned to specialized units where they gain valuable “skills, training and experience” that helps them advance in rank. These assignments also give them “far more time to study for promotional exams” than working patrol, which is where most Black cops wind up.

Perhaps predictably, the defense’s four main experts vigorously endorse PGCPD’s selection and promotion practices:

- Retired police chief J. Thomas Manger and Dr. Janet R. Thornton strongly challenge assertions of bias in discipline and promotion. Here’s an extract from Mr. Manger’s rebuttal of plaintiff Perez’s assertion that the charges against him were “bogus”:

“Plaintiff Perez filed a request with the Circuit Court for Prince George's County requesting a ‘Show Cause’ hearing to determine whether Prince George's County Police Department's actions in the investigation were retaliatory...Prince George's County Maryland upheld the AHB's findings, stating that...‘any reasoning mind can find [Plaintiff Perez's conduct] to be intimidating.’ The court further found that Plaintiff Perez ‘use[d] the prestige of [his] office to gain access and ultimately to gain personal benefit....’ As a result of his actions, Plaintiff Perez received a demotion from Captain to Lieutenant, and was removed from the promotion cycle for one year.”

- Dr. John J. Boland strongly disputes that transfers and failures to promote caused actionable economic damage. He dismissed claims by Lt. Thomas Boone, who was promoted but transferred from specialized duties to patrol, and by Sgt. Paul Mack, who was on a promotion list that expired, that they were thus deprived of the opportunity to earn substantial amounts of overtime pay. Dr. Boland argued that being compensated for overtime “is not guaranteed, is subject to many factors, and is in no sense an entitlement. Any calculation of lost overtime pay is necessarily speculative.”

- PGCPD’s promotional process includes multiple-choice exams and skills assessment centers. Dr. Toni S. Locklear fully supports their validity. She blasted the plaintiffs’ experts as lacking the background to evaluate the agency’s promotion and selection process and called their analyses of the PGPD's “racial makeup” and “Corporal Exam Passing Rates” deeply flawed. Dr. Locklear also criticized her rivals’ failure to acknowledge a “voluminous case record” that, in her view, confirms the integrity of PGCPD’s methods.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Clearly, the final chapter is still being written. But PGCPD’s undeniable racial disparities within its upper ranks are tough to defend. To prevent continued injury to Black and Hispanic officers, this April the Court issued a preliminary injunction ordering that the agency appoint “an independent expert” to analyze the promotional process and recommend changes. Promotion lists generated under the old system cannot be used after August. (For its reasoning, which relies in great part on the disproportionate number of Whites in supervisory and management positions, click here.)

Well, that’s (more than) enough for now. Next time we’ll switch shores to that notoriously liberal bastion of San Francisco. That’s where White cops have stood this story on its head. Yup, they’ve also sued, and for much the same reason as their Black counterparts in Maryland. We’ll then close out with a few words about the consequences of such quarrels on those who pay for – and presumably rely on – all that good police work. We mean, of course, the public.

UPDATES - See Part II

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Racial Quarrels Within Policing (II) Not all Cops are Blue

Posted 2/8/21

A RISKY AND INFORMED DECISION

Minneapolis P.D. knew better. Yet it hired an applicant, then kept him on.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Say you’re a...police chief. Your agency, like many others, requires that officer applicants take the MMPI, a popular psychological assessment test that uses several hundred yes/no questions to screen persons for mental problems. Responses are compared against a 2,000-officer national sample. If they’re too far from the norm, it’s time for second thoughts!

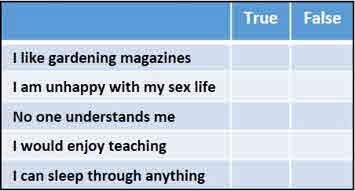

Here’s how prosecutors retrospectively summarized a certain police applicant’s results on the MMPI (specifically, the MMPI-II-RF):

...he reported disliking people and being around them...[T]he test results indicate a level of disaffiliativeness that may be incompatible with public safety requirements for good interpersonal functioning. His self-reported disinterest in interacting with other people is very uncommon among other police officer candidates...he is more likely to become impatient with others over minor infractions...He is also more likely...to exhibit difficulties confronting subjects in circumstances in which an officer would normally approach or intervene....

Knowing all this, would you have hired him? Minneapolis did. After interviewing the would-be cop, a psychiatrist told human resources not to worry. While Mohamed Noor’s MMPI scores did seem extreme, they didn’t jibe (“correlate”) with positive information that came from other sources. And there was no indication that the applicant was mentally ill.

Click here for the complete collection of resources, selection & training essays

Thus reassured, Minneapolis police hired Mr. Noor in 2015. Fast-forward to February 1, 2021. That’s when the Minnesota Court of Appeals affirmed his conviction for third-degree murder in the death of Justine Ruszczyk. Officer Noor shot her dead on July 15, 2017, when he had about two years into the job. We wrote about this horrific episode soon after the tragedy. Little was then known about the officer’s temperament and suitability for policing. Since then, the laborious, revealing process of trial and appeals has bridged that gap. And that’s what brings us here.

First, let’s briefly recap the incident. While at home, Ms. Ruszczyk heard a woman screaming outside. It sounded like a sexual assault, and she promptly dialed 9-1-1. Other citizens had apparently done the same. She then noticed that a police car was parked nearby. (Having seen nothing, its officers were about to drive away.) Ms. Ruszczyk approached the vehicle and apparently slapped its trunk to draw attention. That startled its two occupants. Officer Harrity, the driver, drew his gun and supposedly pointed it at the floor. But his partner, Officer Noor, promptly fired, inflicting a fatal wound.

Officer Noor was suspended, then fired. Eight months later prosecutors charged him with second-degree murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. They accused him of behaving unreasonably and demonstrating “extreme indifference to human life”:

The defendant failed to sufficiently investigate a series of 911 calls in the area that night...showed no interest in investigating the circumstances that were potentially dangerous to the subjects of the 911 calls or the public in general...took no time at all to make any inquiry into who approached his squad car and wholly failed to determine whether she actually posed a danger to him or anyone else...rather than try to deescalate the situation or slow it down in any way, the defendant went right to his gun and intentionally shot and killed the 911 caller outside his car.

Those words were part of a request to introduce as evidence Noor’s pre-employment psychological test, the commonly-used MMPI (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory). While the court denied the motion, it let two policing experts take the stand. They testified that Noor’s performance that evening had been “contrary to generally accepted policing practices” and that his use of lethal force was “objectively unreasonable” and “violated police policy, practices, and training.”

But prosecutors weren’t satisfied. They were eager to paint a broad picture of Noor’s unsuitability as a cop:

The defendant...proved to have trouble confronting subjects in situations where an officer is supposed to intervene, controlling situations, and demonstrating a command presence. The defendant’s work history proves that he overreacts, escalates benign citizen contacts, does not safely take control of situations, and, in the most egregious situations, uses his firearm too quickly, too recklessly, and in a manner grossly disproportional to the circumstances.

This required they go beyond what happened on one fateful evening. During his brief career Noor had been the subject of three formal citizen complaints. There was also an active lawsuit alleging that he needlessly injured a citizen during a routine call. These episodes were apparently admitted (Noor’s lawyer reportedly brought them up first.) But the court refused to allow a wholesale recounting of the defendant’s work history. Here are examples of what didn’t get in (click here for a news account):

- During a traffic stop about two months before he shot Ms. Ruszczyk, Noor pointed his gun at the head of a driver who made a crude gesture at a bicyclist with whom he apparently nearly collided. The driver contested the citation; Noor failed to appear at the hearing and the ticket was dismissed.

- About a year earlier, as Noor finished his probationary period, one of his field training officers (FTO) expressed strong reservations about the rookie’s fitness for duty:

He was in the final ten days of training...On the eighth day...the defendant's FTO wrote that the defendant did not want to take calls at times. While police calls were pending, the defendant drove around in circles, ignoring calls when he could have self-assigned to them.

- Another FTO reported that Noor had promised a 9-1-1 caller that he would look for a possible burglar who was knocking on residents’ doors. But he didn’t:

...instead of doing that [Noor] got back into his car and left the area. The FTO later stated that it mattered to her that the defendant said one thing and did another because police should “do our due diligence on this job, so it's important that you at least try to look around. You never know if that person’s in the area.” She also said 911 callers tend to believe the police when the police say they are going to look for somebody.

- FTO’s also mentioned that Noor exhibited “tunnel vision” and had serious problems managing stress, to the point “that he sometimes missed radio communications from dispatch.”

For the jurors it was mostly about that one night. In an in-depth, post-verdict interview, a panelist said that the jury wasn’t convinced that Noor wanted to kill. So it acquitted Noor of second-degree murder, which requires that specific intent. In fact, until nearly the conclusion of the trial they were also split on the other counts:

Until they put it at the end with their two expert witnesses, I didn’t really find the prosecution to be beyond a reasonable doubt. Their two expert witnesses really resonated. Just the fact two police officers, even though they don’t work in the Minneapolis Police Department, are testifying against another police officer, I think that resonated pretty well. I don’t know if everyone in the jury room had the same opinion, but we definitely felt that there is a blue wall of silence in some sense.

What ultimately sold them? Noor’s recklessness in opening fire:

It was unanimously concluded that Harrity [the driver] was dangerously close to being shot as well. Combined with the fact that Noor failed to properly identify a threat lead us to decide that the entire act was so reckless to everyone in that line of the bullet there really wasn’t any way to say it wasn’t. It’s such an egregious use of firearms at such a basic fundamental level that you wouldn’t even think of ever doing that except in the case of the most absolute dire circumstances in which you would have no other choice.

Jurors convicted Noor of third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter on April 30, 2019. One week later he was sentenced to twelve and one-half years imprisonment (maximum on the murder count is twenty-five years.) As for the appeal, the two prevailing justices let the convictions stand as-is, while the third only affirmed for manslaughter. Noor’s case is on appeal to the state Supreme Court, and we’ll keep track. But we’re not trying to split legal hairs. Considering that MMPI, should Noor have been hired? And considering his performance, should he have been retained?

Ms. Ruszczyk’s killing generated attention from the mental testing community. Within a few months American Public Media published a comprehensive analysis of MPD’s psychological screening process. Its assessment was far from favorable:

There is no way to know whether Noor's psychological makeup played a role in the shooting, or if so, whether any screening could have detected such a tendency. But the screening protocol the city put Noor and 200 other officers through during the past five years is less extensive than the battery of tests used in comparable cities. It's also less rigorous than national best practices and the screenings Minneapolis administered for more than a decade before.

APM’s reviewer objected to the agency’s sole use of the MMPI (most agencies employ a battery of tests) and the qualifications of the psychiatrist in charge of the process, who supposedly knew little about policing. His firm, in fact, was soon let go, supposedly because it had consistently disqualified a disproportionate number of minority applicants. But APM had little positive to say about his replacement.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Still, as MPD’s then-psychiatrist noted, there was plenty of “positive information” about Mr. Noor. He had a B.A. in business administration and had been gainfully employed for years. What’s more, Noor was a Somali immigrant and spoke the language fluently. Minneapolis has a large and vibrant Somali community, and MPD hosts a Somali-American police officer association that seems well-known throughout law enforcement circles (for news articles about its work click here, here and here.) So Noor’s presumed ability to relate to minority citizens was undoubtedly welcome.

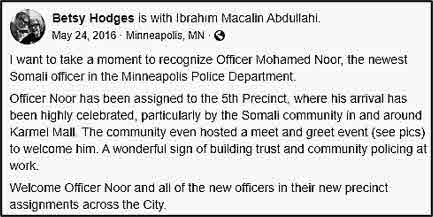

Indeed, the new rookie’s arrival at his first post, the Fifth Precinct, was celebrated with a party. Here’s Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges’ Facebook post commemorating the occasion. But a brief two years later, the warmly-received cop’s downfall caused great consternation and soul-searching. (For news accounts click here, here and here.) Indeed, the new rookie’s arrival at his first post, the Fifth Precinct, was celebrated with a party. Here’s Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges’ Facebook post commemorating the occasion. But a brief two years later, the warmly-received cop’s downfall caused great consternation and soul-searching. (For news accounts click here, here and here.)

Had Noor’s promising ethnic background nullified concerns about his MMPI score? Did it push aside misgivings about deficiencies in his attitude and performance? It’s possible. Yet attributing poor hiring and retention decisions to ethnicity is a fraught undertaking. Check out one of our very first posts, “What Should it Take to be Hired?” Skip to “Officer 3.” Although as an applicant he conceded having a lousy temper and repeatedly striking his wife, his selection was approved by the department psychologist. Same-o, same-o, “Officer 4.” Once they were on the job both became key players in LAPD’s notorious “Rampart” misconduct scandal of the late nineties. (Most of those cops were White. At the time LAPD used the MMPI and the California Personality Inventory to screen applicants. For LAPD’s report click here.)

Problem is, some agencies have seemingly granted cops a virtual license to abuse. Grab a look at “Third, Fourth and Fifth Chances” and related posts. Don’t skip “Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job,” our account about another Minneapolis tragedy, the death of George Floyd. His antagonist, nineteen-year MPD veteran Derek Chauvin, started accumulating citizen complaints in 2003, two years into the job. By the time he leaned on Mr. Floyd’s neck there had been eighteen. Only two led to discipline, both minor slap-downs for “using demeaning language.” Had MPD’s managers been more attuned to their officers’ conduct, and more willing to impose correctives, Mr. Floyd and Ms. Ruszczyk would still be alive.

And our troubled, deeply polarized land might feel like a different place.

UPDATES (scroll)

5/30/23 Chronic understaffing plagues police departments and sheriffs offices across the U.S. Last year Illinois reported that sixty percent of its law enforcement agencies were understaffed, and that nearly one in five had shortages exceeding ten percent. Such dilemmas have led managers to raise the bar when deciding whether and how severely to punish officers, and to significantly lower it when making hiring decisions. Misbehavior that would normally result in firing is being overlooked, and lowered entrance requirements and academy standards have allowed poorly-qualified candidates to join the force.

9/9/22 According to the Alameda County, Calif. Sheriff’s Dept., rookie deputy Devin Williams, Jr., 24 had “no red flags” when hired a year ago. He previously worked as a Stockton, Calif. cop but for undisclosed reasons failed its field training program during his rookie year. He’s now under arrest for murdering his married girlfriend and her husband. His mother said she had warned her son against the relationship. Alameda authorities say they were unaware of the circumstances that led to the violence.

1/15/22 A Chicago police officer still on his initial 18-month probationary period has been arrested for attempted murder after shooting and wounding three persons during a “drunken brawl” in a bowling alley. Kyjuan Tate, 27 reportedly opened fire after he was punched. Another account reports that the brawl began when customers intervened in a dispute between Tate and his girlfriend. His prior disciplinary record includes a 30-day suspension while working as a probation officer and an “altercation” with a restaurant patron during his police graduation party, which led to police being called.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Watching the Watchers Third, Fourth and Fifth Chances Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job

Three Shootings What Should it Take to be Hired?

|