|

Posted 12/23/17

ACCIDENTALLY ON PURPOSE

A remarkable registry challenges conventional wisdom about

the causes of wrongful conviction

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. “Your Lying Eyes,” one of this blog’s very first posts, related the stories of three victims of crime. Each was done in not by a crook but by the State. Lousy policing and indifferent prosecution in North Carolina, Rhode Island and California had led to the mistaken arrest and wrongful conviction of Ronald Cotton, an innocent man who wound up doing eleven years for rapes he did not commit, and Scott Hornoff and David Allen Jones, who were exonerated after serving six and nine years respectively for murder.

One could argue that their endings were more-or-less happy. After all, both Hornoff (a police detective) and Jones had been on track to do life. It’s harder to rejoice about the outcome for many other exonerees. For example, consider Craig Coley, whose November 2017 pardon by California Governor Jerry Brown took thirty-nine years to come to pass. And it’s well-nigh impossible to celebrate the ultimate redemption of Cameron Todd Willingham, whom Texas executed in 2004 for setting a house fire that experts now agree was accidental.

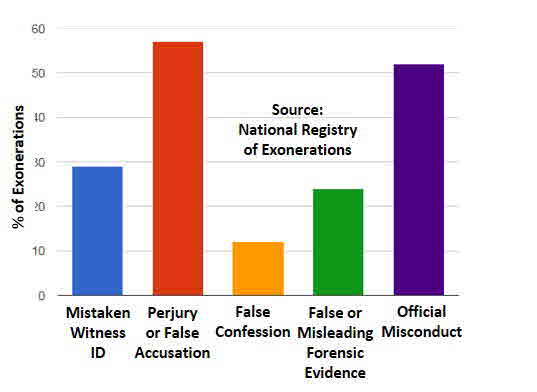

Miscarriages of justice are definitely not going away. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, which tracks such things back to 1989, there have been 681 exonerations during the past five years, including eight-eight in 2013, 135 in 2014, 165 in 2015, 169 in 2016 and 124 so far in 2017. Exonerations are coded as to one or more of six causes: mistaken witness ID, false confession, perjury or false accusation (someone other than the defendant lied), false or misleading forensic evidence, official misconduct (govt. officer significantly abused their authority), and inadequate legal defense.

Click here for the complete collection of wrongful conviction essays

Except for Willingham, whose official rehabilitation seems unlikely (can you expect Texas to apologize for a wrongful execution?) each of the others mentioned above appears in the Registry. It attributes the conviction of Cotton to mistaken witness ID; of Jones to a false confession; and of Coley to misleading biological evidence. But ex-cop Hornoff’s case is one of three in 2003, when eighty-one exonerations were recorded, for which no cause is reported. (There have been sixty-nine such cases since 2013, about ten percent of the total.)

Apparently there are causal factors that the registry doesn’t measure. To help fill the gap we offer our favorite: confirmation bias. In “Guilty Until Proven Innocent” we defined it as the tendency to “interpret events in a way that affirms one’s predilections and beliefs.” When making decisions fallible humans are always shoving aside niggling inconsistencies and seizing on solutions that reflect their biases, predilections and beliefs. Naturally, in policing the consequences of taking shortcuts can be disastrous. Here’s an extract from our earlier account about Hornoff:

On August 12, 1989, Warwick, Rhode Island police discovered the body of Vicki Cushman, a single 29-year old woman in her ransacked apartment. She had been choked and her skull was crushed. On a table detectives found an unmailed letter she wrote begging her lover to come back. It was addressed to Scott Hornoff, a married Warwick cop. Hornoff was interviewed. He at first denied the affair, then an hour later admitted it. Detectives believed him and for three years looked elsewhere. Then the Attorney General, worried that Warwick PD was shielding its own, ordered State investigators to take over. They immediately pounced on Hornoff. Their springboard? Nothing was taken; the killing was clearly a case of rage. Only one person in Warwick had a known motive: Hornoff, who didn’t want his wife to find out about the affair. And he had initially lied. Case closed!

Although several witnesses placed Hornoff elsewhere at the time of the killing, his lie apparently doomed him with jurors. He’d still be locked up except that the killer had a conscience. Incredible as it may seem, the real perpetrator eventually turned himself in and confessed.

Wait a minute. Didn’t forensics promise a future free of wrongful conviction? As it turns out, physical evidence is often lacking, and even when it’s present it may not be collected or properly handled. Cotton, Jones and Coley would have never been convicted had officials realized that the materials they gathered actually carried the perpetrators’ DNA. On the other hand, inexpert application of forensic techniques can make things worse – much worse as the Willingham imbroglio illustrates. Indeed, according to the Registry, thirty-six of the 124 wrongful convictions recorded in 2007 (a full twenty-nine percent) are partly or wholly attributable to forensic goofs. It’s not just subjective techniques such as handwriting examination and dog-scent evidence that can cause problems. Sophisticated methods including ballistics, serology and even DNA have also been blamed for “identifying” the wrong person. We recently discussed a move by the Department of Justice to prevent such blunders by regularizing the work of Federal forensic scientists (click here and here). Unfortunately, it seems that politics may have doomed this effort. (For an authoritative assessment of the state of the forensic art check out the National Research Council’s landmark 2009 report, “Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward.”).

What can be done to combat miscarriages of justice? We must recognize that some cops, lab employees and prosecutors are careless, take dangerous shortcuts and habitually seize on convenient solutions. And that agencies have fostered such tendencies by emphasizing and rewarding numerical productivity. “What counts” must not simply be “what’s counted.” As our blog has repeatedly warned, one cannot champion crude measures such as number of arrests and expect that employees will exercise good judgment in the field – or the lab.

Still, we’ve always assumed that mistakes which underlie wrongful convictions are usually errors in judgment. But according to the Registry, more than half the blunders this year cross the line into something more. So far in 2017, official misconduct – meaning, on purpose – figures as a cause or contributor for seventy-nine of 124 wrongful convictions. That’s a full sixty-four percent. (Perjury/false accusation trailed just behind with seventy-seven exonerations. Inadequate legal defense was a factor in forty-nine, false or misleading forensic evidence in thirty-six, mistaken witness identification in thirty-two and false confessions in twenty-six.)

For a stunning example of how far policing can fall look up this year’s alphabetically first victim of official misconduct: Roberto Almodovar, whose wrongful conviction is attributed to witness coercion by Chicago detective Reynaldo Guevara. According to the Registry, and to a recent, eye-popping article in the Chicago Sun-Times, this was only the latest in a long string of episodes of alleged “bullying” by Guevara. So far his handiwork has resulted in seven exonerations and, in 2009, a stunning $20 million civil award to one of the victims. (By the way, Guevara recently took the Fifth, and by that we don’t mean booze.)

Sad to say, this isn’t the first time that a Chicago detective has come under fire for such things. In 2010 the Feds convicted one-time Chicago police commander Jon Burge “for falsely denying in an earlier civil suit that in the 1980s he and his officers extracted confessions through beatings, electric shocks and suffocation.”

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

And it’s not just the cops. Check out “People do Forensics” and “Better Late Than Never”:

The Justice Department and FBI have formally acknowledged that nearly every examiner in an elite FBI forensic unit gave flawed testimony in almost all trials in which they offered evidence against criminal defendants over more than a two-decade period before 2000….The cases include those of 32 defendants sentenced to death. Of those, 14 have been executed or died in prison, the groups said under an agreement with the government to release results after the review of the first 200 convictions.

Well, there’s no need to bully readers: our point’s been made. Many miscarriages of justice aren’t “accidents”: they’re the product of willful misconduct. Yet regardless of the justification for using shortcuts – whether it’s to assure that offenders are punished, or something more self-serving such as pleasing superiors and gaining recognition – taking the low road is simply wrong. As a quick glance through the Registry reveals, in criminal justice it’s also apparently quite common. And until that is openly acknowledged, innocents will suffer while the guilty remain free to continue their predations.

UPDATES (scroll)

8/13/24 In the New York Times, an in-depth video series features three death row prisoners whom the editorial board believes are innocent. The final, third installment pertains to Texas prisoner Charles Don Flores, who has been on death row 25 years. Flores, who has always protested his innocence, was convicted of murder on the basis of his identification by a female witness after she underwent hypnosis, a technique that’s now banned. Detectives assertedly “linked” Flores to the murder vehicle, then allegedly coached the woman relentlessly. With Flores’ execution pending, his lawyers plan to file a “last ditch request” for a new trial. But it’s considered “a long shot.” Amicus Brief

5/16/24 Chicago man Gerald Reed did thirty years for killing two men in 1990. But in 2021 Illinois’ Governor commuted his sentence due to concerns that Reed’s confession was extracted through torture ordered by notorious one-time Chicago PD Commander Jon Burge. Reed was released. But although he couldn’t be sent back to prison for the murders, he was just retried. And a jury found him innocent. Still, he remains locked up. Reed committed a robbery in Indiana soon after he was freed the first time. That got him ten years, a term that he’s still serving. His lawyer, though, warns that a lawsuit is coming. (See 10/26/22 update)

4/11/24 Homeless and troubled, William Woods gave up. In 2020 he pled guilty in Los Angeles to a series of financial crimes. Woods was jailed, then placed under mental care. In fact, the crimes had been committed by Matthew Keirans. A long-ago coworker, he had stolen Woods’ identity and posed as him since 1988. Finally, in 2023, a detective at the Iowa college where the pretend Woods worked used DNA from Woods’ father’s birth certificate to confirm who the real Woods was. Keirans recently pled guilty to Federal impersonation charges; he faces thirty years. Woods’ exoneration is pending.

3/22/24 According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 153 persons were exonerated of their criminal convictions during 2023. Eighty-six were exonerated of murder, and two for manslaughter. Twenty-three were exonerated of other violent crimes, and 17 for sexual assault. Fifty exonerations were based at least in part on mistaken eyewitness ID, 32 on false confessions, and 116 on perjury or false information. False or “misleading” forensic evidence was cited in 43 cases. National Registry

6/15/23 In 1988 Chicago man Arthur Brown drew a life sentence for murdering two persons by arson. During his trial he insisted that his confession was coerced by police. Years later his account was seconded by a fellow inmate, who said he set the fire. Brown was retried, but jurors disbelieved his witness, and he was again convicted. In 2017, after Brown had served 29 years, a judge found fault with his prosecution and ordered a third trial. But newly-elected progressive D.A. Kim Foxx dismissed the case and Brown was released. Chicago has now agreed to pay him $7.25 million compensation.

5/26/23 It was a horrendous crime - the attempted gunning down of six L.A.-area high school students. Three gang members were convicted in 1990 and received lengthy terms. In 2017, one told the parole board that he was the shooter and that one of those convicted, Daniel Saldana, told the truth when he denied being present. But his words weren’t passed on to the D.A. for six years. When they were, things moved swiftly. Acting on the D.A.’s motion, a judge declared Saldana innocent. He had served 33 years.

4/17/23 Former Chicago D.A.’s Nick Trutenko and Andrew Horvat face prosecution for lying about a material issue connected with the 2020 retrial of Jackie Wilson, who had been imprisoned, along with his brother Andrew, for murdering two Chicago police officers in 1982. That investigation was one of many tainted by allegations that detectives working under notorious ex-cop Jon Burge had coerced confessions. Andrew Wilson was retried, reconvicted, and died in prison in 2007. But in October 2020, after serving 36 years, Jackie Wilson was exonerated. (Note: Indictments have been returned charging both former prosecutors with offenses including perjury, official misconduct and obstruction.)

11/28/22 According to a new report by the National Registry on Exonerations, innocent Black persons are approx. “seven-and-a-half times more likely to be convicted of murder” than innocent Whites. Contributing to the disparity is the far higher rate of murder in areas populated by Black persons. Innocent Blacks are also more than eight times more likely than innocent Whites to be convicted of rape. And because “racial profiling” leads them to be stopped far more often, innocent Black persons are also disproportionately convicted of drug crimes.

10/26/22 Illinois Governor J. B. Pritzker commuted Gerald Reed’s sentence last year because his conviction for a 1990 murder stemmed from work by detectives supervised by disgraced former Chicago P.D. Commander Jon Burge. But promptly on release, Reed reportedly embarked on a multi-State “crime spree.” So now he’s back in jail, but for other things. Meanwhile the saga of his original case remains. Could he be retried for the murder? And if he’s convicted, could he do more time? (See 5/16/24 update)

9/28/22 A major study about racial disparities in wrongful conviction by the National Registry of Exonerations concludes that Black persons “are seven times more likely than white Americans to be falsely convicted of serious crimes.” In homicides, many wrongful convictions arise from pairing slipshod policing, officer misconduct, racial bias and the weaknesses of cross-racial identification with the high rates of violence that characterize areas predominantly populated by Black persons.

8/10/22 Announcing that she “can no longer stand by these convictions,” Chicago D.A. Kim Foxx dismissed charges against seven persons convicted at the hands of discredited former police detective Reynaldo Guevara. Thirty-one convictions resulting from his “work” have been overturned since 2016, with causes ranging from “manipulating witnesses to fabricating evidence.” Those freed included Carlos Andino, who was serving a 60-year term, and Johnny Flores and Jaime Rios, who had been imprisoned for two decades. More exonerations are promised.

7/15/22 With prosecutors’ assent, a Chicago judge freed two brothers who served 25 years in prison for a murder they insist they did not commit. Juan and Rosendo Hernandez were allegedly picked on by disgraced former detective Reynaldo Guevara at the behest of former cop Joseph Miedzianowski, who thought that one of the brothers stole drugs from an associate. Miedzianowski is serving a life sentence for drugs and racketeering. As in Guevara’s other cases, the brothers’ conviction stemmed from questionable witness identifications.

7/13/22 After serving twenty-six years for a murder he insists he did not commit, Jose Cruz is a free man. Released yesterday after a judge threw out his conviction, he joins the expanding list of victims of discredited former Chicago cop Reynaldo Guevara. At trial, one witness identified Cruz as the killer, but it’s alleged he was coached. There were two other witnesses, but both insisted the killer was Black, so neither was called. Similar circumstances tainted the convictions of Daniel Rodriguez, who was exonerated earlier this year, and of David Colon, who was released in 2017 but could be re-charged.

4/26/22 Released in 2006 after spending thirteen years in prison, Daniel Rodriguez is now truly “free.” Cook County prosecutors dismissed his murder conviction, which had been based on Mr. Rodriguez’s confession to disgraced ex-Chicago P.D. detective Reynaldo Guevara. Mr. Rodriguez claims he was not involved in the crime, and that he only confessed because he was beaten by Guevara and his partner.

4/23/22 Every challenged conviction - with forty-four just tossed, the number is now two-hundred twelve - “related” to the work of corrupt former Chicago P.D. Sergeant Ronald Watts has been dismissed. Several of his victims were present when a Cook County judge vacated their convictions. In 2012 an FBI sting led to Watts’ conviction for extorting drug dealers and residents of a housing project and pressing phony charges. He served 22 months in prison. One colleague was also convicted. But several officers who knew of Watt’s wrongdoing remain on the job, although without police powers.

2/17/22 Ex-Chicago cop Ronald Watts left Federal prison in 2015, but the exonerations of those he and his corrupt colleagues arrested on phony drug charges keep coming. Last summer lawyers for 88 defendants petitioned for the dismissal of 100 convictions. Nineteen were just granted, bringing the total to 59. Prosecutors are doing individual reviews, and more dismissals are likely (see 12/16/20 update).

1/22/22 Chicago is considering a $14 million settlement to compensate Kevin Bailey and Corey Batchelor, two wrongfully convicted men who spent decades in prison for a 1989 murder that was investigated by associates of disgraced former detective Jon Burge. Their convictions were tossed out in 2018. Burge died that year after serving 4 1/2 years in Federal prison and home confinement.

9/16/21 Two Chicago men, Armando Serrano and Jose Montanez, will share $20.5 million for being “framed” in a 1993 murder by retired police detective Reynaldo Guevara. In 2004 a witness said his testimony against them was “fed” by the now-infamous detective, who allegedly bullied and coached winesses as a matter of course. In all, eighteen convictions in which Guevara played a role have been tossed. One was settled by the city for $21 million in 2009; another for $17 million in 2018.

8/27/21 Twelve years into his career, Adewale Oduye called it quits. One of L.A.’s few Black prosecutors, his many attempts to keep cops from railroading the innocent had run into a brick wall. And within his office a culture of race and sex discrimination didn’t help. He began posting about it all online. In time, though, “Spooky Brown” got found out. Now he works with at-risk youths.

7/1/21 After serving thirty-six years for killing a police officer, Jackie Wilson was awarded a certificate of innocence. His exoneration came after three trials, most recently last fall. In the end, defenders proved that Wilson’s brother was the culprit, and that Jackie Wilson’s confession was extorted by a gang of cops led by notorious police commander Jon Burge. Wilson, who was released in 2018, is preparing a massive lawsuit. A special investigation into alleged prosecutorial misconduct has been ordered.

12/16/20 In 2012 an FBI sting led to the arrest and conviction of former Chicago police Sgt. Ronald Watts and Officer Kallatt Mohammed, who during a “decade of corruption” extorted drug dealers and residents of a housing complex and allegedly pressed phony charges. Their activities led to the exoneration of fifteen persons in 2017 alone. So far eighty persons convicted through their testimony have had their charges dismissed, with the most recent eight coming yesterday.

4/6/19 Posted at the Innocence Project, an interview with Jennifer Thompson, whose mistaken witness ID led to the wrongful conviction of Ronald Cotton. Thompson now leads an organization that advocates for exonerees.

2/24/19 Simi Valley, CA, whose officers once wrongly concluded that Craig Coley was a killer, agreed to settle his claim for $21 million. That’s on top of the $1.95 million that California paid Coley for its role in imprisoning him for 38 years for a murder he didn’t commit.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED WEBSITE

Race and Wrongful Convictions in the United States, 2022

RELATED POSTS

Damn the Evidence - Full Speed Ahead! A Victim of Circumstance Why do Cops Lie?

People do Forensics Guilty Until Proven Innocent Better Late Than Never

Wrongful and Indefensible The Tip of the Iceberg One Size Doesn’t Fit All No End in Sight

The Witches of West Memphis False Confessions DOJ to Texas Baby Steps Never Say Die

NAS to CSI Would You Bet House of Cards Can We Outlaw Wrongful Convictions?

The Usual Suspects Labs Under the Gun Your Lying Eyes

RELATED ARTICLE

Quantity and Quality

Posted 3/19/17

GUILTY UNTIL PROVEN INNOCENT

Pressures to solve notorious crimes can lead to tragic miscarriages of justice

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. “Confirmation bias” denotes the tendency to seek out information and interpret events in a way that affirms one’s predilections and beliefs. A notorious example of how such biases can affect the criminal justice process is the case of David Camm. In September 2000, four months after Camm retired as an Indiana trooper, his wife and two children were shot to death. Camm alerted 911 after allegedly finding their bodies when he returned home from an evening out. He was arrested and convicted for the killings and served thirteen years, going through three trials before being ultimately acquitted. At his last trial, in 2013, a defense witness, Dr. Kim Rossmo, an expert on cognitive bias in criminal investigations, blamed factors including confirmation bias and “groupthink” for leading detectives and prosecutors to overlook contradictory evidence, ignore DNA and rely on a deeply flawed interpretation of bloodstain evidence in their rush to judgment.

An appeals court reversed the first verdict, ruling that introducing evidence of Camm’s extramarital affairs was unduly prejudicial. Before the second trial DNA that authorities said they had sent in (but did not) was finally tested. It was found to match Charles Boney, an ex-con who had done time for armed robbery. Boney had also left his palmprint at the crime scene. He wound up testifying against Camm, to the effect that he provided the murder weapon but waited outside the home while Camm executed his family. A forensic “expert” testified that victim bloodstains on Camm’s shirt had been produced by spatter, and three prisoners insisted that Camm confessed to the killings.

Camm was again convicted (Boney would be separately tried and convicted. He drew life without parole.) But this conviction was also reversed, as Boney had been allowed to testify, without corroboration, that Camm admitted molesting his daughter.

Click here for the complete collection of wrongful conviction essays

Camm’s third trial, held in 2013, brought in a wholly new perspective. A defense expert testified that Boney’s DNA was found on the clothes and under the fingernails of Camm’s wife, thus putting the lie to his claim that he “waited outside.” Dr. Rossmo and another expert, who testified at length, criticized the investigation as haphazard and hopelessly biased from the start. Most importantly, the self-styled “serologist” who testified about blood spatter on Camm’s clothes was thoroughly discredited. Real experts, hired by the defense, testified about the profound ambiguities and uncertainties of blood spatter analysis and said that the traces of victim blood found on Camm’s clothes were likely produced by accidental transfer when he found the bodies.

Camm was acquitted. His lawsuit against the county was settled in 2016 for $450,000. Camm’s litigation against D.A.’s and State police investigators continues.

David Camm’s saga drew extensive coverage in the broadcast media, including 48 Hours and WDRB TV, and has several extensive writeups online (click here for the Wikipedia page and here for Murderpedia.) His travails are also cited in a forensic science text and were the subject of two nonfiction works (click here and here). And if that’s not enough, a novel that closely tracks the case is supposedly in the works.

When actionable leads are lacking detectives may have little choice but to assemble a list of possible evildoers. As we suggested in “The Usual Suspects”, getting arrested increases one’s risk of being accused of offending in the future. And when the new crimes are particularly grave – say, a string of unsolved rapes – pressures to bring a culprit to justice can rope in anyone who seems to fit the bill.

That’s the situation that Luis Lorenzo Vargas faced in 1999 when Los Angeles Police proudly announced the arrest of “The Teardrop Rapist.” Suspect of at least thirty-nine sexual assaults between 1995 and 2013, the rapist (he reportedly had a pair of teardrop tattoos under his left eye) stalked central city streets during the early morning hours and threatened victims with a gun or knife before dragging them away.

Vargas lived in the area where the rapes occurred and physically resembled the perpetrator down to a teardrop tattoo under the left eye (Vargas, though, only had one.) His past was also highly damning, as he had served three years in prison for the 1992 rape of a girlfriend. Detectives investigating three sexual assaults between February and July 1998 attributed to the Teardrop Rapist showed the victims a photospread that included Vargas. Each victim would ultimately identify him as her assailant, although with qualifications and what now seems considerable uncertainty.

Police arrested Vargas in July 1998. He was tried eleven months later. Each accuser positively identified him in court, and Vargas was convicted. What the prosecution didn’t disclose was that despite his arrest the rapes continued.

Vargas steadfastly denied his guilt and drew 55 years. He thereafter continued to maintain his innocence, placing parole out of reach. Finally, in 2012, thirteen years into his term, the California Innocence Project secured a court order to have the rape kit from one of the three victims submitted for DNA analysis (physical evidence was not available for the others.)

DNA testing excluded Vargas. But they matched several other assaults attributed to the Teardrop Rapist. Prosecutors recommended that Vargas be exonerated and a judge concurred. Vargas was released on November 23, 2015 after serving more than sixteen years. Meanwhile the “real” Teardrop Rapist remains unidentified.

External and self-induced pressures to solve heinous crimes can lead even the best intentioned investigators to set aside doubts and interpret information in a light most favorable to a prompt resolution. Camm and Vargas were likely suspects who bobbed up in a sea of complexities that might have taken a very long time to untangle. But the criminal justice system doesn’t have centuries.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Of course, no good cop would knowingly arrest and no good prosecutor would knowingly seek to convict the wrong person. Yet workplace pressures can play havoc with evidentiary practices. Camm was done in by misleading forensic testimony procured by police and prosecutors from a pretend expert. Vargas fell to the perils of eyewitness identification. When showing photospreads, investigators can slip and suggest, through word and gesture, just who the “real” suspect is. After undoubtedly many “thank you’s” and words of support, three victims who were once not so certain positively identified an innocent man in court.

DNA helped rescue Camm and was key to Vargas’s redemption. Now consider all the miscarriages of justice where there was no DNA. For more on that, click here.

UPDATES (scroll)

8/23/24 Scott Peterson’s death sentence for the 2002 murder of his wife and their unborn child was overturned in 2020, and he’s now doing life without parole. But he insists that he’s innocent, and his protestations that no physical evidence connect him with the crimes have drawn the support of the L.A. Innocence Project, which moved to have fifteen pieces of evidence analyzed for DNA. A judge, though, has ruled that only one - a section of duct tape - must be tested. Peterson also regrets not testifying at his trial. But he’s trying to make up for that, with personal appearances in two recent documentaries. (See 10/26/22 update)

11/28/23 Waves of murder convictions accompanied the crack wars of the nineties. In time, many were successfully challenged by innocence projects that sprang up to counter the unholy effects of a hurried, imprecise and occasionally corrupt police response. Nationwide there have been 1,300 murder exonerations since 1989, including 115 in New York City. Its two most recent beneficiaries are Jabar Walker and Wayne Gardine. Walker’s accuser recanted, but his change of mind was ignored. Gardine’s accuser, a self-serving drug dealer, originally described the killer as a six-footer. Gardine is five-eight.

10/23/23 In 1983 a Baltimore middle-school student was gunned down for his Georgetown jacket. Although some witnesses said that 18-year old Michael Willis ran out of the school and tossed a gun, police focused on ex-students Alfred Chestnut, Andrew Stewart, and Ransom Watkins because they were kicked out of the school during an unauthorized visit just before the murder. After harsh questioning, several teens ID’d them from a photo spread, and they were convicted in 1984. More than 30 years later an innocence project stepped in, and the three were exonerated and freed in 2019. Baltimore has agreed to pay them $48 million. As for Michael Willis, he was murdered in 2002. Innocence project

(See 12/4/19 update)

9/26/23 In 1987, after a psychiatrist tipped police about Shawn Melton’s depraved fantasies, Solano County, CA police arrested Melton for the assault and murder of a six-year old boy. Melton denied involvement, and he spent nineteen months locked up as juries twice acquitted him. Melton was free but remained a suspect, He died in 2000. Advanced DNA techniques recently absolved Melton and identified Fred Cain, 69, as the real killer. He was arrested by police in Oregon.

4/6/23 Florida man Crosley Green had spent 28 years behind bars for murder when, in 2018, a judge vacated his conviction because prosecutors withheld evidence that the killer was the victim’s girlfriend. Three witnesses recanted as well. But Green stayed locked up until 2021, when he was placed on home detention because of the pandemic. Since then appellate decisions have proven unfavorable to his cause, and after two years of “freedom” Green has been ordered back to prison to complete his life term.

1/25/23 Hawaiian native Ian Schweitzer is a free man. Twenty-five years after he, his brother and a

friend were imprisoned for the rape-murder of a tourist, DNA evidence conclusively established his innocence. Their fate was

sealed by a false admission from the friend, who was trying to mitigate charges in another case, perjured testimony from a

like-minded jailhouse informant, and since-disproven bite-mark evidence. Advances in DNA now conclusively prove that a

blood-soaked t-shirt central to the case, plus the victim’s vaginal swab, plus numerous other key items carries the DNA of

the real killer.

11/18/22 Shamel Capers was sixteen when he allegedly gunned down a rival New York City gang member in 2013. He has always denied guilt, and after serving eight years of a fifteen-to-life sentence a judge set him free. Lael Jappa, the gang member whose testimony was key in convicting Capers, has since repeatedly admitted - including in a recorded phone call to his mother - that he lied to get a break on other charges. And the Queens D.A. said that “we could not let miscarriages of justice stand.”

10/26/22 Remember Scott Peterson? Convicted of his wife’s murder two decades ago, his saga has been depicted in books, movies and documentaries. California’s high court threw out his death sentence in 2020. Its ruling, which cited juror bias, also hinted that bias might have tainted the original verdict. Indeed, did he murder Laci Peterson? It’s now up to a judge to decide whether the case will be retried. (See 8/23/24 update)

8/1/22 Toforest Johnson has been on death row 24 years for murdering a Jefferson Co. (Ala.) deputy. According to his many notable defenders - and that includes a former Alabama Chief Justice, the former State Attorney General, the current D.A. and a juror - the case against him was made up from whole cloth. Yet despite requests by the present and former D.A.’s, no new trial is on the horizon. Website

4/6/22 Eight years ago two witnesses said that police had pressured them to identify Kansas City man Keith Carnes as the shooter in a 2003 killing. But Carnes remained imprisoned. Now that he’s served sixteen years, a judge cited the recantation and prosecutors’ failure to provide a possibly exculpatory informant statement and released Carnes pending retrial. Prosecutors - the same office was involved in the Strickland case (see 11/24/21 update) - say they’re reviewing things.

2/11/22 Veteran Dixmoor (Ill) police officer Jose Villegas faces felony misconduct charges after allegedly telling a witness which photo to select from a lineup. That picture, it turns out, was of an innocent man who walked into a wireless store three days after a robbery and was thought by the witness, an employee, to resemble the suspect. Police responded and arrested Larry Warnsley. In a sense he was lucky, as he only spent 18 days in jail. And yes, he’s suing (click here for the complaint).

11/24/21 Acting on motions filed by Jackson County, Missouri D.A. Jean Baker and the Midwest Innocence Project, a judge exonerated and freed Kevin Strickland, who served more than forty-three years for his alleged involvement in a triple homicide. No physical evidence linked him to the crime, and a survivor who picked him out of a lineup and was the sole basis for his conviction later insisted she had been pressured by police. Strickland’s alibi witnesses were ignored, as were the statements of two confessed participants who swore that he wasn’t there. (See 4/6/22 update)

1/29/20 Twenty-five years after his imprisonment for a gang rape, Rafael Ruiz was exonerated with DNA evidence. He was first tied to the crime through the victim’s erroneous identification of the apartment where her assailants lived. She then identified him through a sloppy show-up process even though his ethnicity didn’t match. His accuser admitted that she had been uncertain but felt “pressured” by police to make an identification.

12/4/19 Thirty-six years after their imprisonment, Alfred Chestnut, Ransom Watkins and Andrew Stewart walked out of prison, once again free men. That’s how long it took before the Baltimore D.A. acknowledged that police and prosecutorial misconduct, including hiding exculpatory evidence and coercing young witnesses, led to their wrongful conviction in the murder of another teen. Authorities think they know who the real killer was, but he died years ago. (See 10/23/23 update)

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Wrong Place, Wrong Time, Wrong Cop Judicial Detachment: Myth or Reality? In Two Fell Swoops

Damn the Evidence - Full Speed Ahead! Want Happy Endings? Don’t Chase Explaining...or Ignoring?

When Should Cops Lie? A Victim of Circumstance Fewer Can Be Better Why do Cops Lie?

Accidentally on Purpose Ideology Trumps Reason Is a Case Ever Too Cold?

Better Late Than Never (II) State of the Art…Not! Rush to Judgment II What if There’s No DNA?

Forensics Under the Gun CSI They’re Not The Usual Suspects Your Lying Eyes

|