|

Posted 2/8/24

WRONG PLACE, WRONG TIME, WRONG COP

Recent exonerees set soul-wrenching records for length of wrongful imprisonment

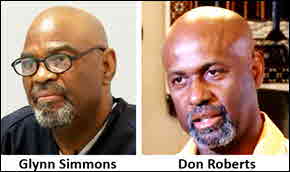

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. “There never really was any real evidence. Just being a Black kid in the wrong place at the wrong time.” That’s how lawyer John Coyle explained how his client, Mr. Glynn Simmons, came to be wrongfully convicted for murdering an employee and wounding a customer during the December 30, 1974 armed robbery of an Edmond, Oklahoma liquor store. Mr. Simmons, a 22-year old resident of Louisiana, and his alleged crime partner, Don Roberts, a 21-year old who lived in Texas, were charged with the crime two months later. Their arrest was based on their identification by a customer who viewed them during a live lineup. Belinda Brown, then 18, had been shopping for tequila and was wounded during the holdup.

Mr. Simmons and Mr. Roberts wound up in that lineup in a most unorthodox way. Robberies had beset Edmond. Several weeks after the liquor store holdup police obtained a confession from a local man to two other robbery-murders. He and his brother, whom police suspected of being a helpmate, had recently attended a party in Oklahoma City, and officers sought to identify everyone present. It so happened that the get-together took place at the residence of Mr. Simmons’ aunt, who lived in Oklahoma. Mr. Simmons, who had recently relocated from Louisiana, was there. So was Mr. Roberts, with whom Mr. Simmons was then unacquainted.

Click here for the complete collection of wrongful conviction essays

There were actually two witnesses to the liquor store robbery: Ms. Brown and an employee who came through unscathed. At first, neither offered much promise. Ms. Brown complained that “...if I waited much longer” she wouldn't be able to remember the robbers’ faces because “it would get all jumbled up in my mind and it wouldn't be the same.” And the employee said that she froze on the robbers’ guns and would be unable to recognize their faces.

More than a month later police staged eight live lineups of persons who attended the party. According to a police report that was withheld from the defense, Ms. Brown identified six persons, including Mr. Simmons, Mr. Roberts, and the recently confessed murderer, as being the (two) perpetrators. Ms. Brown conceded she was uncertain and said that she “wanted to think about the identification ‘overnight’.”

No matter. By the June, 1975 trial date Ms. Brown had become certain that Mr. Simmons and Mr. Roberts were the bandits. Although her original description of Mr. Simmons as large and corpulent was way off (he's a small man), she confidently identified both defendants in court.

Mr. Simmons’ primary defense was the testimony of four Louisiana-based friends who confirmed that he was still living there when the Edmond robbery took place. But two other friends weren't called, and affidavits from five others never came into play. (Mr. Simmons’ lawyer was disbarred years later for poor performance, although apparently not over this case.) Indeed, Ms. Brown's identification constituted the sole evidence of the defendants’ guilt. But she must have impressed jurors, as it took them only a bit over two hours to convict Mr. Simmons and Mr. Roberts. That shocked the prosecutor. He later conceded being troubled by the manner in which they were identified: “…quite candidly, it was one of the few cases I have been involved in that the verdict a week later could easily have been different.”

But it wasn’t. Mr. Simmons and Mr. Roberts wound up on death row. Fortunately, a state supreme court ruling about the death penalty reduced their punishment to life without parole. Don Roberts was paroled in 2008 after serving 33 years. Mr. Simmons, though, remained behind bars. Ultimately it was that secret, damning police report that made the difference. And, as well, the implication, backed by a comparison of gun calibers, that the man who confessed to the robbery-murders and his brother were the real culprits. damning police report that made the difference. And, as well, the implication, backed by a comparison of gun calibers, that the man who confessed to the robbery-murders and his brother were the real culprits.

In April, 2023 the Oklahoma County D.A. petitioned for Mr. Simmons’ release over a “Brady” violation, meaning the State’s failure to reveal exculpatory information. On July 23, 2023, after serving “forty eight-years, one month and 18 days,” Mr. Simmons was released on bond. And in December a judge ruled that there was “clear and convincing evidence” of Mr. Simmons’ innocence and absolved him altogether. Want more? “A State of Denial,” the September 13, 2021 episode of Investigation Discovery’s “Reasonable Doubt” reality-TV series, is about this case.

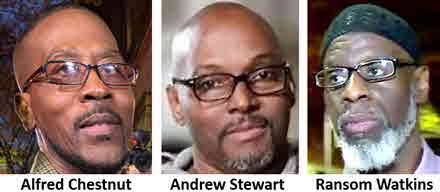

“On behalf of the criminal justice system, and I’m sure this means very little to you, I’m going to apologize.” On November 25, 2019, thirty-six years after their imprisonment for shooting and killing a 14-year old boy, Alfred Chestnut, Andrew Stewart and Ransom Watkins were declared innocent and freed. Judge Charles Peters’ move was hardly controversial. After all, it had been sought by Baltimore's chief prosecutor, Marilyn Mosby, who agreed with innocence project attorneys that the case had been deeply flawed from the start:

I’m sorry. The system failed them. They should have never had to see the inside of a jail cell. We will do everything in our power not only to release them, but to support them as they re-acclimate into society.

Just how that “failure” came to be involved two chronic causes of wrongful conviction: police pressure on eyewitnesses, and, as in the case of Glynn Simmons and Don Roberts, the withholding of key evidence. It’s not that police had little to go on. After all, the killing, whose objective was supposedly to steal the wearer's desirable Georgetown University jacket, took place during class hours. And the three defendants – they were then sixteen, and each was a former student – happened to be at the school visiting. What’s more, when approached by police, Chestnut was wearing just such a jacket.

But Chestnut and his friends denied any involvement. As for the jacket, the youth claimed it had been a gift (his mother later confirmed it with sales receipts). A school security guard also said that, before the killing took place, he escorted the three visitors outside and locked the door. But the focus on them persisted. On two successive days police showed a photo lineup to two of three boys who had been walking with the victim. (One wasn't there when the killer approached, and the other two ran off when he drew his gun.) None identified any of the three. But one did pick out another youth, 18-year old Michael Willis, whom the security guard observed across the street after the killing.

Still, Chestnut, Stewart and Watkins remained very much in the cross-hairs. We know nothing about their reputation, nor why they had switched to a different school. Their behavior, though, did get them kicked out on that fateful day. And there was that jacket. Officers soon struck gold. A fourth student said that she saw the shooting take place and identified the three from the lineup. And when  the original set of witnesses was brought back for a third go-around, they confirmed it. What's more, the youth who picked out Michael Willis said he only did so because Willis was “from the neighborhood.” Case solved! the original set of witnesses was brought back for a third go-around, they confirmed it. What's more, the youth who picked out Michael Willis said he only did so because Willis was “from the neighborhood.” Case solved!

At trial a defense investigator testified that two of the prosecution's witnesses told him that the accused was not involved. Another reportedly claimed that he was told not to speak with the defense. Defense lawyers also brought in three students whose accounts contradicted the prosecution's version of events. One said that he saw two other boys try to take the victim's jacket. But Michael Willis, whom authorities now believe was the killer, was unmolested. And after accumulating a substantial arrest record, he was himself murdered in 2002.

Why did “the system” fail Glynn Simmons, Don Roberts, Alfred Chestnut, Andrew Stewart and Ransom Watkins? And, as our “Wrongful Conviction” essays have reported, so many others? Let’s self-plagiarize from “Damn the Evidence - Full Speed Ahead!”:

When serious crimes aren’t promptly resolved, pressures mount from within and outside the ranks, to say nothing about forces within oneself. That’s when “confirmation bias,” the natural tendency to “interpret events in a way that affirms one’s predilections and beliefs” rears its ugly head. Should detectives fall prey, they may accept “evidence” that might otherwise seem sketchy or implausible (“House of Cards” and “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”). And as our guardians rush along, pressuring witnesses and turning “no” and “maybe” into “yes”, what’s inconsistent gets disputed or is simply ignored (“Can We Outlaw Wrongful Convictions II”). Indeed, that’s how a “house of cards” gets built (“The Ten Deadly Sins”).

Eyewitness identification – that is, mis-identification – was a key factor in both cases. In past decades, “separating the wheat from the chaff” was, even more so than today, a matter of all-too-fallible human judgment. Thirty-plus years ago DNA was “in its infancy.” And there were no video cameras recording everyday life. Assessing the accuracy of citizen observations was wholly left to the cops. Naturally, detectives are under pressure to solve crimes, and especially crimes of violence. Sometimes, though, there are several potential evil-doers. Stir in that nasty, all-too-human predilection for “confirmation bias,” and it really does create “A Recipe For Disaster”.

We can’t get into the heads of the officers whose misfires cost innocent men decades in prison. But journalists who dug deeply into the second example claim that Baltimore's detectives had fomented a deviant, reckless subculture that relied on coercion and intimidation to get witnesses to go along. Still, what shapes the initial decision to pick on, say, Jack instead of Bob? In our experience “on the street,” such choices are often influenced by suspects’ criminal records. Alas, what we've read about these cases doesn't mention whether the innocents had previously tangled with the law. And it gets trickier. Consider the first case. Edmond's cops had recently corralled an admitted armed robber. He and his brother are now believed to have committed the liquor store murder. Why weren't they targeted from the very start? Could it be because eyewitnesses didn't pick them out?

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Detectives often face complexities. After all, that’s what “detecting” is all about. Alas, when they encounter a “whodunit”, the pressures of the job - after all, they do have other cases - can provoke a move to simplify things. Yet all kinds of policing are complex. Consider the ambiguities and lack of compliance that patrol officers encounter every hour of every day. What's the solution? quality policing, meaning a craftsmanlike approach to the job. It’s definitely not (and must not be) about “making numbers”. That can generate disasters such as wrongful convictions. Or, turning to other demanding occupations, cause airplane parts to fly off mid-air. Here’s what a retired Boeing engineer said about the recent 737 Max-9 imbroglio:

…I would argue that the most like scenario is that the employees felt rushed, and employees were feeling rushed because the corporation is pressuring the factories to produce these planes and pump them out the door.

Alas, productivity is often relied on, in policing and elsewhere, to evaluate performance. Want to read more about the influence of the “numbers game” on policing? Download “Production and Craftsmanship in Police Narcotics Enforcement”. And let us know what you think!

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES

Production and Craftsmanship in Police Narcotics Enforcement

RELATED POSTS

Craft of Policing special topic

Damn the Evidence - Full Speed Ahead! A Recipe For Disaster Guilty Until Proven Innocent

House of Cards Can We Outlaw Wrongful Convictions II The Ten Deadly Sins

|